1.

This year, to celebrate the centennial of the great Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal, the University of Chicago Press published an early short-story collection previously unavailable in English. Rambling On: An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of Gab was written and published in the 1960s, a mid-career work bringing together some of his best short fiction, like “The Feast” and “A Moonlit Night.”

In the final story, “An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of Gab,” written by Hrabal as part postscript, part manifesto, he writes,

In the final story, “An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of Gab,” written by Hrabal as part postscript, part manifesto, he writes,

I’m a corresponding member of the Academy of Rambling-on, a student at the Department of Euphoria, my god is Dionysos, a drunken, sensuous young man, jocundity given human form, my church father is the ironic Socrates, who patiently engages with anybody so as to lead them by the tongue and through language to the very threshold of nescience, my first-born son is Jaroslav Hašek, the inventor of the cock-and-bull story and a fertile genius and scribe who added human flesh to the firmament of prose and left writing to others, with unblinking lashes I gaze into the blue pupils of this Holy Trinity without attaining the acme of vacuity, intoxication without alcohol, education without knowledge, inter urinas et faeces nascimur.(We are born between urine and feces.)

Bohumil Hrabal was born near the beginning of World War I in Brno, in the Austro-Hungarian empire. He was raised by a gallery of colorful relatives, including an uncle who served as an early model for the gregarious and unscrupulous type that populated his later novels. His legal studies at Charles University in Prague were interrupted by the Second World War. After the Communists took over, he worked as a stage hand and industrial worker. He published one book of poetry in the late 1940s, but didn’t publish fiction until he was 42.

When he did begin writing stories and novels, his methods for composing fiction were radical. According to David Short, one of his translators, the Czech writer was a prolific cut-and-paste stylist. The expansive tone and patient rhythms of Hrabal’s writing belies just how drastic his revisions were. According to Short, Hrabal uses “words unknown to anyone;” his cryptologisms still confound lexicographers.

Married in 1956, Hrabal traveled between a co-op flat in a northern district of Prague and a chalet in the Kersko in central Czechoslovakia. He routinely fled the cramped Soviet-style apartment for the more idyllic countryside. A film adaptation of his novel Closely Watched Trains came out in 1967, and it won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film, a high point of the Czech New Wave. According to the film historian Philip Kerr, Hrabal preferred the movie over his novel. Less than two years after the high point of his success, the Soviets invaded, removed the reformer Alexander Dubček, and initiated “normalization.”

Married in 1956, Hrabal traveled between a co-op flat in a northern district of Prague and a chalet in the Kersko in central Czechoslovakia. He routinely fled the cramped Soviet-style apartment for the more idyllic countryside. A film adaptation of his novel Closely Watched Trains came out in 1967, and it won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film, a high point of the Czech New Wave. According to the film historian Philip Kerr, Hrabal preferred the movie over his novel. Less than two years after the high point of his success, the Soviets invaded, removed the reformer Alexander Dubček, and initiated “normalization.”

In post-normalization Czechoslovakia, his manuscripts were heavily censored by the publisher Československý Spisovatel. Nevertheless, Hrabal was being praised internationally as a prose master. He influenced Philip Roth and Louise Erdich. Roth, as the editor of the series Writers from the Other Europe, called Hrabal, in 1990, “one of the greatest living European prose writers” and it’s difficult to imagine the barbed mania of Sabbath’s Theater or the absurd feast scene in American Pastoral without Hrabal’s earlier Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age or I Served the King of England.

In post-normalization Czechoslovakia, his manuscripts were heavily censored by the publisher Československý Spisovatel. Nevertheless, Hrabal was being praised internationally as a prose master. He influenced Philip Roth and Louise Erdich. Roth, as the editor of the series Writers from the Other Europe, called Hrabal, in 1990, “one of the greatest living European prose writers” and it’s difficult to imagine the barbed mania of Sabbath’s Theater or the absurd feast scene in American Pastoral without Hrabal’s earlier Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age or I Served the King of England.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Hrabal was noticeably silent and did not sign Charter 77. In the cant of Soviet occupation, he “released self-critical statements that made it possible for him to publish.” He died in 1997, after falling out of a fifth-floor hospital window while feeding a cat.

2.

“Ambiguous” and “ambivalent” are overworked terms in the critic’s vocabulary, and vague. The words are accurate for Hrabal, though: a writer engaged with how meaning can shift in the telling and understanding of a story. He dramatizes story-telling (anecdotes, confession, harangue) and he also dramatizes interpretation. Hrabal is preoccupied with how a story can seem to change with an alteration of mood or perspective. How, to pick up a concept from Ludwig Wittgenstein, understanding is deeply aspectual.

In his posthumously published Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein explained this concept of “seeing-as.” First, you see a man’s face. Then, you might see a resemblance between the face and another face, a familial resemblance. You haven’t seen the face differently, but an “aspect” of the face has “dawned on you.” You now see the face as resembling another face.

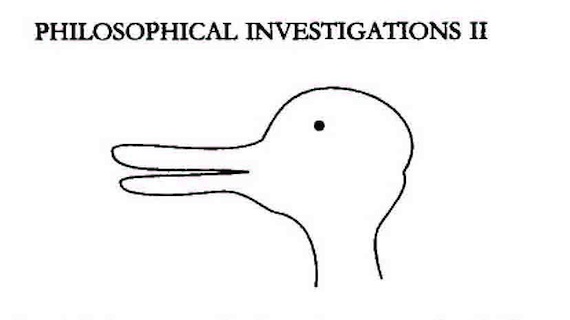

Or take the picture of the “duck-rabbit:” Looking at the picture, you might see the “duck,” then see the “rabbit.” There’s a cognitive shift between seeing the one and seeing the other. Nothing has changed about the picture. Wittgenstein writes, “I distinguish between the ‘continuous seeing’ of an aspect and the ‘dawning’ of an aspect.”

Wittgenstein writes: “If you ask me what I saw, perhaps I shall be able to make a sketch which shows you; but I shall mostly have no recollection of the way my glance shifted in looking at it.”

Produced in the Academy of Rambling-on, at the Department of Euphoria, Hrabal’s fiction teases out these effects. His protagonists begin as typically superficial readers, who linger on those damaged surfaces or mordant anecdotes for a little longer than they’re comfortable with. They glimpse briefly past the equivocations and the evasions. Finally, their tone becomes urgent and fraught, and their perspective begins to disintegrate.

Translated by Short, the story “Friends” takes up what seems like a hopelessly trite premise, two handicapped friends who teach a friend a deeper life lesson:

And the two friends each had their own truth, their moral fibre was so awesome that all who knew Lothar and Pavel, however slightly, if ever they were a bit despondent, if ever they began to wonder if life was worth living under such-and-such conditions, they’d all…, me too, when, at moments of such blasphemous thoughts, I think of Pavel and Lothar, I feel ashamed of myself compared to the moral compass that backs Pavel and Lothar’s view of the world.

Drawing inspiration from the handicapped? A cliché, sure. Editors who draw a red line through each “batted eyelash” or “on the horizon,” though, would be well-advised to read Hrabal closely, because he understands how cliché eloquently obscures fatigue, despair, and tragedy — writers who work under juntas and dictatorships are especially familiar with the sinister authority of cliches.

Hrabal turns the cliché inside out toward the end of the story. The narrator accompanies them on a trip in which they are bizarrely hassled by a police officer who is interested in how well Lothar speaks Czech. He takes them home and then waits outside the house, watching the two men struggle up the stairs.

I saw Lothar disappear from his wheelchair and then I saw him, like when soldiers crawl through hostile territory, haul himself up with his powerful arms one step at a time, dragging his powerless legs behind him…and then Pavel the same, by his elbows… and I saw how they both had to pause half-way, how though the trip to the pub hadn’t got the better of them, those twelve stairs had, and they had to summon all their strength, turn and turn about, to haul themselves up to the top.

The protagonist Ditie, of Hrabal’s masterpiece I Served the King of England, hides behind cliché, too. Ditie repeats the phrase, “how the unbelievable came true,” in the novel, by my count 12 times.

But the narrator’s trite expressions seem to gloss over his own moral dubiousness. One of the finest novels of the 20th century, I Served the King of England was written in 1971, only a few years after the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia and the removal of President Dubcek from office. Shortly thereafter, Hrabal began working on the novel, a searing indictment of Czech complicity during World War II, with a protagonist that affects powerlessness and servility.

After being inspected by Nazi doctors for his suitability to marry and procreate with a German woman, Ditie marries Lise. She brings him a suitcase full of stamps. “At first I didn’t realize how valuable the contents were,” the narrator explains, “because it was full of postage stamps, and I wondered how Lise had come by them.” She explains to him that “after the war they would be worth a fortune, enough to buy us any hotel we wanted.”

As the Nazis are losing battles, Ditie is mistaken for a resistance fighter — according to his explanations, he is often mistaken for being much worse (a thief, a murderer) and much better than he actually is (an anti-Nazi fighter and activist several times). The interrogation becomes a happy accident, since his being targeted by the Nazis will gain him purchase as a subversive in post-war Prague. After being released, Ditie helps an elderly prisoner on a long journey to his home.

“I was doing this not out of any kindness,” Ditie explains, while hesitating to return home, “but to give myself as many alibis as possible once the war was over, and it would be over before we knew it.”

Though Ditie goes to great lengths to exculpate himself from the horrors of Nazism, his own alibi-forging strains credibility: how could he have married a woman like Lise and not recognized her involvement? Wouldn’t the gaps and evasions in his story indicate a more significant crime? Is his confession more significant because of the large-scale omissions that seem implied?

3.

Hrabal, following Joyce, offers up several instances of how mirrors and reflections can misapprehend our true selves, or how we can misapprehend ourselves in reflection. In Joyce’s “Araby,” the narrator’s reflection gives rise to misconceived feelings of piety and self-loathing.

Hrabal picked up the theme in I Served the King of England. The main character becomes a waiter in a prominent hotel and becomes entranced by how pomp can elide one’s own vulnerable identity:

I saw myself in the mirror carrying the bright Pilsner beer, I seemed different somehow, I saw that I’d have to stop thinking of myself as small and ugly. The tuxedo looked good on me here, and when I stood beside the headwaiter, who had curly gray hair that looked as though a hairdresser had done it, I could also see in the mirror that all I really wanted was to work right here at this station with this headwaiter, who radiated serenity, who knew everything there was to know…

Being a waiter requires Ditie to cultivate a kind of passive omniscience. The headwaiter, not Ditie, served the King of England. When a character asks how he knows that a couple is Bavarian, or how a customer likes his veal, the headwaiter simply says, “I served the King of England.”

High Culture is another way Hrabal’s protagonists conceal their motives. Like By Night in Chile’s priest-critic, Ditie’s confession is gilded with references to literature, culture, sophistication, but in stark denial of any moral purpose. The narrator of Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age tells his employer, “Like Goethe, I have a weak heart and was more inclined to poetry, which slowed them down for a while.” Ditie is entranced by the rituals and culture of European decadence and hides behind them.

After a lavish feast during which the exiled Ethiopian leader Haile Selassie honors him with a sash, the protagonist is accused of stealing a spoon. Devastated, he takes a taxi to a remote spot in the countryside. He laughs and tells the taxi driver he plans to hang himself. He says it impulsively, but saying the words propels him inextricably towards suicide.

Seriously? The cab driver said, laughing. With what? He was right, I had nothing to do it with, so I said, My handkerchief. The driver got out of his cab, opened the trunk, rummaged around with a flashlight, then handed me a piece of rope. Still laughing, he made an eye in one end and ran the other end through it to make a noose and showed me the proper way to hang myself.

Ditie stumbles into the stand of darkened woods.

I made up my mind to hang myself. As I knelt there, I felt something touch my head, so I reached up and touched the toes of a pair of boots, and then I groped higher and felt two ankles, then socks covering a pair of cold legs. When I stood up, my nose was right up against the stomach of a hanged man.

That reversal might seem familiar. Philip Roth re-imagined the scene in Sabbath’s Theater, a novel deeply influenced by Hrabal. In that scene, the puppeteer Mickey Sabbath has gone to his mistress’s grave to pay homage by writhing in the dirt and simulating sex. As he’s approaching the grave, he sees another figure near the grave:

When Sabbath saw Lewis bending over the grave to place the bouquet on the plot, he thought, But she’s mine! She belongs to me!

What Lewis did next was such an abomination that Sabbath reached crazily about in the dark for a rock or a stick with which to rush forward and beat the son of a bitch over the head. Lewis unzipped his fly…

Roth follows Hrabal in a mode of amplified realism — never magical but wryly attuned to absurdity — and featuring narrators and protagonists whose appetites match their verbosity. Hrabal’s palpable influence, acknowledged by writers such as Roth and Erdich, is a reminder of how vital his work has been to American contemporary fiction.

4.

Months before the Velvet Revolution, at a time when the Czech Communist party was showing its frailty but its decline did not seem inevitable, Hrabal reported on Czech politics in early 1989, with excerpts appearing in the New York Review of Books. He wrote in direct, austere sentences, as if acknowledging that irony was giving way to deeper melancholy impulses:

I walked down deserted Parizska Avenue. A police car quietly pulled up at the curb, a man got out and began quietly placing parking tickets on the windshields of illegally parked cars, then quietly the headlights turned toward Maison Oppelt, from the fifth floor of which Franz Kafka once wanted to jump, and then I stood all alone in the square. The place was deserted. I sat down on a bench and began to reflect…In front of me loomed the monument to Master Jan Hus.

In his afterword to Rambling On, Václav Kadlec points out how Hrabal had begun to focus on longer fiction by the late 1960s, eventually leading to the triumph of I Served the King of England and Too Loud a Solitude. But Hrabal was a great short-story writer, whose works were strained with pathos, absurdity, and beauty. The stories in Rambling On also show a unique range, partly because in 1960s Czechoslovakia, he was able to experiment with theme and language more freely and partly because he is still deciding on a tone, a style, and a subject.

Read the stories. Read the novels. Just read Hrabal.