1.

[Warning: Spoilers ahead.]

The final episode of Hulu’s television adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale—like the rest of the show—is far more suspenseful than the original 1985 novel written by Margaret Atwood. Hulu’s Offred engages in several radically defiant acts; you worry more for her safety than you did in the book. But while these additions to plot probably make for better viewing, they obscure the central brilliance of the novel, which took its power from the mundane horrors of the handmaid Offred’s everyday life.

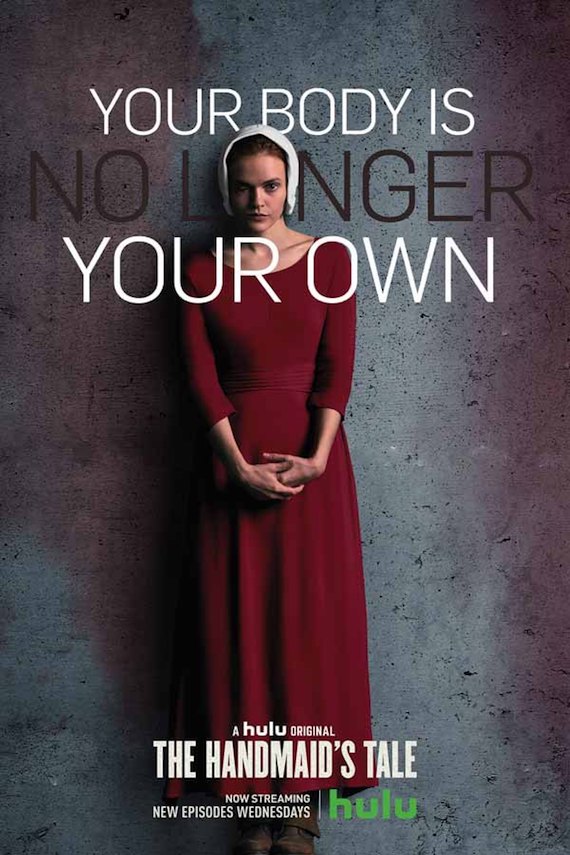

In the show, a subversive handmaid tells Offred to pick up a special package for safekeeping. After she obtains the parcel, Offred marches home proudly. “They should’ve never given us uniforms if they didn’t want us to be an army,” she says of the state-mandated red garb she must wear. Offred, like her fellow handmaids, is forced to undergo a ritualized rape so that she can bear children for the well-to-do men of a totalitarian state. To endure this servitude, Hulu’s Offred finds solace in small acts of resistance.

In the show, a subversive handmaid tells Offred to pick up a special package for safekeeping. After she obtains the parcel, Offred marches home proudly. “They should’ve never given us uniforms if they didn’t want us to be an army,” she says of the state-mandated red garb she must wear. Offred, like her fellow handmaids, is forced to undergo a ritualized rape so that she can bear children for the well-to-do men of a totalitarian state. To endure this servitude, Hulu’s Offred finds solace in small acts of resistance.

But the original Offred, Atwood’s intended Offred, is far less politically active. In the novel, Offred recalls her feminist mother, whose activist leanings she always had trouble relating to. Even the regime of Gilead does not radicalize her; indeed, she is outwardly compliant—she attempts to get pregnant from a tryst with her assigned commander’s driver, at the suggestion of her mistress, his wife, Serena Joy.

The show, however, features Girl Power Moments set to danceable tunes. One of these intrusive songs is the otherwise wonderful Nina Simone’s “Feeling Good.” It plays when, having stood up to the insidious Aunt Lydia, Offred and her fellow handmaids march down a wintry street, Offred leading the red cloaked women. Hulu’s Offred takes strong political stances against the regime under which she suffers. This, of course, is not worthy of recrimination—there is much to admire about her character. But her political bent makes her more unique, more of a leader than an Everywoman.

While transforming Offred into a stereotypically empowered representation of a woman may make the show more appealing to some viewers, I found it disheartening. To me, the book drew its magic from Offred’s stance as a witness. Not everyone is able to act in open defiance when the stakes are truly life and death, nor should people in unjust situations be blamed for their inability to escape them. The book offered another option for the oppressed; Atwood’s Offred finds, to steal a phrase from the French philosopher Hélène Cixous, “a way out” through the simple act of telling her own story.

2.

Offred’s narration, though fiction, falls within a long tradition, as first-person narratives of life in bondage date back to colonial times. In the late 17th century, Mary Rowlandson wrote one of the first so-called captivity narratives about her experience as a hostage of Native Americans. The book, which was immensely popular at the time, has a didactic, moralizing quality. Rowlandson tells her story and at the end determines that her time in captivity was God’s punishment for the selfishness she indulged in prior to being kidnapped.

While the bondage narratives of the 17th and 18th centuries were predominantly written by and about white Americans, the bondage narratives of the 19th century were mostly written by and about black people who had been enslaved. The former category, that of captivity narratives, was largely about enforcing racist stereotypes that helped justify colonists’ mistreatment of Native Americans. The latter category, on the other hand, generally worked to tell individual stories, with the aim of aiding the abolitionist cause. The audience for both was almost always educated white readers.

Oddly, given the problematic racial politics of the The Handmaid’s Tale, both book and show, the narration of Atwood’s Offred has much in common with 19th-century slave narratives. As with famous examples like Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave, the textual version of The Handmaid’s Tale makes its potent political statement through the act of recounting what daily life was like, rather than through more explicit political commentary. “I have no comments to make upon the subject of Slavery,” wrote Northup at the end of his story. “Those who read this book may form their own opinions of the ‘peculiar institution.’ This is no fiction, no exaggeration.”

Oddly, given the problematic racial politics of the The Handmaid’s Tale, both book and show, the narration of Atwood’s Offred has much in common with 19th-century slave narratives. As with famous examples like Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave, the textual version of The Handmaid’s Tale makes its potent political statement through the act of recounting what daily life was like, rather than through more explicit political commentary. “I have no comments to make upon the subject of Slavery,” wrote Northup at the end of his story. “Those who read this book may form their own opinions of the ‘peculiar institution.’ This is no fiction, no exaggeration.”

The process of mapping a fictional sex-based oppression narrative onto the historical trope of race-based slavery yielded imperfect results in both the novel and show. The book’s aracial approach—minorities have been rounded up and sent to the so-called “colonies,” is particularly troubling, especially when the novel uses a historically black narrative format. The Hulu show, on the other hand, as Angelica Jade Bastién writes, features a somewhat glib “post-racial” approach. Minorities haven’t been sent to the colonies and are featured as prominent characters (Offred’s husband, daughter, and best friend), but the show fails to realistically address how race would function in an American religious authoritarian regime like that of Gilead.

3.

That Atwood’s novel is a futuristic bondage narrative becomes overwhelmingly evident in the final pages of the book, which come in the form of an appended “Historical Note.” Offred’s narration ends mysteriously with her being taken away from Commander Waterford’s house in a van. The epilogue is set at a University of Nunavit conference set in 2195, many years after the collapse of Gilead.

A professor named Piexoto gives a talk on “The Handmaid’s Tale,” which has been discovered in the form of 30 tape cassettes in a footlocker. In this metafictional moment that departs from the confessional realist style that dominates the novel, Piexoto discusses scholars’ intense examination of the tapes in order to verify their accuracy and determine the speaker’s identity—a pursuit which ends in frustration. He reveals that he believes they were made after the fact while the narrator hid in a house along the Underground Femaleroad as she attempted to escape Gilead. His speech’s opening reveals a good deal about the society that has replaced Gilead:

This item—I hesitate to use the word document—was unearthed on the site of what was once the city of Bangor, in what at the time prior to the inception of the Gileadean regime, would have been the state of Maine. We know that this city was a prominent way station on …the ‘Underground Femaleroad,’ since dubbed by some of our historical wags ‘The Underground Frailroad.’ (Laughter, groans.) For this reason, our association has taken a particular interest in it.

Piexoto questions the legitimacy of Offred’s narrative, reluctant to call it a document but rather demoting it to the rank of “item.” Furthermore, Piexoto’s insensitive crack about the “The Underground Frailroad” is only made worse by the fact that he has just read a narrative detailing the horrors of gender oppression and has gained little from it. It is this bleak ending that suggests the limits of storytelling and the bondage narrative: unlike with activism, or even a more active text like the Hulu show, the apolitical bondage narrative does not imbue every reader with a more progressive set of politics; the interpretation of any personal narrative is subject to the whims of readers the narrative’s creator never chose.

In the final episode of Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale, Offred opens the secret package she was told to keep safe and finds writings by women who have also been enslaved as handmaids. She is overjoyed by reading the accounts of other women in similar situations. She falls asleep reading these accounts, and the next day she, as previously mentioned, refuses Aunt Lydia’s mandate that she and her fellow handmaids stone another handmaid to death. It’s a somewhat clunky plot mechanism for generating Offred’s inspiration, but it seems to be the closest the final episode of the Hulu adaptation comes to making a nod to the narrative origins of the story.

4.

Though the novel’s “Historical Note” undoes the explicit political force of Offred’s narration, the book—somehow, incredibly—affirms a farther-reaching and perhaps even more important message. Because if you can’t change the world you live in, you can find your way out of it. Hélène Cixous wrote that women writing their own stories was a way to escape patriarchal society. In a 1975 essay called “Sorties / Out and Out / Attacks, Ways Out and Forays,” Cixous writes that self-expression could help women combat their oppression. “It is writing in writing, from woman and toward woman, and in accepting the challenge of the discourse controlled by the phallus, that woman will affirm woman somewhere other than in silence.”

Breaking one’s silence, if oppressed as Offred is, is a vital means for survival. In both the show and the novel, handmaids like Offred are forced to be obedient. “Blessed are the meek,” Aunt Lydia tells them. Eyes down and hands folded, she tells the woman—whom she calls “girls”—when they first, after being captured, enter the handmaid training center. Then later, when they are out in public, they avert their eyes and wear absurdly modest bonnets that cover most of their faces. Its visuals like this that remind me of a line from Cixous’s essay: “Is this me, this no-body that is dressed up, wrapped in veils, carefully kept distant, pushed to the side of History and change, nullified, kept out of the way, on the edge of the stage, on the kitchenside, the bedside?”

At the end of the novel, though her story is co-opted by an insensitive historian, the answer to Cixous’s question for Atwood’s Offred, having spoken her truth, is most certainly, no. As for how the Hulu adaptation would answer that same question, I think the answer is more complicated, as Hulu’s Offred has shown herself to be a more actively resistant heroine. Perhaps she won’t be recorded in history in the same way Atwood’s, but in the end, both representations show women who are doing what they need to survive—and that’s what matters most.