1. Joseles’s Song

Yo canto historias

De nuestros cuerpos

Durmiendo en la luna

Que nunca se olvida…… no me dejes solo

como un pajarito

enamorado con aire

pero sin sus alas

My friend Joseles died last summer. He went missing near Palm Springs in mid-June, and turned up behind a strip mall there in July. An off-leash dog found his body. A lot still isn’t clear about how Joseles landed naked in an alley, but what does seem clear now is that he’d been partying at a nearby gay resort, or boys’ club. Since I embrace the utopian potential of spaces like the bathhouse, I felt an especially pressing need to understand the tragedy, its causes and implications.

Joseles and I became friends in college. We belonged to the student labor coalition, formed a protest affinity group for direct actions, and played in a feminist punk band on campus, Joseles on guitar and myself on bass. In San Francisco, where Joseles worked for a low-income housing clinic and I for a service workers’ union, our crew made up the membership of Pride at Work, a queer-oriented team of activists for economic justice. We still played music sometimes; I kept my bass amp at the home Joseles shared with a handful of our friends, where he wrote the song above. While I lived in a collective nearby, Joseles’s housemates went further: they combined all their possessions and organized the place accordingly, right down to communal beds and lubricant.

Our circle from the Bay dispersed; I left years ago, and others followed. It felt impossibly surreal to see everyone again outside the church, dressed in black in the desert heat. I spent time with my old friend Diego, reconnecting and piecing together Joseles’s final months. I learned that Joseles had been ill, jobless, and essentially homeless. His boyfriend had kicked him out, after which he had couch-surfed until moving back in with his mom there, in Cathedral City. He’d begun to pursue teaching credentials before he disappeared.

Meth spread through gay party culture not long after effective HIV medication; apparently Joseles started slamming up north. His last boyfriend came down for the funeral, and learned from someone at the boys’ club that Joseles had been there the weekend he vanished. His host at the club claims to have dropped him off at a bus stop after a weekend of partying, but he also claims not to know about the drugs on which the coroner eventually blamed Joseles’s death. I’m angry that the police and even a private detective stopped short of determining how his body ended up behind a furniture store. News reports kept repeating that he “was using gay dating app Grindr,” as if to say, “but of course.”

Even without knowing exactly what happened, my greatest anguish was the idea that we as a community failed Joseles. And it was worse because to an extent, I understand what he might have gone through. My work in San Francisco had already placed enormous stress on my body and mind, but within nine months of leaving for a new, related assignment, I’d landed in a hospital myself. I only told a few people what I was dealing with, none of them from our circle back in the Bay. And it wasn’t just me. Diego told me he had also endured a mental health crisis, sometime between mine and Joseles’s. The three of us thrashed about in different directions; Diego bounced back more quickly than I did, but I can imagine how Joseles didn’t manage. I found myself wishing that even if we couldn’t all have stuck together, we could more easily have plugged into other communal structures that would have seen us through.

In a twist Joseles would’ve loved, our friend’s small dog shat all over the church floor, at which point the whole pew of us had to stop crying. Now his online presence consists mostly of death records, but for a while one could still see traces of his life: fundraising in drag, advising Tenderloin tenants, identifying as a “border Xer.” And there’s this, which he pinned on the Christian Left Facebook page a few years back, expressing an ideal of bodily and spiritual integration:

When you make the two one, and when you make the inside like the outside and the outside like the inside, and the above like the below and the below like the above, and when you make the male like the female and the female like the male, then you will enter the Kingdom. — Jesus in the Gnostic Gospel of Thomas

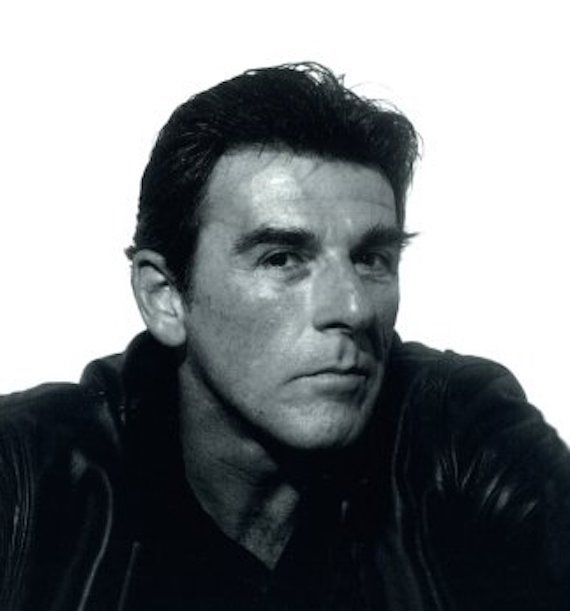

2. Thom’s Verse

In a disturbing coincidence, Joseles’s death echoed that of fellow Stanford poet Thom Gunn. Gunn too died using meth and was left by an unknown witness, likely a lover. Joseles and I were in college then, but Gunn, 72 when he died, had a penchant for exactly the type my friend would become: unemployed and semi-homeless, with a habit. Yet those supplying Joseles were likely Gunn’s own sort: successful, white, and older. Gunn’s final book, Boss Cupid, includes a handful of poems on seduction and speed with young partners. In “Front Door Man,” he asks Cupid about one such visitor, “Are you appointing me/ To hold him safe tonight/ Or use him for my delight?” Gunn died in his own room, unnoticed by his housemates until later in the day.

In a disturbing coincidence, Joseles’s death echoed that of fellow Stanford poet Thom Gunn. Gunn too died using meth and was left by an unknown witness, likely a lover. Joseles and I were in college then, but Gunn, 72 when he died, had a penchant for exactly the type my friend would become: unemployed and semi-homeless, with a habit. Yet those supplying Joseles were likely Gunn’s own sort: successful, white, and older. Gunn’s final book, Boss Cupid, includes a handful of poems on seduction and speed with young partners. In “Front Door Man,” he asks Cupid about one such visitor, “Are you appointing me/ To hold him safe tonight/ Or use him for my delight?” Gunn died in his own room, unnoticed by his housemates until later in the day.

Gunn and his partner, Mike Kitay, met at Cambridge. Gunn came west for Kitay’s military service, and to Stanford for an M.F.A. in 1954. He joined the Berkeley faculty in 1958, but gave up tenure there in the ‘60s to escape department meetings. Starting in 1971, Gunn and Kitay lived in the Haight on Cole Street, sharing a house with lovers and friends. Until Gunn died, and later Kitay, residents faithfully adhered to a schedule of designated cooking nights, eating together each evening. Edmund White considered them “commune dwellers,” and poet August Kleinzahler called it “an unusually stable domestic situation by any standards.” In his 1992 book The Man with Night Sweats, Gunn depicts that sense of tight-knit community as expanding well beyond his home:

Gunn and his partner, Mike Kitay, met at Cambridge. Gunn came west for Kitay’s military service, and to Stanford for an M.F.A. in 1954. He joined the Berkeley faculty in 1958, but gave up tenure there in the ‘60s to escape department meetings. Starting in 1971, Gunn and Kitay lived in the Haight on Cole Street, sharing a house with lovers and friends. Until Gunn died, and later Kitay, residents faithfully adhered to a schedule of designated cooking nights, eating together each evening. Edmund White considered them “commune dwellers,” and poet August Kleinzahler called it “an unusually stable domestic situation by any standards.” In his 1992 book The Man with Night Sweats, Gunn depicts that sense of tight-knit community as expanding well beyond his home:

The warmth investing me

Led outward through mind, limb, feeling, and more

In an involved increasing family.Contact of friend led to another friend,

Supple entwinement through the living mass

Which for all that I knew might have no end,

Image of an unlimited embrace.

Gunn uses the past tense because as in many of the book’s poems, he goes on to mourn the ravages of AIDS. While the literary world had often dismissed his earlier volumes on gay life in San Francisco, this one was a hit. But following it with Boss Cupid, Gunn reminds his readers that the entwined limbs’ embrace was an unapologetically erotic one. In “Saturday Night,” he laments the passing of that age, when bathhouses represented a “community of the carnal heart.” He writes of that time,

If, furthermore,

Our Dionysian experiment

To build a city never dared before

Dies without reaching to its full extent,

At least in the endeavor we translate

Our common ecstasy to a brief ascent

Of the complete, grasped, paradisal state

Against the wisdom pointing us away.

3. A City Never Dared Before

Gunn lived much of his life by the principle of free love: a deliberate transcendence of socially prescribed coupling practices. Communal play settings can be a part of this and often are — but for those of us eschewing the nuclear model, chosen family like Gunn’s is essential.

The concept of free love has an estimable past. Historically it has revolved around rights for women and gays. Many of its advocates have associated marriage in particular with colonial-style social control. Free love (also called sex radicalism in the past) was especially fundamental to communally- and culturally-minded feminists like Mary Wollstonecraft, Natalie Barney, and Lou Andreas-Salomé. All of these women prized both their personal independence and their close ties to lovers and friends. Wollstonecraft and her partner William Godwin lived separately in their shared Polygon home. Expatriate Barney hosted legendary Left Bank salons at the Villa Trait d’Union, a similar conjoined domicile with lesbian partner Romaine Brooks. Andreas-Salome, a pioneering psychoanalyst of women’s sexuality, set out to found the Winterplan commune with Friedrich Nietzsche and Paul Rée while declining to marry either. In her anarchist classic Marriage and Love, Emma Goldman made a passionate case against hegemonic monogamy and the bourgeois family unit. Bolshevik diplomat Alexandra Kollontai promoted free love while founding the Soviet Women’s Department (unsurprisingly, Joseph Stalin put the kibosh on that message).

Leading up to the 1967 “Summer of Love,” the cause gained greater traction. Seeking to cross received boundaries, thinkers, artists, and activists advanced what Michel Foucault called “a different economy of bodies and pleasures.” In the popular narrative of Aquarian-era free love, men abdicated responsibility while women bore the costs of family planning. Certainly this is a constant from Hester Prynne to Billie Jean. But back in the Bay Area, a number of projects more seriously explored different styles of intimacy. One of these was San Francisco’s Kerista group, which practiced a regimented form of communal relationship: four clusters of six or seven people sharing flats in the Haight, rotating partners according to a schedule. Keristans widely publicized ideas we now associate with polyamory. Beyond that, the men obtained vasectomies and received nine-point tutorials on cunnilingus. As a clan they put out comic books, engaged in public “Gestalt-o-Rama” rap sessions, and ran a successful tech business. Another East Bay group has since the ‘70s lived in purple-painted buildings it calls the “MoreHouses.” They held the first public demonstration of a female orgasm, and still host related workshops.

While the gay bathhouse may have entered the public consciousness in the Stonewall period, records in the U.S. date back over 100 years, when the Gershwins managed one such New York facility. The baths grew in popularity over the midcentury — and in the ‘70s, with sites like the Barracks of Gunn’s poem, the BDSM club took root. Fetish art, commercial dungeons, and a gay leather scene had all existed underground. But determined sex radicals like Cynthia Slater brought kink practices into the light, amid scorching controversy within the LGBT and feminist movements. San Francisco’s early gay pride parades banned nascent SM groups like Slater’s, and feminist conferences splintered over the subject of power play. Noted personalities like Foucault and Robert Mapplethorpe patronized the exclusive Mineshaft in New York and pansexual Catacombs in San Francisco. Painfully though, by the time the close community understood HIV well enough to effectively quell its spread, Foucault, Slater and Mapplethorpe had all succumbed.

Apps like Grindr have changed bathhouse culture, moving more action to private venues, while kink is available for mass consumption at San Francisco’s annual Folsom Street Fair. Meanwhile in the ‘90s, all-night discos morphed into circuit party club-crawls, like Folsom’s Dore Alley for men and Palm Springs’s Dinah Shore week for women. In Cape Cod, early artists’ colony Provincetown has become legendary for gay tourism and festivals. The fall Women’s Week, for instance, pitches itself “between a safe haven and a party.”

At the same time, mixed households of polyamorous individuals are dotting major cities’ landscapes. While providing an accepting environment for residents’ relationship choices, complexes like the Bushwick Hacienda function less like cooperatives than adult dorms. Burning Man, or as Joseles called it, “white people act crazy week,” is basically a circuit party with many straight attendees: sex, drugs, and copious spending. He once went with only a shopping cart, making a salient point about the so-called “gift economy.”

Viewed from one angle though, Burners descend from Kerista. The Keristans believed in science, and took up early Apple computers as a way to generate income for the commune. They rented the machines out of a shop they called Utopian Technologies, and soon offered training, support, and repairs. By the late ‘80s the business, then called Abacus, became Northern California’s top Macintosh dealer. The commune shared the profits equally among members, but plenty of Keristans still identified less as techies than hippies. Many removed themselves to more tranquil lives in the redwoods or Hawaii, but some remained in San Francisco and joined other companies. The wider shift to yuppie swinger culture, along with the AIDS epidemic, points toward the state of the scene today: a reorientation of free love from a communal commitment to a transactional experience.

Thom Gunn’s household lived on in the Haight, but other gay libertines found life in the cities too compromising. With family roles a feminist battleground, groups of radical lesbians had moved to rural areas to develop land trusts and invent a shared life. One contingent of gay men followed a similar path, and might hold inspiration for a carnal community future.

4. Entering the Kingdom

Harry Hay was a sailor, stunt-rider, Stanford dropout and Kinsey subject active in the Communist Party. He founded pioneering gay rights group the Mattachine Society in Silver Lake, Los Angeles, in 1950. In 1954 he met his life partner and took on a role in his kaleidoscope business, and in the 1960s they helped start the North American Conference of Homophile Organizations (NACHO). After Stonewall birthed the Gay Liberation Front, Hay chaired its Los Angeles chapter, coordinating events like a “gay-in” at Griffith Park. He and his partner spent the 1970s in New Mexico, where they were involved in gay and indigenous causes. They returned to LA in 1978, and planned a gay retreat to Arizona for the following year. The ashram space they booked there was for 75 men, but three times as many came. Participants found the four days transformative without drugs as Hay urged them to “throw off the ugly green frog-skin of hetero-imitation.” The men studied botany, health and healing practices, and spiritual matters, joining in performance art and erotic rituals, dressed in little but bells and rainbow makeup. They called themselves Radical Faeries.

The next year they convened a group of 400 in Colorado, where they discussed a desire for their own communally held land. An existing leftist collective at Short Mountain in Tennessee had mostly dispersed; the Faeries took to the spot and created a community land trust. The group continues to inhabit the location, and more recent transplants there have found ways to protect the land and care for aging communards. Today, about 20 men live in home-built cabins on site and hold major gatherings twice annually. They have a network of outposts in other states and countries, and a neighborhood of other queer collectives — younger and more diverse — has sprung up around them in middle Tennessee. The Faeries there use solar power, spring water, and wood fires, grow their own food and eat nightly meals together, operating on consensus.

Before I left San Francisco, my fellow radicals and I had talked about eventually creating a settlement where we could provide shelter and fellowship to each other and others. Rather than the countryside, we hoped to set up somewhere more urban, believing that together we could do more for people around us. Soon our lives pointed too many disparate ways; we were in our mid-20s. Maybe that particular group wasn’t designed to last.

Yet life’s crises aren’t all behind any of my friends or me. Most of us will face infirmity of one kind or another, regardless of habits or careers. Those who reject the sequestration of the patriarchal-style family can’t just replicate it individually, where isolation is even more dangerous. Social events and hookup apps might offer chances for play, but without a net of close, caring companions, they can never suffice. We have to carve out communal space for our own ways of living and loving. We might not all share sex toys or go off the grid, but we can save economically and environmentally by aggregating supplies and equipment. We can facilitate exchange of ideas in a way that benefits our wider community, and collaborate on projects without having to run a start-up. We can share aspects of our play without needing to all sleep together, and cultivate honesty free of judgment. We can look out for each other’s health, and if we worry for someone, seek to reduce harm. And if one of us dies in our 70s pursuing a good time, at least we will have made it that far.

We have nothing to lose but our frog-skin.