I wonder

why I am enjoying being so invested in this show

because I wouldn’t say it’s making me happy, per se-my friend L, from a gchat during the 11 days that Sherlock was back on the air

[Don’t worry: there are no concrete spoilers for any of Sherlock series 3 here.]

Last week I published a piece here about the history of Sherlock Holmes, and about how it’s contextualized by the new series of Sherlock — or maybe it’s the other way around. I went through a number of books and scholarly articles and revisited the original stories and put together a measured argument. I had the good fortune to be able to attend the premiere at the British Film Institute with other journalists in December, and I watched all three episodes over the past few weeks with a critical eye, studying the reactions of the British press as each of them was aired. I discussed the essay with writers and editors, working to maintain a cool, judicious distance from the source material. I put together a long, (hopefully!) thoughtful piece that I was proud of, and one that I hoped did Sherlock, and Sherlock Holmes more broadly, some justice.

This, then, is the B-side. “Diary of a Crazed Fangirl.” That’s reductive, though, and perhaps even a bit sexist. “Diary of a Reasonably Intelligent Adult Woman Driven Slightly Insane by a Television Show She’s Grown Attached To.” Maybe I should just lift the best line from my friend L’s inadvertent chat-poem, and call it, “Sherlock: I Wouldn’t Say It’s Making Me Happy, Per Se.”

This is the story of one person in one fandom, but it’s likely got hints of your story, too, if you’ve ever been involved in this sort of thing. I’d hope that it resonates if you’ve ever really loved something that you haven’t created — the I’d-kill-for-you kind of love of a work of art that inspires others to say things like, “Whoa, whoa, slow down, it’s just a book.” I’ve written about fandom, specifically fanfiction, here before — twice, actually. First, to try to debunk the general “anthropologists discover a wild tribe of porn enthusiasts on the Internet” tone that accompanied approximately 90 percent of the Fifty Shades of Grey coverage that mentioned the series’ origin. Second, to try to debunk the idea that Kindle Worlds, Amazon’s commercially-licensed fanfic project, was anything that literally anyone in fan communities actually wanted.

I actively joined the Sherlock fandom only a year ago — and when I say actively, I mean I officially left my previous fandom (it was dying, quickly — the show was over and the smartest voices were moving on — and besides, I only have space for one fandom at a time in my brain and/or heart) and embraced the show full-on, allowing it to colonize my tumblr dash and AO3 bookmarks page and a fair portion of my idle thoughts. In the beginning, it can be a bit like a new relationship — you hope to find a way to slip it into conversation with your friends, and then realize too late that you are bringing it up way too often. (This happens, too, when I work on original fiction; stories are stories, and if the characters get you, you’re done.) I have been joining the fandoms of various books and television shows since the ’90s. I know how this works. And I knew the exact moment I was stepping into something dangerous with this one, because falling for a show with three episodes every two years does terrible things to your mind.

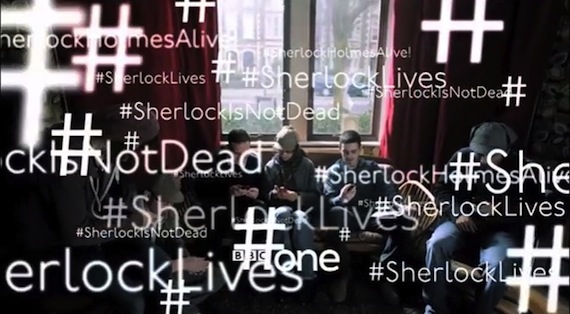

There’s a special kind of desperation that unifies hardcore Sherlock fans, and you can see it in the speed at which memes turn silly — there are only so many times you can go over every scene of a six-episode run with even the finest-toothed comb. You talk yourself in circles; you build wild headcanons based on slivers of hints from the writers — two men who’ve stated outright that they often lie to throw people off the scent. This is all part of the fun — the miserable, miserable fun. The cast and crew appear to be hyper-aware of the obsessive interest — and that’s unsurprising, because after all, Sherlock is helmed by Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat, a pair of men so obsessed with both the stories and the long century of paper and screen adaptations that their Sherlock Holmes fanfic is the show itself. The BBC capitalize on the “event” culture, in Moffat’s words, that’s grown around the show — there was a wild morning in November when fans were, at the bequest of the show’s creators, scouring the streets of London for…something. (In the end, it was a hearse, an ‘empty hearse,’ with the air date of the premiere spelled out in flowers, driven past key locations from the show. I stopped by one of the waiting points, the North Gower Street stand-in building for 221B Baker Street, on my way to UCL. When I had to leave after 15 minutes, I felt a strange sense that I was betraying something.)

By some stroke of miraculous luck, my professional life and my fan life physically intersected in the final weeks of the year. I managed to get a press invitation to the premiere, and had a mild heart attack as I was checking in and saw Stephen Moffat’s curly head gliding past a long queue of deerstalker hats — fans who’d been waiting for return tickets, some of them, it was rumored, since the night before. At the pre-screening reception, I made a friend, a financial journalist about my age. “I really love this show,” she told me. I nodded vigorously. “But I would never wait all night to get a ticket!” she went on. My vigorous nodding slowed to a gentle bob. Would I? I’d considered it. But I had taken an easier option because that privilege was available to me.

I looked around the room and puzzled at this collection of people. We were journalists; we were fans; perhaps we were that kind of fan, but we weren’t announcing it. This complicated dynamic would carry over into the post-screening Q&A, where Caitlin Moran (whom I generally love, incidentally), engaged in a classic Moran-style fuck-up, forcing Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman to read a passage from a John/Sherlock fanfic. It wasn’t particularly explicit but it was romantic and sexual, to be certain, and it was abundantly clear that neither the actors nor anyone in the audience — including those of us who read this stuff in our spare time — wanted this read aloud onstage. She apologized profusely, but the incident set the tone for the strange interplay that would mark the weeks that followed, between the show’s makers and its fans, from casual to hardcore, and the critics observing and trying to explain what they didn’t fully understand.

The three episodes aired over the span of 11 days here in the U.K., each of them pulling in about a third of the British viewing public and millions more abroad, through legal means or otherwise. Moffat wanted an “event,” and he got it, three times over. It felt like every British person on my Twitter feed had a 140-character review. Public opinion appeared to sway wildly from week to week, and newspapers seemed to be hunting for controversy, publishing positive reviews and then countering them with takedown pieces, highlighting the most polarizing voices and muting more nuanced views. They do that with everything these days, you say. They’re just looking for clicks. Yes: we are in agreement! But there is something to be said for placing so much anticipatory weight on a television show: nothing can be all things to all people, and Sherlock felt smothered by the weight of nine million expectations. Tons of people loved it, and were put off by negative criticism; tons of others threw up their hands and said, “This is not what I signed up for. This is not my show.” Others still urged people to calm down: it’s just a TV show after all. But to say this diminishes the importance of storytelling in our lives, in whatever mode. It’s hard not to get invested in stories, and in characters, that we love. That’s what people do.

As a critic and as a person who wants to see this show continue to be made, I felt I had a vested interest in the critical and public reactions, respectively. But at my core, I am a fangirl. I read and write fanfiction (never published; I hate WIPs), and I obsess. I’ve always obsessed. A lot of fan activity these days happens on Tumblr, and the Sherlock community there fractured around divided opinions, too — though they somehow never managed to align with those of the rest of the world. We all want different things from the things we love; we’re all inevitably disappointed in some way. Mixed reactions in fan communities are par for the course — transmedia scholar Henry Jenkins pinpointed something key when he wrote that “fan fiction emerges from a balance between fascination and frustration.” One of the biggest criticisms leveled at Sherlock’s writers this time around was an accusation of “fan service” — that the fourth wall was being pecked away at, sometimes outright shattered, and elements were added with a knowing eye focused on fans, particularly the “vocal” group that the show has attracted. Within the fandom, some fans agreed and took this accusation to heart, while others felt they weren’t being serviced enough, or at all. Emotions ran high, and vitriol sprung up; I spent 11 days feeling far more tense than I should have. I took long walks along the Thames, and even went to church a few times to clear my head.

(It’s worth noting here that a lot of fan communities are most vocally female, and I don’t think that the Sherlock fan community is any exception. It felt like there was a special criticism being leveled at female fans of Sherlock, “silly fangirls,” that sort of thing, dismissed as a group of people who like watching Benedict Cumberbatch ruffle his hair (c’mon guys, this is clearly all humans, ever) or people who welcomed the fair amount of screen time being devoted to character development in these three episodes. Somehow these were female desires being imposed, despite the three men writing the scripts. There’s an analogy in here to modern fiction, in men refusing to read books marked as feminine in some way, that sort of thing, but I can hold onto that one for another day.)

I’ve always been a lurker — eager to consume fan works and conversations but hesitant to join in. This time around, I was joined by two fellow lurkers, “R” and “L,” friends from college who love the show but have mostly kept their spiraling meta-analyses inside their heads. We let it all out, the kind of avalanche of analysis and reaction a lot of us have after reading a book or seeing a movie with friends, but for days on end. We had a lot to say: thousands of words across nearly a hundred emails. We all process stories by talking them through, trying to balance rationality with emotional response. We scrutinize; we flail and squee. And in our little group of three, we split. R, the one who’s been with the show the longest, wavered, hating most of the first two episodes but finding more to like about the third. In the end, she walked away wholly disheartened with the show. “There were absolutely lots of great scenes in this series but to me they don’t fit together,” she wrote in one of her final emails. “And though I’m inclined to try and rationalize I don’t know if there’s a point because the heart of it is that I just don’t trust the showrunners anymore.”

L and I wound up on mostly the same page: largely happy with the show but fairly unhappy with all the dissatisfaction and the unending dissections. The normal pains of absorbing new material were amplified by the speed at which the series aired, and the length of the episodes themselves. It was tiring: I wrote, on the eve of the finale, “Oh God I just want tomorrow to be over so I can stop having a mild heart attack and we can get back to fanfiction.” I was looking for someone to make sense of it all, and had the good fortune to come across Anne Jamison shortly after the first episode aired, via some very smart women who write some very smart fanfiction, and, I learned and shouldn’t have been at all surprised to see, some very smart critiques (aka meta) of the show.

Jamison is an academic who participates in the Sherlock fandom, amongst others; her latest book, Fic: Why Fanfiction Is Taking Over the World came out late last year. I got my hands a copy and promptly devoured it. It should be noted that, post-Christmas 2013, this is the first book I’ve actually fully read in electronic form; is it that experience, or something in way it is written and pieced together (guest contributions interwoven with a strong, linear narrative from Jamison herself) that makes it feel very new? I’m liable to say it’s the latter — she writes in the introduction: “The desire to host this conversation leaves Fic somewhere between monograph and edited collection. It might help to think of it as a tour through a curated exhibit that I’ve arranged and guided and shaped.” It’s also likely that the subject matter has a hand in this: Jamison writes of fanfiction working in many directions, from the traditional author/reader relationship to more lateral connections, fanfic writers and readers working across genres and preferences and even source material to create webs based, above all, on taste: what we want to read, and love reading, a vast network of influences and references and experimentation and quick, constructive feedback. A utopia — sometimes. At the very least, a way of sharing stories that feels refreshingly organic, and one that continues to evolve — in fascinating ways — with technological shifts in communication.

Jamison is an academic who participates in the Sherlock fandom, amongst others; her latest book, Fic: Why Fanfiction Is Taking Over the World came out late last year. I got my hands a copy and promptly devoured it. It should be noted that, post-Christmas 2013, this is the first book I’ve actually fully read in electronic form; is it that experience, or something in way it is written and pieced together (guest contributions interwoven with a strong, linear narrative from Jamison herself) that makes it feel very new? I’m liable to say it’s the latter — she writes in the introduction: “The desire to host this conversation leaves Fic somewhere between monograph and edited collection. It might help to think of it as a tour through a curated exhibit that I’ve arranged and guided and shaped.” It’s also likely that the subject matter has a hand in this: Jamison writes of fanfiction working in many directions, from the traditional author/reader relationship to more lateral connections, fanfic writers and readers working across genres and preferences and even source material to create webs based, above all, on taste: what we want to read, and love reading, a vast network of influences and references and experimentation and quick, constructive feedback. A utopia — sometimes. At the very least, a way of sharing stories that feels refreshingly organic, and one that continues to evolve — in fascinating ways — with technological shifts in communication.

The resulting portrait of the long and varied history of fandom — with a specific emphasis on fic, and, oh, what a delight to see some fanfic I’ve read and loved analyzed like any other good work of literature — is a picture of the wide-open spaces in between. Books and television shows and movies inherently leave gaps; whether we choose to linger over them, to explain them away, or to work fill them in, is our right as consumers of art, and as fans. But it’s easier to see what fans get from the creators of art than what they really deserve. I wrote to Jamison and asked if she could help me puzzle out what had happened with Sherlock series 3: why was it so divisive, and what about the fans in all of this? What did she think of the ideas about challenges to the fourth wall?

“From my perspective — viewing Sherlock as a very high quality, very clever, very well-written fan work — this show has always challenged the fourth wall,” she wrote in response. “Their mission statement is to mess with canon and to redefine it as inclusive — if they feel like it. They are not writing the kind of reverent, in-universe missing case or missing scene pastiche that has long been popular with Sherlockians.” Throughout the episode-run, there was so much talk about how the show had changed — and those who didn’t like those changes insisted it was for the worse. Jamison draws up what I think is a great analogy: “If you *loved* the early Beatles, there’s no guarantee you’re going to love Abbey Road, because the band had gotten to a very, very different place musically and personally. I don’t think it’s unreasonable of people to want more of what they love, and not to have it change…But obviously, there were more Beatles fans who were happy to see the band grow and go in new directions, even if they preferred some over others. And that’s exactly what happened with Sherlock.” She continues:

I think Sherlock *is* fanservice but I think that the creators themselves are the fans they are servicing. They couldn’t make this show if they weren’t incredible Sherlock Holmes fans. Sherlock is in the enviable position of being event television that people will tune in for. They can afford not to play it safe. By going over familiar ground — with Sherlock Holmes — and by doing so few episodes, they buy the opportunity to do very new things in television. Just like fanfiction writers always do — people will tune in for the characters and read something more experimental than they might otherwise because there’s enough there to make them feel at home.

Jamison helped me sort out some of the thorniest bits that lie at the heart of the show’s specific problems in relation to its fans — there are gendered issues at work here, for one, questions of representation, perhaps reasons why the broader universe is ripe for those coming from, and looking for, the spaces in between. (“I think your sense of gender discrimination, though, and gendered storytelling, is spot-on,” she wrote. “Part of the problem is that somehow narratives about feeling have become coded as feminine. That wasn’t the case in [Arthur Conan Doyle]’s day.”) We’ve put the full (long) conversation up over on her tumblr if you’re interested. Funnily enough, while we were exchanging e-mails, an incident similar to the Moran fanfic fiasco cropped up, this one concerning Amanda Abbington, the cast’s newest regular, and her objection to fan art depicting her partner, Martin Freeman. Jamison has smart things to say on that, too.

The Hiatus has begun again, and the British public has moved on with their lives. Hell, they probably moved on the Monday after the finale aired, perhaps after a chat at the proverbial (or literal? Is that still a thing?) water cooler. (The Daily Mail wrote an amazing blustery article that morning saying Sherlock was full of liberal bias, and we all had a much-needed laugh.) It’s been a few weeks now, and the fans remain, because fans always remain, and will continue to turn over the text in new and surprising ways. Some people have abandoned the show, I’m sure, but new fans are probably tentatively stepping through door as I write this. People will try to explain away their confusion, and if they can’t rationalize it, well, they can fix it, too. The fanfiction has begun. I feel less of a need for long, drizzly walks along the Thames — at least not for this stuff, anyway — though I am slightly wary about going through another round of “event” television again. On the other hand, I really cannot wait to see what’s coming next. I certainly cannot wait another two years. Please, please, for the love of God, not another two years.

About a week ago, my friend L sent a beautiful meditation on the meaning of the show in her own life, which, after all of this, she still loved — with reservations, of course.

Spending time thinking and writing about Sherlock is on one level a form of escapism. It’s a place where I can let my mind do some gymnastics while I’m waiting in line at the bank or washing the same cup for the hundredth time at work. But it’s not just any place where I’m mentally doing just anything. In the tradition of the science fiction and fantasy novels that I love best, Sherlock deals with a lot of ideas and issues in a manner that is indirect enough that it is not obvious and preachy, yet they are still realized in a compelling way…Certain lines or plot points act like catalysts for things that are already going on in my head. Much of it comes from the magic of these characters, the Sherlock Holmes and John Watson that have endured and been re-imagined and reinvented for over a century. A lot of it comes from the universe created by Moffat and Gatiss, and still more from the combined chemistry and individual performances of Cumberbatch and Freeman. For whatever reason, I find that this environment is a wonderful place to grow the seeds of these big thoughts in the semi-privacy of my own brain.

I get invested in this stuff too, certainly; fictional characters from both high and low culture have always occupied prime seats in my mind (palace). In the end, these are just stories, which is what we’re after most of all, I suppose — a way to contextualize our own stories, the ones we tell ourselves to make sense of things. Anything that’s both beloved and serialized has to deal with the disconnect between the stories that its creators want to tell and the stories that fans, from the casual on up to the obsessive, want to see. For me, I suppose it’s like any addiction — I’m so grateful for everything we get, and then, when the dust settles, I just want to see more.

There is a weirdly fitting coda to all of this: I was working to finish this essay in a coffee shop in Central London a few evenings ago, and my computer’s battery ran out just as I typed the word “showrunners.” I sighed and took off my headphones and shut my laptop. And then I heard a very familiar laugh: I looked around and did a genuine double take, because Mark Gatiss was sitting about 10 feet away, chatting with a friend. I tried not to freak out. I was paralyzed: a devoted fan and the creator of said fan’s interest just a few feet apart in a random café and where the hell was the fourth wall (made of impenetrable brick) that I needed to keep me from rushing over and making a fool of myself? I didn’t, don’t worry. Too shy or too scared, or maybe, to put a more positive spin on it, too considerate of a private individual having a conversation to interrupt. After he left, the man at the next table turned around and said, “Was that Mycroft!?” So much more than that, I wanted to tell him. I nodded instead. There’s a metaphor in all of this, somewhere.