Constraints in writing have a way of helpfully containing possibilities. Speaking to the role of constraints in poetry, Anne Sexton once said, “You could let some extraordinary animals out if you had the right cage.” Take the sonnet, a strict poetic form that consists of 14 lines of iambic pentameter that has endured for more than seven centuries. Take Pale Fire, which presents itself as an explication of a single poem, yet digressively explicates an entire life. Or, take Green Eggs and Ham, which Dr. Seuss wrote after his editor challenged him to create a book using no more than 50 different words.

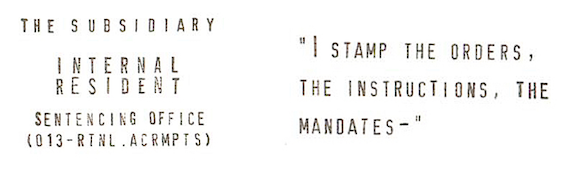

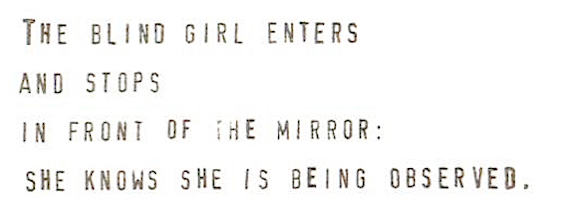

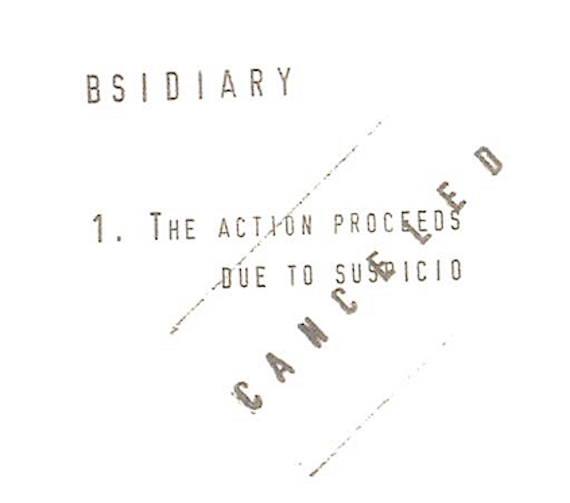

One of the major constraints of Matías Celedón’s The Subsidiary is a technical one. He wrote this book with a now discontinued stamp set called a Trodat 4253 that he found at an office supply sale. The device allows one to arrange characters on a stamp any way he likes, but limits the output to the size of the stamp. The result feels as much like an art exhibit, as it does a novel. Most of the 200 pages in the book are constrained to less than five lines of text, and fewer than 90 characters. This is a book that can be read as fast as the reader can turn the page, and that momentum elevates the unsettling effect of the nightmare.

One of the major constraints of Matías Celedón’s The Subsidiary is a technical one. He wrote this book with a now discontinued stamp set called a Trodat 4253 that he found at an office supply sale. The device allows one to arrange characters on a stamp any way he likes, but limits the output to the size of the stamp. The result feels as much like an art exhibit, as it does a novel. Most of the 200 pages in the book are constrained to less than five lines of text, and fewer than 90 characters. This is a book that can be read as fast as the reader can turn the page, and that momentum elevates the unsettling effect of the nightmare.

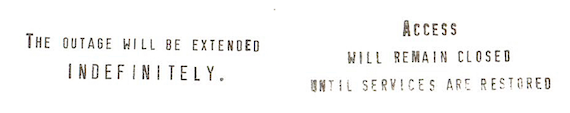

The Subsidiary tells the story of a worker trapped in the offices of a Latin American corporation, who uses the materials at his desk to give testimony of his experience. The book begins with a loudspeaker announcement that the power supply will be interrupted between 8:30 and 20:00. The exits are closed off. The phone lines go down. There’s shouting outside.

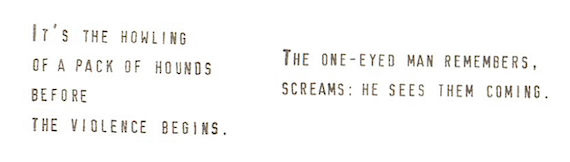

The jailers treat the office captives — THE SUBSIDIARY, LAME MAN, ONE-EYED MAN, and ONE-ARMED MAN; THE MUTE GIRL, BLIND GIRL, and DEAF GIRL — with an attitude that alternates between indifferent and threatening. Sometimes they let them work. Sometimes they chase them with bloodthirsty dogs.

The Subsidiary is Bartleby the Scrivener meets Cujo as imagined by David Lynch (in Chile). The book contains banal reports, like “MY SKILLS ARE MANUAL,” and “I STAMP THE ORDERS, THE INSTRUCTIONS, THE MANDATES-.” Yet it also transports the reader to frightening places. Many pages have a snapshot-in-the-dark quality to them, and what we see during those flashes is scary. “IT’S THE HOWLING OF A PACK OF HOUNDS BEFORE THE VIOLENCE BEGINS,” Celedón stamps. “THE BLIND GIRL KEEPS STILL WHILE THE DOGS SNIFF AT HER,” and, “SHE’S IN HEAT.”

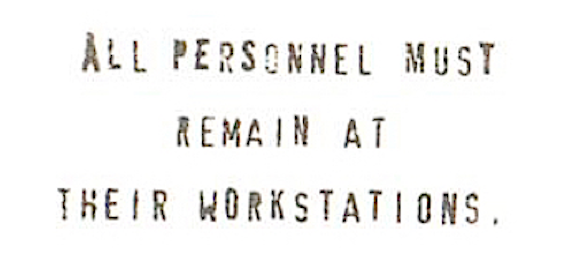

In the spirit of Franz Kafka, Matías Celedón evokes a bureaucratic nightmare that is terrifying in its banality and in its menace. The power remains off for 12 days, and nobody resists the instructions to remain at their stations. Despite its near pointlessness, the narrator maintains an unwavering commitment to his job.

Celedón’s dedication to his farcically technical method stabilizes this harrowing story. He wrote The Subsidiary by taking it on like a clerk — by showing up every day, and selecting and placing individual letters with tweezers. From its technical construction to its tormenting delivery, The Subsidiary enacts the tension between reason and futility in doing work.

You shouldn’t just read The Subsidiary for its eccentric context or its chilling story. You shouldn’t just read this book because of its painstaking commitment to forming words. All of these pieces — each spectacular on their own terms — fix together to create a remarkable reading experience. The Subsidiary releases an extraordinary beast.