While on a tour of an aircraft carrier hangar bay led by a Navy Commander, Geoff Dyer writes: “I always like to be in the presence of people who are good at and love their jobs.” This is the overarching feeling one gets from reading Another Great Day at Sea, in which every person Dyer meets either loves their job or passionately loves their job. It also describes the experience of reading this book. A unique and compelling stylist, and a charming reporter, Dyer seems to have an absolute bang-up time on this assignment, and it’s a pleasure to go along with him.

While on a tour of an aircraft carrier hangar bay led by a Navy Commander, Geoff Dyer writes: “I always like to be in the presence of people who are good at and love their jobs.” This is the overarching feeling one gets from reading Another Great Day at Sea, in which every person Dyer meets either loves their job or passionately loves their job. It also describes the experience of reading this book. A unique and compelling stylist, and a charming reporter, Dyer seems to have an absolute bang-up time on this assignment, and it’s a pleasure to go along with him.

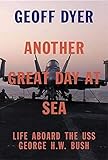

The first book to emerge from Writers in Residence, a new grant organization that sends writers and photographers to report from the “key institutions of the modern world,” Another Great Day at Sea is an account of Dyer’s two weeks aboard the USS George H.W. Bush, the largest aircraft carrier in the world, in fall 2011. Knowing Dyer only from his writing on travel, jazz, and Russian film, I was curious as to why he’d asked for this project, but I quickly learned that from boyhood he’d been a bit of a military geek, and two weeks on the boat brought that out of him again.

Any critic will tell you that there’s nothing harder than writing a thoroughly positive review — the superlatives start to pile up and devalue each other pretty quickly. What I found most remarkable about this book is that Dyer’s uniform delight with everything and everybody he meets never gets monotonous. Every person he interviews is polite, extraordinarily competent, and unfailingly devoted to the Navy, and yet they each come across as unique, interesting people rather than military clones. This may have a lot to do with what Dyer calls his “knack for idiotic pleasantry, anchored in zero knowledge” that draws them out, or the fact that people could probably tell how impressed he was.

“People sometimes talk of feeling ‘humbled,’” he writes, “but that’s not how I felt on the boat; it was more like an awareness of frequently being in the presence of superior individuals whose capacities and experience were quite unlike those I came across — I knew plenty of writers and artists — back at the beach.” (“The beach” is carrier jargon for the mainland. Dyer loves the jargon.)

Dyer’s main objective is that of an anthropologist — cataloguing from top to bottom the workings of this floating mini-civilization of high-achieving sailors. There are chapters on the gym, the toilets, the smoking area, the dentist, the chapel, the brig, the ship psychiatrist, movie night, the pilots, the captain, and the commander of the flight deck. Most of which, again, are to his liking.

But while he scrupulously details the daily life of the carrier, he never comments on its purpose. He talks about the planes taking off and landing every day from their location in the Arabian sea, but never what they’re doing on their flights. Describing a statue of George H.W. Bush, the boat’s namesake, is one of two times politics comes up. Although he admits to being surprised by the fact, he never notices any tension along racial, gender, or sexual lines. As he says, it’s “a happy ship.”

His only source of chagrin aboard the carrier is the prevalence of evangelical Christianity, a fact he delves into when he learns that the lieutenant commander in charge of the flight deck is leaving the Navy, after 28 years, in part to help his wife homeschool their children. Their ensuing conversation — the other time politics comes up — sticks in Dyer’s head, and he expounds a bit on the ship’s preponderance of “religious nuts…an America I had not come across before, an aquatic version of the Midwest and the bible-belt South.” It’s the only time, apart from when he ecstatically receives a free cleaning from the ship dentist, that his British shows. He seems more unsettled by having met conservative Christians than the fact that they sometimes shoot at things from planes.

On the whole, his attitude towards the sailors on the carrier is awe and respect mixed with a little jealousy. They have a clear purpose, and they pursue it with a near-perfection that sometimes leads them into the sublime. When he is interviewing Disney, a young pilot who likens flying to playing video games, Disney says that flying on a clear night over water feels like flying in deep space.

Dyer writes: “So there it was, still intact despite the technological advances and laconic delivery: the lyricism of night flight as first and famously evoked by Saint-Exupéry. It was as if he had revealed something intimate to me, the experience that was at the core of his being: a realm of poetry accessible only to those whose world-view is based on technology, knowledge and calculation rather than wide-eyed wonder…And Disney, the kid who’d excelled at video games, for whom it all came down to hand-eye coordination, on keeping an eye on the dials and switches and the data, was having the transcendent experience craved by mystics, shamans, seekers and acidheads.”

Photo by Chris Steele-Perkins