If you listen very closely, you can hear it even now: the sound of the human heart beating. Often, in particularly good horror fiction, this sound is the thing that resonates most, the sound of life springing forth from the void of confusion and danger around it. The best horror fiction accounts for the heart’s profound sensitivity — its vulnerability to alarm and suspense — and the best horror writers understand that the heart, as much as the mind, is able to gauge and comprehend the forces, processes, shadows, and shapes of fear.

In many ways, horror fiction is about human beings confronting, with mind and heart, something that is just beyond their understanding. Characters are relentlessly seduced, pursued, threatened, and fascinated by that which eludes their full comprehension. H.P. Lovecraft writes in “Supernatural Horror and Literature” that in horror “a certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces must be present; and there must be …a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature,” validating horror’s power as the genre that uniquely positions and measures man against all that is not-man.

When critics argue that writers of the modern horror genre are leaning more and more toward purely psychological turmoil, and relying less on the jolting scare from monsters or the supernatural, they are only half correct: there was never a practical difference between the terror derived from monsters and the “breathless and unexplainable dread” born from psychological unease. Rather, both types of fear emerge from a change or “suspension” of the “fixed laws of Nature.” If psychological discomfort can feel supernatural, then who is to say, in the genre of possibility, when it is not?

Today, many of most practiced and respected horror authors utilize the shock of monsters and mentally unnerving situations to generate an atmosphere of terror. More and more, modern horror writers play on man’s vulnerabilities in perceiving boundaries, rules, and figures — in assigning terms and description to the problem that confronts him. Fear, then, is the experience of opposing something that is unknowable.

Take, for example, Joe Hill’s new book The Fireman, in which a deadly spore called Dragonscale infects people with black and gold streaks around their body that gradually increase in heat until the person catches fire and burns alive. Hill, who’s certainly proving he can carry the torch of his father (who is Stephen King), breathes new life into the global-contagion mythos by combining the scientific extremism of Michael Crichton with the fable-like surrealism of Ray Bradbury. Hill manages to craft a horror story in which transactions in knowledge — about the spore, about the state of society, about other people — become the most important and most powerful events.

Take, for example, Joe Hill’s new book The Fireman, in which a deadly spore called Dragonscale infects people with black and gold streaks around their body that gradually increase in heat until the person catches fire and burns alive. Hill, who’s certainly proving he can carry the torch of his father (who is Stephen King), breathes new life into the global-contagion mythos by combining the scientific extremism of Michael Crichton with the fable-like surrealism of Ray Bradbury. Hill manages to craft a horror story in which transactions in knowledge — about the spore, about the state of society, about other people — become the most important and most powerful events.

When Harper, a school nurse-turned-quarantine doctor, learns she has contracted the disease in the midst of her early pregnancy, she starts to piece together a book — The Portable Mother — for the child she will never get to raise. Over time, Harper’s book grows to include pictures, hand-drawn portraits, letters, pages of books, and “emergency kisses” so that when “her son [needs] a kiss, he would have plenty to choose from.” As much as the Mother is a gesture and gift of love, it is Harper’s safeguard against the terror of the Dragonscale plague — an assurance that she, at least in some way, will endure the fiery apocalypse. Her ultimate gift to her unborn child is knowledge: of her, of the child’s family, of what life was like before the world burned to ash.

In The Fireman, men like the Marlboro Man and his Cremation Squads, who roam the country seeking the annihilation of people infected with Dragonscale, become monsters through their desire to erase identity, history, and culture. Marlboro Man’s radio broadcasts are terrifying, ugly, sexist rants meant to instill dread in the minds and hearts of Dragonscale survivors. But the survivors understand that knowledge is their greatest asset: “The more we know about him,” one character argues, “the less likely he’ll ever know anything about us.” In a book that expertly weaves together themes of illness, religion, media, love, friendship, and politics, in a book of this size and scale, the terror comes from a single answerless question: “Did [the characters] panic because their bodies were constantly smoking, or did they smoke because their minds were constantly in a state of panic?” The Fireman imagines what happens when the human body cannot recognize itself.

Martin Pousson, in his new book Black Sheep Boy, expertly probes the horror of circumstance, place, family, and sexuality through a disjointed series of stories about a “no-name” narrator growing up in the Cajun region of Louisiana. Pousson establishes psychological drama by nature of the narrator’s birth: he is gay, and he lives in an almost dangerously prejudiced and homophobic place. He is also born in thrall to the dreams his parents have for him (being straight) and the lives they want for themselves: “While Papa conducted an orchestra of memory in the garage, Mama directed a theater of fantasy in the house.” They are all forced to live beyond their understanding — the narrator must somehow cope with his sexuality in his increasingly aggressive world, and his parents must accept their son’s unanticipated and unimaginable sexual orientation.

Martin Pousson, in his new book Black Sheep Boy, expertly probes the horror of circumstance, place, family, and sexuality through a disjointed series of stories about a “no-name” narrator growing up in the Cajun region of Louisiana. Pousson establishes psychological drama by nature of the narrator’s birth: he is gay, and he lives in an almost dangerously prejudiced and homophobic place. He is also born in thrall to the dreams his parents have for him (being straight) and the lives they want for themselves: “While Papa conducted an orchestra of memory in the garage, Mama directed a theater of fantasy in the house.” They are all forced to live beyond their understanding — the narrator must somehow cope with his sexuality in his increasingly aggressive world, and his parents must accept their son’s unanticipated and unimaginable sexual orientation.

Skinwalkers, sexual predators, angels, and superbeings add shock value to the general paranoia. These creatures become mysterious partners, friends, rivals, and of course, monsters while the narrator tries to distance himself from the man his parents want him to be — making his journey into confident adulthood and sexuality one of strangeness and hideousness. At one point in the narrator’s story, when he is living with three crackpot cousins, he realizes, “You could argue about the weight of a fish or the color of its scales. But the name of a thing had a certain authority to it.” And this is true, for the most part, about growing up and accepting things as they are, difficult as they may be. But then the story asks: what happens when a thing or person or event can’t be named? After the narrator’s mother sees her son’s dyed hair and painted face and “the nails on his hand, [black] eyeliner, black nails,” she wonders, “what kind of voodoo [is] that?” Black Sheep Boy frames its fear through tragic misunderstanding, violence, and sexual confusion, and it illuminates the terrible aching divide of understanding between family members.

Robin Wasserman’s Girls on Fire also touches on issues of sexuality and family, but offers a more realist approach to the genre: her characters are teenage girls who are fed up with living in their boring town (plagued by Satanic worship) and are tormented with anxiety over past actions and conversations, family, identity, and sex. Wasserman’s first foray into adult horror fiction — she has built a wonderful career around her YA Seven Deadly Sins series — is a thrilling, nightmarish look into the nature of teenage girl relationships and the lies that can sometimes hold them together. As Nikki, the town’s most popular and conniving starlet, fights with Lacey, a new girl with a harrowing home life, for power and influence over Hannah, dark secrets and masks become the currency of the girls’ malicious war.

Robin Wasserman’s Girls on Fire also touches on issues of sexuality and family, but offers a more realist approach to the genre: her characters are teenage girls who are fed up with living in their boring town (plagued by Satanic worship) and are tormented with anxiety over past actions and conversations, family, identity, and sex. Wasserman’s first foray into adult horror fiction — she has built a wonderful career around her YA Seven Deadly Sins series — is a thrilling, nightmarish look into the nature of teenage girl relationships and the lies that can sometimes hold them together. As Nikki, the town’s most popular and conniving starlet, fights with Lacey, a new girl with a harrowing home life, for power and influence over Hannah, dark secrets and masks become the currency of the girls’ malicious war.

Group power dynamics dominate: guys controlling girls, girls taking advantage of other girls, girls conquering guys, and each of them are victim to a vicious slew of rumors and fabrications. In a town afflicted by Satanism, where boys are believed to conjure evil for pleasure, to be a girl is to “live in fear” over “knowing too well what could happen” to them and their bodies if they get involved with the wrong crowd. Dates and parties are planned precariously around Hannah, for Hannah — Nikki and Lacey repeatedly force her into situations that quickly spin out of her control. They harass her with lies about each other and their past, about pretending to be popular or uncool, until Hannah realizes she is friends with people she does not really know, that to “defeat a monster, you had to embody one.” If she cannot understand the girls around her, then she must learn to play their game. And she does.

This is how Girls on Fire carefully builds its suspense. Nikki and Lacey lie and then lie about their lies, while Hannah’s rather malleable personality and sense of allegiance change with disturbing ease. Although she can barely wrap her head around their teenage War of the Roses, Hannah remains curious. Toward the beginning of the novel, when a popular jock is found dead in the woods, Hannah reveals that she is most disturbed not by his death, not by the violence, but by the fact that someone like him “had secrets — that he had actual, human emotions” similar to hers. She wonders, along with Nikki and Lacey and many girls in the book, again and again what those secrets are, the secrets of a person about to die. Girls on Fire is a study in the macabre and morbid, where characters are faced with the desire to experience someone else’s suffering because it is impossible for them to know what such suffering would be like for themselves; having special knowledge about pain and loss, even if it comes from a “monster,” is preferable to ignorance.

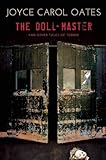

These new novels are just a few examples of many that illustrate the horror genre’s continued use of psychological unease and the supernatural in pursuit of defeating and suspending, what Lovecraft called, the “fixed laws of Nature.” Perhaps more so than the rest, however, Joyce Carol Oates’s The Doll-Master works at the intersection between the natural and supernatural. The book is advertised (all on the cover) as a work of horror, a psychological thriller, and also a dark mystery, which certainly speaks to its multi-dimensional storytelling.

These new novels are just a few examples of many that illustrate the horror genre’s continued use of psychological unease and the supernatural in pursuit of defeating and suspending, what Lovecraft called, the “fixed laws of Nature.” Perhaps more so than the rest, however, Joyce Carol Oates’s The Doll-Master works at the intersection between the natural and supernatural. The book is advertised (all on the cover) as a work of horror, a psychological thriller, and also a dark mystery, which certainly speaks to its multi-dimensional storytelling.

In the book’s title piece, a young boy becomes obsessed with collecting the dolls of his deceased cousin and, under the supervision of a sinister man called only “The Friend,” he begins to deceive his family (and himself) about his unusual habit. Oates cleverly plays on the imagery and meaning of “doll” throughout the book, which manifests most clearly in “The Doll-Master,” as the young boy is swept up by The Friend and controlled like a stringed puppet — only, in the boy’s view, he is simply following orders and fulfilling a job. He is willing himself away to a role (the Doll Master) that he never quite understands: “For it has been revealed to me as a fact, that where the dull-essential nature of our lives is eliminated, such as age, identity…the thrilling-essential is revealed.” Oates’s horror involves the giving away of knowledge to circumstances and individuals beyond the “dull-essential nature” of existence.

While these books are evidence of the genre’s concern with human knowledge and comprehension, they also show that supernatural beings and psychological discomfort are both still effective means of evoking fear. They shock, they unnerve, and they ask of readers what Edgar Allan Poe once asked: “The boundaries which divide Life from Death are at best shadowy and vague. Who shall say where the one ends, and where the other begins?”

Image Credit: Pixabay.