If I could teleport myself to any moment in American literary history, I would set my controls for the crisp fall day in November 1856 when Henry David Thoreau met Walt Whitman at Whitman’s family home a few blocks from the Brooklyn Naval Yard. The year before, Whitman had published the first edition of Leaves of Grass, and sent a copy to Thoreau’s mentor, the essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson responded with a glowing fan letter, saying, “I greet you at the beginning of a great career.” Whitman, being Whitman, slapped the great man’s words on the spine of the second edition of his poems, simultaneously pissing off the Sage of Concord and pioneering the book blurb.

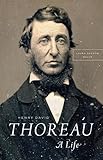

This was the context of Thoreau’s meeting with Whitman on November 10, 1856. As we learn in Laura Dassow Walls’s excellent new biography Henry David Thoreau: A Life, when Thoreau was in his early 20s, Emerson had anointed him as the next great American poet, showering Thoreau with praise and helping him get his poems published. Now 39, Thoreau had long ago given up poetry for essays, but he wanted to meet Emerson’s latest enthusiasm for himself.

This was the context of Thoreau’s meeting with Whitman on November 10, 1856. As we learn in Laura Dassow Walls’s excellent new biography Henry David Thoreau: A Life, when Thoreau was in his early 20s, Emerson had anointed him as the next great American poet, showering Thoreau with praise and helping him get his poems published. Now 39, Thoreau had long ago given up poetry for essays, but he wanted to meet Emerson’s latest enthusiasm for himself.

Things got off to a rough start when Whitman declared, in his casually messianic way, that he represented America and Thoreau responded that he “did not think much of America or of politics & so on—which may have been somewhat of a damper to him.” Thoreau also was put off by the fact that Whitman hadn’t made his bed and left the chamber pot out for all to see. But when Whitman gave Thoreau a copy of his second edition—the one with Emerson’s blurb on the spine—Thoreau loved it, though he was troubled by its sensuality. “He does not celebrate love at all,” he wrote. “It is as if the beasts spoke.”

Things got off to a rough start when Whitman declared, in his casually messianic way, that he represented America and Thoreau responded that he “did not think much of America or of politics & so on—which may have been somewhat of a damper to him.” Thoreau also was put off by the fact that Whitman hadn’t made his bed and left the chamber pot out for all to see. But when Whitman gave Thoreau a copy of his second edition—the one with Emerson’s blurb on the spine—Thoreau loved it, though he was troubled by its sensuality. “He does not celebrate love at all,” he wrote. “It is as if the beasts spoke.”

It is a testament to the power of Walls’s biography, which is on a fast track to definitive status, that she pushes the reader look beyond the obvious Puritan squeamishness of this observation to see how, for a man like Thoreau, who spent his happiest hours tramping in the woods feeding his hunger for contact with raw nature, a poet’s ability to channel the beasts of the field could also be seen as a rare gift.

But the connection between the two men went deeper than that. Whitman was lusty and brash where Thoreau was solitary and contemplative, but in many ways they had led similar lives. Both threw over conventional careers, Whitman as a newspaper editor, Thoreau as a Harvard-educated school teacher, to focus on their writing, much of which they ended up publishing themselves. More than anything, though, they were alike in their indifference to their differentness. Whitman, bohemian and essentially jobless, spent whole days riding the omnibus up and down Broadway declaiming Homer at the top of his lungs. Thoreau had lived for two years in a house he built himself near Walden Pond where he wrote essays, planted beans, and spent weeks in the dead of winter obsessively measuring the pond’s width, length, and depth.

So it’s hardly surprising that when he returned home from his visit to Brooklyn, Thoreau carried his copy of Leaves of Grass, in Emerson’s words, “like a red flag, defiantly.” Thoreau heard in Whitman’s poetry what he was striving to capture in his own work: a true, unadorned American voice. “Though rude & sometimes ineffectual,” he wrote of Whitman’s book, “it is a great primitive poem—an alarum or trumpet-note ringing through the American camp.”

It is a commonplace of writing workshops that writers must first “find their voice,” but today’s writers have it easy, needing only to find a voice authentic to themselves as individuals. The task was trickier for American writers of Thoreau and Whitman’s generation, who came of age in the early 19th century. Writers of the so-called American Renaissance of the 1850s, which include Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman, along with Herman Melville, and Nathaniel Hawthorne, had to locate within themselves a voice authentic not only to them personally, but to an entire nation.

For writers like Thoreau and Whitman, both born in the 1810s, the American Revolution was very much a part of living memory. But while their grandfathers had helped overthrow British tyranny, the literary world they inherited still saw British and European literature as the model for all but the most frivolous popular writing. You can hear this influence in even the work of that most distinctly American author, Edgar Allan Poe, who set many of his most famous tales in Europe, and in his poems employed a rhyme scheme and classical rhetoric (“Quoth the Raven,” etc.) wholly foreign to the American ear.

In his 1844 essay “The Poet,” Emerson called on American writers to cast off shopworn tropes of the past and strive to capture the spirit of their raw, still-forming nation.

Our logrolling, our stumps and their politics, our fisheries, our Negroes, and Indians, our boats, and our repudiations, the wrath of rogues, and the pusillanimity of honest men, the northern trade, the southern planting, the western clearing, Oregon, and Texas, are yet unsung. Yet America is a poem in our eyes; its ample geography dazzles the imagination, and it will not wait long for metres.

Whitman heard a version of this essay as a lecture in Brooklyn, and Leaves of Grass was in many ways an answer to Emerson’s call. But so, too, was Thoreau’s Walden and Melville’s sea tales and Hawthorne’s Puritan-era romances and Emily Dickinson’s verses.

Whitman heard a version of this essay as a lecture in Brooklyn, and Leaves of Grass was in many ways an answer to Emerson’s call. But so, too, was Thoreau’s Walden and Melville’s sea tales and Hawthorne’s Puritan-era romances and Emily Dickinson’s verses.

To an uncanny degree, each of these foundational American writers followed a similar path, stepping off the conventional career track early in their lives to draw inward and look more directly at the world. Whitman quit newspaper work and spent years bumming around New York, taking odd jobs and declaiming poetry on city buses. Melville put out to sea and lived among the natives of the Marquesas Islands. Hawthorne spent 12 reclusive years in his parents’ home studying colonial history and writing fiction. Dickinson, who came along a few years later, retreated into her parents’ home, where she spent much of the next four decades scribbling poems on scraps of paper. And of course, Thoreau built a cabin in the woods near Walden Pond with enough room for a bed and a desk and three chairs—“one for solitude, two for friendship, and three for society.”

One of the pleasures of Walls’s Thoreau is seeing how Thoreau’s stubborn refusal to lead an ordinary life turned a bright but otherwise rather ordinary young man into a great and original artist. The story of Thoreau quitting his first teaching job because he wouldn’t strike his students is the stuff of legend. Less well known is his long, largely unsuccessful struggle to carve out a more conventional career as a writer. For a time, Thoreau wrote poetry while helping out in his family’s pencil business and, later, launching a small private school with his brother John. When that school folded, Thoreau moved to Staten Island where he tutored the son of Emerson’s brother and tried to break into the bustling New York literary market.

Thoreau’s year and a half in Staten Island, the longest he ever lived away from Concord after college, was a slow-moving disaster. “I have not set my traps, yet, but I am getting the bait ready,” he wrote home in a letter shortly after he arrived in New York. But just four months later, he had to admit that “my bait will not tempt the rats; they are too well fed.” To Emerson, he joked ruefully, “Only the Ladies Companion pays…but I could not write anything companionable.”

This was the Thoreau who went into the woods, a 20-something Harvard grad who had tried teaching, tutoring, tinkering, and freelance writing, and ended up back where he began, in his hometown helping out in his parents’ pencil business. But he wasn’t a failure, exactly. By the time he moved to Walden Pond, on July 4, 1845, he had gathered an impressive array of literary benefactors, including Emerson, Hawthorne, and Horace Greeley, the founder and editor of the New-York Tribune, who served as an informal literary agent for Thoreau the rest of his life.

Perhaps more importantly, Thoreau had hit on a successful working method. It began with daily immersion in nature, mostly through walking, which Thoreau did the way other people read the news, and with much the same purpose. He walked everywhere, and everywhere he walked he noticed: What wildflowers were out? On what date had the pond iced over? Why was it that when a farmer cut down a pine forest oak saplings sprouted, but when an oak forest was cut down pine saplings sprung up?

He recorded these observations and questions in his journal, which he had started, at Emerson’s urging, shortly after he finished college and continued until he could literally no longer hold a pen, amassing some two million words. He shaped this raw material into essays, which he tested out in lectures he delivered to his neighbors in Concord as well as to audiences across New England. The best of these lectures he reshaped yet again into articles or book chapters, which he then published.

The cabin at Walden was crucial to all this, putting him in close, daily contact with his principal subject—nature—while giving him a rent-free “room of his own” where he could transform the raw data of his journal entries into lectures and essays, and, after yet another round of sifting and shaping, into books. At the same time, as Walls puts it, Thoreau’s “two years, two months, and two days living at Walden Pond became and would forever remain an iconic work of performance art”—one which, when boiled down to a single, lightly fictionalized year, gave him the narrative spine for his most famous book.

In his short time at the pond, Walls notes, Thoreau began work on the great bulk of the material he is famous for today, including a first draft of his first book, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, a nearly finished draft of Walden, and a rough draft of his essay “Ktaadn,” about his first visit to Mt. Ktaadn, which would figure in his posthumously published book The Maine Woods. The flailing young New York freelancer who couldn’t dream up anything companionable enough for The Lady’s Companion had found his voice.

In his short time at the pond, Walls notes, Thoreau began work on the great bulk of the material he is famous for today, including a first draft of his first book, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, a nearly finished draft of Walden, and a rough draft of his essay “Ktaadn,” about his first visit to Mt. Ktaadn, which would figure in his posthumously published book The Maine Woods. The flailing young New York freelancer who couldn’t dream up anything companionable enough for The Lady’s Companion had found his voice.

That voice, by turns cocky and self-serious, erudite and homespun, spiritual and blasphemous, rings out from every page of Walden: “The mass of men live lives of quiet desperation.” “I would rather sit on a pumpkin and have it all to myself, than be crowded on a velvet cushion.” “Sell your clothes and keep your thoughts.”

It’s there, too, in Whitman’s “Song of Myself”—“I cock my hat as I please indoors or out”—and in the iconic opening line of Melville’s Moby-Dick: “Call me Ishmael.” From there, the American sound changed and grew as the country itself grew. The writers of this first American Renaissance were all white men from the Northeast. As the nation spread westward, writers like Mark Twain and Ambrose Bierce added a tart dose of western humor to American literature and Southern writers like William Faulkner pulled and stretched the English language like taffy. Women writers like Edith Wharton and Willa Cather joined the choir, as did black writers of the Harlem Renaissance like Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes.

It’s there, too, in Whitman’s “Song of Myself”—“I cock my hat as I please indoors or out”—and in the iconic opening line of Melville’s Moby-Dick: “Call me Ishmael.” From there, the American sound changed and grew as the country itself grew. The writers of this first American Renaissance were all white men from the Northeast. As the nation spread westward, writers like Mark Twain and Ambrose Bierce added a tart dose of western humor to American literature and Southern writers like William Faulkner pulled and stretched the English language like taffy. Women writers like Edith Wharton and Willa Cather joined the choir, as did black writers of the Harlem Renaissance like Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes.

Each generation since — the great Jewish novelists of the 1950s, the Black Arts Movement poets of the 1960s, the Dirty Realists of the 1980s — has shaped and refined how America sounds to the world, but that distinctly American voice, now so familiar we only hear it when a writer finds a new way to use it, can be traced directly back to Thoreau and Whitman and the other writers of the 1850s, who broke away from their European influences and created a truly American literature. What’s interesting is how they found it. The writers of the American Renaissance were extraordinarily well-read, but they arrived at their unique sound not principally through reading, but through deep immersion in the world. To one degree or another, they each stopped what they were doing and listened, and what they heard coming back was the sound of a new country.

Image Credit: Pexels/Mihis Alex.