Antecedents to Munnu: A Boy From Kashmir, Malik Sajad’s graphic novel about the writhing valley of Kashmir are not numerous. Born in 1987 in Srinagar, Sajad spent his formative years in Kashmir at the time of curfews and crackdowns, an experience documented in Munnu. This tumult was the result of the continuing political and cultural crisis that followed Partition, with both Pakistan and India claiming the Kashmir valley and thus dividing its citizens — some claim that Kashmir belongs to one of the two nations, while others demand its independence. This divide, also religious, was recalled by Salman Rushdie in The Paris Review:

When I was probably no older than twelve we went on a family trip to Kashmir…When we got to our rest house my mother discovered that the pony that should have been carrying all the food didn’t have the food on board. She had three fractious children with her, so she sent the pony guy off to the village to see what could be had, and he came back and said, There’s no food, there’s nothing to be had. They don’t have anything. And she said, What do you mean? There can’t be nothing. There must be some eggs — what do you mean nothing? He said, No, there’s nothing. And so she said, Well, we can’t have dinner, nobody’s going to eat. About an hour later we saw this procession of a half-dozen people coming up from the village, bringing food. The village headman came up to us and said, I want to apologise to you, because when we told the guy there wasn’t any food we thought you were a Hindu family. But, he said, when we heard it was a Muslim family we had to bring food. We won’t accept any payment, and we apologise for having been so discourteous.

In Munnu, Sajad negotiates the private identity with the public crisis that has gripped the valley. In the monochromatic tiles and anthropomorphism of Munnu, Sajad is unsettlingly blunt about the brutality of army personnel in Srinagar, doing away with the idealism that mars debates in suburban Indian homes, often shaped by news channels, where sensationalists run amok, and Bollywood, which would rather engage in melodrama and merrymaking, and delegate the realism to its estranged cousin, the Parallel Cinema. Both these media are ridiculed in a single speech balloon.

Comparisons to Art Spiegelman’s Maus are inevitable; in Munnu the Kashmiris, as endangered as their state animal, are drawn as Hangul deer, while their poachers or anyone beyond the valley’s limits, are humans. Spiegelman assigns an anthropomorphic quality to every nationality: the canine Americans, the porcine Poles. Sajad assigns, ironically, anyone not native to the valley a human form; the Hanguls — his mother, father, siblings, neighbors, and mates — are pitted against the Homo Sapiens. The sentimentality in such a choice is difficult to overlook. Sajad remains steadfast in his Hangul identity, never flitting between species.

Comparisons to Art Spiegelman’s Maus are inevitable; in Munnu the Kashmiris, as endangered as their state animal, are drawn as Hangul deer, while their poachers or anyone beyond the valley’s limits, are humans. Spiegelman assigns an anthropomorphic quality to every nationality: the canine Americans, the porcine Poles. Sajad assigns, ironically, anyone not native to the valley a human form; the Hanguls — his mother, father, siblings, neighbors, and mates — are pitted against the Homo Sapiens. The sentimentality in such a choice is difficult to overlook. Sajad remains steadfast in his Hangul identity, never flitting between species.

Munnu bursts forth with the sparkling clarity of a neo-Romantic novelistic autobiography, bringing to mind the chronology of Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. Of course, Sajad’s unique medium of imbibition and narration force a negotiation with oral traditions. The section titled “Footnotes” opens with a glorious collection of panels and it is appropriately titled — smack in the middle of the narration of the boy and his family, Sajad charts the history of the valley, from its folkloric origins involving a terrorizing demon and the monk who engorged himself to become the valley and displace a dragon, to the Indian Army landing in Kashmir on October 27, 1947, the drawing of the so-called Line of Control between India and Pakistan., and the intra-wars of the militant groups. It is not as much of an afterthought as an addendum.

Munnu bursts forth with the sparkling clarity of a neo-Romantic novelistic autobiography, bringing to mind the chronology of Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. Of course, Sajad’s unique medium of imbibition and narration force a negotiation with oral traditions. The section titled “Footnotes” opens with a glorious collection of panels and it is appropriately titled — smack in the middle of the narration of the boy and his family, Sajad charts the history of the valley, from its folkloric origins involving a terrorizing demon and the monk who engorged himself to become the valley and displace a dragon, to the Indian Army landing in Kashmir on October 27, 1947, the drawing of the so-called Line of Control between India and Pakistan., and the intra-wars of the militant groups. It is not as much of an afterthought as an addendum.

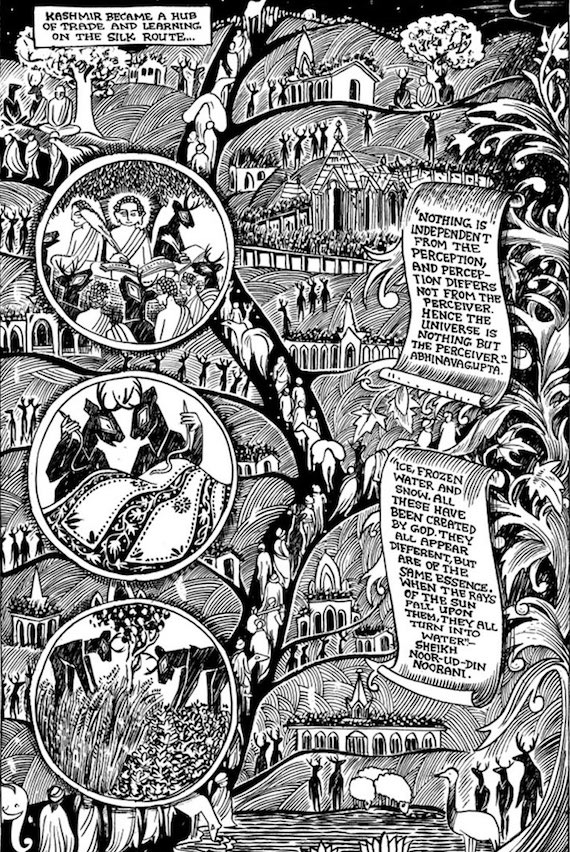

Whilst Spiegelman’s “Prisoners on the Hell Planet” adds an after-aftereffect to the mass incarceration ordered by the Führer, “Footnotes” is more of a succinct recapitulation of the treatment of Hanguls by the various waves of visitors to the valley. The prosperity of the valley as it thrived upon the Silk Route is on full display on the left supplemented by words from Abhinavagupta and Sheikh Noor-ud-din Noorani.

On the right, the famous declaration of love by Amir Khusrau is cruelly borrowed first by the Mughals, then the Afghans, and then the Sikhs. “If there is a Paradise on Earth” paints the invaders in the guise of marauders as they are perched gloriously upon their horses while at their feet lie the Hanguls, first in their military garb, then their arrow-pierced corpses, then with their skulls and ribs laid bare. The decomposition is complete with each “It is here,” reminding one of Walt Whitman’s “heart, heart, heart” that imitates, gloriously, audibly, the “bleeding drops of red.”

The nuanced bildungsroman that is Munnu, the steady metamorphosis of the naive primary schoolchild to the blood-boiling political cartoonist, employed in his adolescence, is some distant cousin of Marjane Satrapi’s Marji in Persepolis. United by their experiences, both play a daily game of hopscotch with armed personnel which is an early entry into disenchantment with their lands: as a rectification for his physical abuse, Munnu’s father takes him on a tour of the old city on his bicycle while the conclusion of the novel contains a shady episode involving two men and a woman in a guarded auto rickshaw. An adjustment to curfews and crackdowns — to avoid being whisked away by armed men, at least — is the plight of the Spiegelmans, the Satrapis, and Munnu’s family. However it would be elementary to homogenize their experiences, just as it is elementary to conflate together the experiences of the North-East Indian states, Kashmir with Assam or Nagaland (the Naga experience, specifically, documented by Temsula Ao in These Hills Called Home and Laburnum for My Head).

The tools Sajad uses to contain his experiences into tiles is inspired partly by observing his father who etched patterns into wood and metal. Whilst Spiegelman conforms with an inky aesthetic with a consistent cross-hatching, and Satrapi a monolithic chiaroscuro, it seems that individual lines never crossing paths might as well have been a recreation of the texture of un-veneered wood. The Hanguls are as angular as matchsticks or the faces Munnu carves into pieces of chalk and fashions out of nibs of pencils to impress his schoolmates. The melting frames of the humans might as well be a Munch-ian nod or an homage to “Prisoners on the Hell Planet.” Sajad is acutely aware of the history of the genre: in the text he fawns over Joe Sacco’s fine hair detail, a DVD of Ivan’s Childhood is fodder for empathy, and R.K. Laxman’s Common Man is out of place and out of character in a fateful Delhi cyber café. Although the Laxman jab might have been a little foolhardy, Sajad has produced a probing visual memoir that translates anger and shame, perhaps incites it, too. More importantly, it delights with its recklessness; the strokes, sometimes practiced like an established language system as rich as Urdu, sometimes unshackled, flip the bird to censors.

The tools Sajad uses to contain his experiences into tiles is inspired partly by observing his father who etched patterns into wood and metal. Whilst Spiegelman conforms with an inky aesthetic with a consistent cross-hatching, and Satrapi a monolithic chiaroscuro, it seems that individual lines never crossing paths might as well have been a recreation of the texture of un-veneered wood. The Hanguls are as angular as matchsticks or the faces Munnu carves into pieces of chalk and fashions out of nibs of pencils to impress his schoolmates. The melting frames of the humans might as well be a Munch-ian nod or an homage to “Prisoners on the Hell Planet.” Sajad is acutely aware of the history of the genre: in the text he fawns over Joe Sacco’s fine hair detail, a DVD of Ivan’s Childhood is fodder for empathy, and R.K. Laxman’s Common Man is out of place and out of character in a fateful Delhi cyber café. Although the Laxman jab might have been a little foolhardy, Sajad has produced a probing visual memoir that translates anger and shame, perhaps incites it, too. More importantly, it delights with its recklessness; the strokes, sometimes practiced like an established language system as rich as Urdu, sometimes unshackled, flip the bird to censors.

Ismat Chughtai’s 1942 story “Lihaaf” challenged heteronormative relations and landed its author in court. There was the fatwa against Salman Rushdie. Arundhati Roy too is a guest at the party. It is noteworthy that all this subjugation is for pieces of what we call fiction. Munnu is a revelatory testimony, resplendent with observation and direct, uninhibited interrogation of a state that makes Munnu a citizen of war who cannot meekly submit and cannot wildly revolt and must therefore compromise for a state somewhere in-between, a state that has characterized his own nation.