A few weeks ago, I listened to Maya Angelou’s 1987 appearance on Desert Island Discs. The host was Michael Parkinson, a great interviewer who struggled rather sadly to connect with this particular castaway. The low point of the conversation is almost certainly this:

“You described yourself as six foot, black and female. I want to ask you a question. It might sound silly, but it’s a serious question. Have you ever wished you were six foot, white and male?”

Of course, most of us will experience an involuntary constriction of the chest when a privileged white man says to a member of any other demographic “but wouldn’t you like to me more like me?” Unsurprisingly, Angelou laughed, said no, and gave a charming, obfuscatory answer that precluded further discussion of the subject.

But while Parkinson should have known better, it is daunting to write about Maya Angelou from a cultural remove. Since her death on Wednesday, I have struggled to communicate anything beyond the fact that I loved her and am terribly sorry that she’s gone. Even that feels like appropriation. And yet, I’ve listened to Angelou read Letters to My Daughter — the best way to enjoy her work — and I take her at her word when she says the following:

But while Parkinson should have known better, it is daunting to write about Maya Angelou from a cultural remove. Since her death on Wednesday, I have struggled to communicate anything beyond the fact that I loved her and am terribly sorry that she’s gone. Even that feels like appropriation. And yet, I’ve listened to Angelou read Letters to My Daughter — the best way to enjoy her work — and I take her at her word when she says the following:

“I gave birth to one child, a son, but I have thousands of daughters. You are Black and White, Jewish and Muslim, Asian, Spanish speaking, Native Americans and Aleut. You are fat and thin and pretty and plain, gay and straight, educated and unlettered, and I am speaking to you all.”

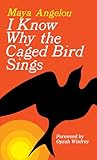

This week’s torrent of grief hasn’t been for a public figure, it’s been much more personal than that. We are grieving a friend, a sister, a mother. Since the publication of I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings in 1969, Angelou has used her own life as a channel for universally valuable truths about racism, poverty, gender, violence, relationships, rape, family, motherhood, loss, equality, hope.

This week’s torrent of grief hasn’t been for a public figure, it’s been much more personal than that. We are grieving a friend, a sister, a mother. Since the publication of I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings in 1969, Angelou has used her own life as a channel for universally valuable truths about racism, poverty, gender, violence, relationships, rape, family, motherhood, loss, equality, hope.

When I first read Angelou’s description of being raped, it was about 10:30 on a Sunday night and I was travelling home on the Tube. I knew it was going to happen and I tried to brace myself, but who could prepare for the frank, vivid brutality of the attack that left the seven year old feeling “like an old biscuit, dirty and inedible.” As soon as I began reading the chapter, I wished I hadn’t, wished I had more time to prepare, to read and feel that pain alone. My house in North London was about a 10 minute walk from the Tube station and I called my partner and spoke to her the whole way — too frightened to face the darkness of the street or the world on my own.

Yet that is how pain works in Maya Angelou’s writing — indiscriminately elbowing its way into perfectly ordinary, contented experience. On the day she was raped (which is how she always described it, although obituaries have largely referred to “sexual abuse”), the young Angelou was about to go out to the library, where she spent most Saturday afternoons.

The pain of segregation became clear when she and her brother attended the movies and were forced to sit on a dangerous, dirty balcony. And that memory resurfaced many years later when she stood to speak at a high-profile ceremony attended by the “most glamorous actors and actresses of the day,” leaving her incapable of delivering her prepared remarks and prompting a rumour that she had blanked out due to drugs.

And days after she returned to the U.S. from Ghana to work with Malcolm X, buoyed with hope for black Americans, he was shot and killed.

Although Angelou is celebrated for her resilience, and rightly so, her repeated traumas were devastating in their impact. They were, in her words, “times when my life has been ripped apart, when my feet forget their purpose and my tongue is no longer familiar with the inside of my mouth.” Still, she shared many of those traumas and, as countless publications have noted this week, her memoirs will almost certainly be her greatest legacy. By consciously writing non-fiction, Angelou stripped us of any possible shield or shred of wool. We can’t escape the pain in her work. When reading fiction, even fiction we know to be largely autobiographical, we have an emergency exit from pain, retreating into the childhood assurance that “it’s only make believe.”

That said, some critics have questioned whether Maya Angelou’s memoirs are strictly truthful. They feature the tropes of literary fiction, there are discrepancies between the different texts, the dialogue is too extensive and too stylish to be entirely accurate, and major “characters” come out smelling suspiciously like roses. Angelou’s mother and frequent muse, Vivan Baxter, is portrayed as a beautiful, strong, caring person, despite the fact that she dispatched her children, three and five, to live with their grandmother and all but disappeared from their lives for many years. Bearing all that in mind, can we still categorize Angelou’s works as autobiographies? Should they still be treated as honest insights into the life and experience of black American women?

The obvious response is that when it comes to memoir — or indeed any form of biography — there are no clear lines between fact and fiction. This is the kind of ambivalent answer I frequently gave as a hungover university student who hadn’t read the book being discussed, but in this case, I actually believe it’s correct. Writing and editing the story of a life inevitably involves emphasis, embellishment, narrative-creation, exclusion of important detail. The auto-biographer, purely by virtue of her extreme investment in the subject, can never be a reliable narrator. The most we can expect is that she will honestly communicate her truth. Surely that kind of honest communication comprised Angelou’s life work?

Like many writers from oppressed communities, Angelou was consciously “speaking in the first-person singular talking about the first-person plural.” She was telling the story of black America through her own experience, to provide insight to other black Americans, but also as an act of communication with other groups, including white people. Angelou’s truth, for much of her life, was embedded in an unthinkably racist society. Of course she didn’t fixate on their flaws and of course she drew out their strengths. White people lied about black people, perpetuating stereotypes and practises that continue to tear at American society today. The prevailing narrative was pitched dramatically against her community, so she pushed in the other direction.

What’s more, as well as showing us pain that in fiction would be unbearable, by having the courage to write memoir, Angelou also shared hope that in fiction would be implausible.

It’s worth noting, I think, that although they now seem like figures from a distant past, both Malcolm X and Martin Luther King were contemporaries of Angelou’s; Malcolm X was three years older and Dr. King a year younger. The violent brevity of their lives — among many other black men and women — may distort our understanding of how much has changed in 80 to 90 years. Although extreme and insidious racism survives, within the natural lifespan of Angelou’s generation, black Americans have dramatically forced back the tide of prejudice. Her hope may have appeared implausible, but she was right to hope.

The caged bird sings

with a fearful trill

of things unknown

but longed for still

and his tune is heard

on the distant hill

for the caged bird

sings of freedom.

Image Credit: Wikipedia