Tom Nissley’s column “A Reader’s Book of Days” is adapted from his book of the same name.

July is the month of revolutions, so much so that in France’s upheaval even the month itself was swept away. The French Revolution that began with the liberation of the Bastille on July 14 tried to reinvent many traditions from the ground up—the metric system lasted longer than most—and the calendar was among them: under the new regime 1792 was declared Year I, with 12 newly defined months of three ten-day weeks each. (Since that only adds up to 360, the five or six days left over became national holidays, les jours complémentaires, at the end of the year.) The poet Fabre d’Églantine was given the task of choosing names for the new months, among them the two that overlapped the traditional span of July: Messidor, from “harvest,” and Thermidor, from “heat” (British wags were said to have suggested  “Wheaty” and “Heaty” as local equivalents). Each day of the year received an individual name too, inspired by plants, animals, and tools: In Year II, for example, luckless Fabre d’Églantine was executed for corruption by his own revolution on Laitue (Lettuce), the 16th day of Germinal. He handed out his poems on his way to the guillotine.

“Wheaty” and “Heaty” as local equivalents). Each day of the year received an individual name too, inspired by plants, animals, and tools: In Year II, for example, luckless Fabre d’Églantine was executed for corruption by his own revolution on Laitue (Lettuce), the 16th day of Germinal. He handed out his poems on his way to the guillotine.

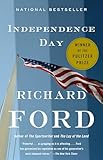

By comparison, America’s revolution hardly altered its calendar, except for the new Fourth of July celebration (which didn’t become an official federal  holiday until 1870). For fiction that evokes the American Independence Day, you can turn to Ross Lockridge Jr.’s nearly forgotten epic, Raintree County, which uses the single day of July 4, 1892, to look back on a century of American history, while George Pelecanos’s King Suckerman crackles to a final showdown at the Bicentennial celebration in Washington D.C., and Frank Bascombe, in Richard Ford’s Independence Day (a Pulitzer winner like Raintree County), attempts a father-son reconciliation with a July Fourth weekend visit to those shrines to American male bonding, the baseball and basketball Halls of Fame.

holiday until 1870). For fiction that evokes the American Independence Day, you can turn to Ross Lockridge Jr.’s nearly forgotten epic, Raintree County, which uses the single day of July 4, 1892, to look back on a century of American history, while George Pelecanos’s King Suckerman crackles to a final showdown at the Bicentennial celebration in Washington D.C., and Frank Bascombe, in Richard Ford’s Independence Day (a Pulitzer winner like Raintree County), attempts a father-son reconciliation with a July Fourth weekend visit to those shrines to American male bonding, the baseball and basketball Halls of Fame.

Here is a list of suggested reading for the heat and upheaval of July:

The Federalist Papers by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay (1788)

The Federalist Papers by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay (1788)

Anybody can have a revolution: the real achievement of the American experiment was building a system of government that could last, as argued for in these crucial essays on democracy and the balance of powers.

Autobiography by John Stuart Mill (1873)

In July 1806, the scholar James Mill challenged a fellow new father to “a fair race with you in the education of a son.” It’s hard to imagine Mill didn’t win: his son, John Stuart Mill, was reading Greek at three and was a formidable classicist by 12. His memoir of his precocious childhood remains a legend of Victorian education.

The Worst Journey in the World by Apsley Cherry-Garrard (1922)

The Worst Journey in the World by Apsley Cherry-Garrard (1922)

No Antarctic tourist would choose the height of the southern winter for a visit, but that’s when emperor penguins nest, so Cherry-Garrard and two companions set out on a foolhardy scientific expedition across the Ross Ice Shelf in the darkness of the Antarctic July, a “Winter Journey” that became the centerpiece of Cherry-Garrard’s classic account of the otherwise doomed Scott Expedition.

“Why I Live at the P.O.” by Eudora Welty (1941)

Why? Because they all ganged up on her: Mama slapped her face and Papa-Daddy called her a hussy and even Uncle Rondo threw a package of firecrackers into her bedroom at 6:30 in the morning, all because Stella-Rondo came home on the Fourth of July and turned them all against her, that’s why.

The Manchurian Candidate by Richard Condon (1959)

The Manchurian Candidate by Richard Condon (1959)

Before there was John Frankenheimer’s film in 1962, there was Condon’s original Cold War fantasia—the direct source of most of the movie’s deliciously bizarre dialogue and convoluted paranoia—which begins with an Army patrol that goes missing in Korea in July before being saved by their sergeant, Raymond Shaw, the finest, bravest, most admirable person they’ve ever known.

The Great Brain Reforms by John D. Fitzgerald (1973)

The Great Brain Reforms by John D. Fitzgerald (1973)

The fifth of Fitzgerald’s eight Great Brain books is perhaps the finest and most dramatic in the superb series for kids set in turn-of-the-century Utah, with a story of a rigged Fourth of July tug-of-war between the Mormons and the Gentiles and a rare comeuppance for Tom, the charming, swindling Great Brain himself.

The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara (1974)

“It rained all that night. The next day was Saturday, the Fourth of July.” There’s no danger of spoiling the ending of Shaara’s Pulitzer-winning novel of Gettysburg by giving away its final words, but knowing the battle’s outcome makes the drama no less appealing.

Saturday Night by Susan Orlean (1990)

Saturday Night by Susan Orlean (1990)

Orlean’s first book, a traveling celebration of the ways Americans spend their traditional night of leisure—dancing, cruising, dining out, staying in—follows no particular season, but it’s an ideal match for July, the Saturday night of months, when you are just far enough into summer to enjoy it without a care for the inevitable approach of fall.

Paris Stories by Mavis Gallant (2002)

What better way to celebrate Canada Day and Bastille Day (and Independence Day, too, for that matter) than with the stories of Montreal’s great expatriate writer, who left empty-handed for Paris with a plan to make herself a writer of fiction before she was 30 and found an American audience for her stories in The New Yorker for six decades afterwards.

Remainder by Tom McCarthy (2005)

Remainder by Tom McCarthy (2005)

It’s July 11 and everything is in place: the glum pianist playing Rachmaninoff, the liver lady frying liver in a pan, the motorcycle enthusiast clanging in the courtyard, and the staff ready behind the scenes for the first re-enactment in McCarthy’s relentlessly provocative (and diabolically approachable) experiment in fiction, in which a suddenly wealthy man’s attempt to recreate his own fleeting past exposes the limits and seductions of memory and the tyranny of unlimited power.

The Damned Utd by David Peace (2006)

Brian Clough’s unlikely decision in 1974 to manage Leeds United, the club that had once been his bitterest rival, began a spectacularly disastrous 44-day summer reign that Peace transformed, with his propulsive and obsessive style, into what many have called the greatest novel on English football.

Call Me by Your Name by André Aciman (2007)

Call Me by Your Name by André Aciman (2007)

“This summer’s houseguest. Another bore.” Hardly. For teenage Elio, the intrusion of a young American academic into his family’s Italian summer sets off a summer’s passion whose intensity upends his life and still sears his memory in Aciman’s elegant story of remembered, inelegant desire.

Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn (2012)

Five years are all it’s taken for the marriage of Amy and Nick, a once-high-flying media couple, to curdle, and Amy’s disappearance on their wedding anniversary, July 5, sets off this twisted autopsy of a marriage gone violently wrong.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.