1.

For writers, literary inheritance is inexorable. Many suppress, some overcome, and a great deal are burdened by what Harold Bloom called the “anxiety of influence.” The writers who transcend their inheritance might allude to their precursors, tip their cap, and maybe even insert a line or two from the master into their work as a sign of respect.

But contemporary Spanish authors have taken a different approach. Refusing to settle for polite allusion, they instead dig up the masters and plop them into their narratives. Take Carlos Rojas’s The Ingenious Gentleman and Poet Federico García Lorca Ascends to Hell, where the Garcia Lorca sits in hell watching his life acted out on stage. In The Savage Detectives, Roberto Bolaño’s itinerant characters embark on a quest for their literary gods. Enrique Vila-Matas’s novels pathologize literary influence; characters succumb to literary diseases (Montano’s Malady) and enter Hemingway lookalike contests.

But contemporary Spanish authors have taken a different approach. Refusing to settle for polite allusion, they instead dig up the masters and plop them into their narratives. Take Carlos Rojas’s The Ingenious Gentleman and Poet Federico García Lorca Ascends to Hell, where the Garcia Lorca sits in hell watching his life acted out on stage. In The Savage Detectives, Roberto Bolaño’s itinerant characters embark on a quest for their literary gods. Enrique Vila-Matas’s novels pathologize literary influence; characters succumb to literary diseases (Montano’s Malady) and enter Hemingway lookalike contests.

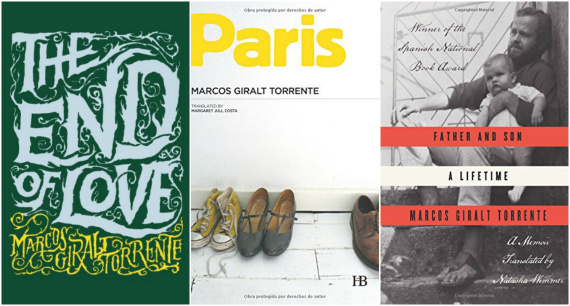

So it’s no surprise that Spain would produce Marcos Giralt Torrente, a writer fixated on influence and inheritance. Giralt Torrente is already well-respected in Spain, where he has won the Herralde Novel Prize and the Spanish National Book Award, but his name will be fairly new for most English readers. In the past year alone three of his books—the story collection, The End of Love, a novel, Paris, and his memoir, Father and Son: A Lifetime—have been published as English translations. Giralt Torrente is the son of painter Juan Giralt and the maternal grandson of esteemed Spanish novelist, Gonzalo Torrente Ballester. He would seem, therefore, the perfect candidate to carry the torch of his contemporaries. And yet, Giralt Torrente is less concerned with literary influence than he is with familial influence, the inheritance that haunts the person regardless of whether the author emerges.

2.

Of the three books recently published, Giralt Torrente’s first novel, Paris, serves as the best introduction. Here he begins to develop the themes of memory, fidelity, deceit, and family that recur throughout his work. It is a dense, deeply reflective novel, narrated by a middle-aged man trying to understand his parents’ inexplicable marriage. The narrator is mesmerized and obsessed with his mother, a controlling, strong-willed woman whose selective disclosures have shaped what the narrator remembers from his childhood: “I have no way of finding out if she is also the reason I don’t know certain other things, things she deliberately kept from me. When our knowledge of a subject depends on the words of others, we can never be sure if they’ve told us everything or only a part.”

Of the three books recently published, Giralt Torrente’s first novel, Paris, serves as the best introduction. Here he begins to develop the themes of memory, fidelity, deceit, and family that recur throughout his work. It is a dense, deeply reflective novel, narrated by a middle-aged man trying to understand his parents’ inexplicable marriage. The narrator is mesmerized and obsessed with his mother, a controlling, strong-willed woman whose selective disclosures have shaped what the narrator remembers from his childhood: “I have no way of finding out if she is also the reason I don’t know certain other things, things she deliberately kept from me. When our knowledge of a subject depends on the words of others, we can never be sure if they’ve told us everything or only a part.”

His memories, so thoroughly contaminated by her, cannot be trusted. Yet memory remains “a great temptation.” Tempting and addictive. A burden for those who seek comfort, for to remember is to struggle, to disentangle received narratives, reorder them, in a fruitless attempt to uncover the truth.

Not big T truth—though that’s all over Paris—but the basic truth, what happened and why. And what’s marvelous about Paris is that, despite its relative lack of action, the novel holds our attention, as we, too, read to uncover what happened. This is partly due to Giralt Torrente’s careful plotting, and partly due to a swaddling, syntactical empathy.

We want the narrator to get what he wants. Giralt Torrente doesn’t achieve this by making his character likeable, or vulnerable. Empathy, here, is achieved through the syntax. Giralt Torrente is a masterful sentence writer. He learned to write on a diet of Henry James, Faulkner, Proust, and Thomas Bernhard. Though his sentences, packed with dependent clauses and parenthetical flights, rarely reach the multi-page length of a Faulkner or Bernhard sentence, they beautifully and patiently trace the nuanced digressions of his characters’ minds. Here is a passage from Paris:

When we think about the past, it’s hard to resist both dividing it up into blocks in accordance with the pattern of events that have made the most impression on us and attributing powers to it that it does not have, allowing ourselves to believe that the arrival of a particular date had the ability to work some radical transformation on us. Until the death of my father, we say, I was like this or like that, when we should really say that on such and such a date, something that had already existed inside us began to make itself manifest or visible.

To borrow from William Gass, these sentences “contrive (through order, meaning, sound, and rhythm) a moving unity of fact and feeling.” As we read we think with the narrator thinking through the idea. The statement is felt rather than proven. And the use of the first person plural conflates narrator and readers. But there is a difference between Giralt Torrente’s use of the first person plural, and Javier Marias’s, who uses this technique quite often. In Marias “we” is broad and inclusive, sweeping through Madrid and Oxford, while in Giralt Torrente the “we” is restrictive, limited to his characters and his readers. We feel caught in the narrator’s mind, hearing it obsessively reassess, which is perhaps most reminiscent of Bernhard, where each sentence seals off the world like Montresor stacking the bricks in our tomb.

This insularity is heightened by Giralt Torrente’s reliance on first person in all three recent books. He describes his narrators as “witnesses, in general cultivated and very reflective, for whom doubting their perceptions, questioning them and clarifying them, is their way of being in the world.” Father and Son: A Lifetime indicates that is also how Giralt Torrente exists in the world. The memoir, written shortly after Giralt Torrente’s father died from cancer, meticulously explores their strained relationship in an attempt to “understand what [they] lost; where [they] got stuck.” Comprised of many short fragments, the memoir weaves together a loose chronology of their lives—the galleries they visited, the absences, the arguments, the conversations and women they shared—with lyrical, paratactic reflections: “We got stuck because his consummate solipsism made him accept the unspoken and I demanded action. . . . we both thought we deserved more than we had. . . . we got stuck because I made him the creditor of a debt that I tried to call in when it had already expired.”

Inheritance, for Giralt Torrente, is not strictly filial, but existential. The relationship between father and son in Father and Son, lets him explore personhood more broadly. The search for where they got stuck is inseparable from the search for identity. Was stubbornness to blame? Competiveness? And if they share those traits shouldn’t the son be let off the hook? How relieving it is to trace our most toxic traits to our parents. Inheritance is expiation—but it’s also original sin. Giralt Torrente’s work suggests character is inherent and untraceable. Discovering the seed of ourselves is as easy as pinching hydrogen atoms out of a river.

Perhaps this is why we often concede to our selfhood. As Giralt Torrente writes in Paris, our character “depends not on the appearance or disappearance of new characteristics but rather on the way in which certain already-existing characteristics win out over others.” To refuse to accept yourself is to grasp with irritable, buttery fingers. So we pivot to the question of when. Not when we became who we are—the narrator in Paris rightly debunks that search—but the discernible when: the choice that made everything different, the instant we acted a certain way and thus cemented the future. These are the moments that plague conspiracy theorists, jilted lovers, and armchair quarterbacks.

In The End of Love, Giralt Torrente’s story collection, many characters obsess over such moments. The speaker in “We Were Surrounded by Palm Trees,” reflecting on the final days of his relationship, says, “one of memory’s most powerful tendencies is to identify those moments when it would still have been possible to change the course of events.” He has been seduced by this moment. Memory loves to convince us we’re free, in control. It fills our heads with revisions, the house we might’ve owned, lovers we could’ve loved, jobs that would’ve fully inspired us, if only we’d kept playing piano or told Chris how he felt. But choice, for Giralt Torrente, is an illusion. Had the narrator in acted differently, he may have lengthened his relationship, but he would not have saved it.

This sentiment is powerfully expressed in the collection’s second story, “Captives.” It follows the narrator’s attractive older cousin, Alicia, and her husband, Guillermo. They were a young and beautiful couple, wealthy and itinerant, traveling to distract themselves from their loveless marriage. Alicia sends the narrator postcards and letters, but eventually their marital woes become exasperating. “I lost patience with [Alicia’s] lack of decisiveness. I thought that, as she seemed destined to leave Guillermo, any delay was stupid. Clearly, I underestimated her.” The relationship persists. And with Guillermo dying, the narrator visits the couple. They live on the same estate, in two separate houses, neither able to leave the other. On his death bed, Guillermo explains:

We believe we have an impregnable interior, a place where we are defended, where we can steel ourselves, but then it turns out that even we can’t get in. Even the most elemental things, our dreams, elude our will. How different everything would have been if my desire had obeyed me. Deep down, we have been equals, even in that. In her own way, Alicia and I have been captives of the same incapacity. [italics Giralt Torrente’s]

The will, here, exists, but it is in no way free. It is free the way dogs at the kennel are free to bark as loud as they like. To fully understand one’s desires is to see the discord between what is desired and what is obtained. In Father and Son, this is expressed in extended passages of longing—“I liked it when he considered me an equal . . . I liked to match his dilettantish hedonism . . . I liked to invade his territory . . . I wanted to learn, to be like him, and I imitated him”—which are repeatedly undercut: “But I hardly ever succeeded. I lacked so much of the knowledge I know he possessed. We squandered so many opportunities.” This is not simply weltschmerz. It is a further expression of Giralt Torrente’s somewhat Aristotelian conception of personhood: people do not change, they merely reach their inherent potential.

Giralt Torrente is, in other words, a fatalist resistant to fatalism. He isn’t trying to teach his characters lessons. He doesn’t think they are wrong for trying to pinpoint the moments when life changes, when personalities shift, but the ordeal is never successful. Giralt Torrente empathizes with the futile attempt to fully understand who we are. In Father and Son, death reminds him that “everything comes to an end, that there’s no redemption, that what wasn’t done can no longer be done.” Such a bleak realization, learned in life but expressed in the memoir, suggests that Giralt Torrente, knowing there is no redemption, still writes the memoir that strives to redeem its subjects.

There is nothing sensational, no gimmicks or zany protagonists, in Giralt Torrente’s fiction. The influence of Henry James is apparent. Giralt Torrente writing feels classically devoted to storytelling. His books are haunting, complex, and engrossing, peopled with well-developed, flawed characters that are obsessive and voluble, yet Giralt Torrente, for all the freedom he gives them to speak, never cedes control of his stories. One pleasure of reading his work is unlocking their structures, seeing time subtly manipulated, seeing what the characters do not, and may never, understand. His books are charged and evocative, loaded with precise, intelligent sentences that create worlds that are easy to enter and impossible to escape.