After a long career in behavioral neuroscience, I became a science writer and writer of fiction — not, however, a science fiction writer. As the author of a debut novel, I was advised not to mention my science background because it might put readers off. What, after all, about science would recommend one as a writer of fiction unless it was science fiction? For an answer, I look no further than the man with the bandaged head.

When I met him, he was sitting up in a hospital bed, his head and half his face encased in bandages. Young, handsome, unshaven, he looked like a veteran of a long-ago foreign war. He gesticulated frantically, wild with focused desire, his exposed eye imploring and bloodshot. His broken words and phrases sounded like Greek to me, and in fact were Greek. As was he. I was as desperate to understand as he was to explain.

He’d come in the previous night through the emergency room, without identification. It was part of my job at the hospital — a job I’d taken in my 20s while figuring out who I was — to figure out who he was. It was 1972. Google wasn’t a word let alone a verb, and copies were not “made” but typed. In triplicate. Sorting out the John and Jane Does — the homeless, the brain-damaged, the overdosed, the mentally unstable — meant calling phone numbers written on the backs of matchbooks, chatting up bookies and pimps, and sometimes getting lucky and turning up a relative or friend.

I’d become quite an expert at communicating with those who could barely speak or made little sense when they did. The hospital was pleased — identities and financial status revealed. End of story. But not for me.

The man with the bandaged head resorted to pantomime, forming a curvy silhouette with his hands. “Girl?” I said, stepping closer. He nodded vigorously, apparently able to understand some English. He slapped his hands together with a sharp crack, and lolled to his side. Then shot me a glance to see if I got it. “You were mugged,” I said. I knew he had been. He groaned in frustration and pointed to his leg then gestured the breaking of a stick. “Broken leg?” I asked. His leg was not broken, but he nodded yes. Made the silhouette again with his hand. “A girl with a broken leg?” He sank back and fluttered his fingers over his heart. “She was with you last night,” I whispered. Tears eked out from the now closed eye. “I’ll try to find her,” I told him. He clasped my hand.

The man with the bandaged head communicated without language, and I never forgot him. Years later, in the midst of a 25-year career investigating neurologically based communication disorders, my research would focus on a subset of right hemisphere brain-damaged adults in whom speech and language were preserved, but for whom the non-linguistic aspects of communication were impaired. These were people for whom language had a one-to-one correspondence with words, but who failed to draw inference, were insensitive to implied meanings, unresponsive to context, absent of questions. Looking at a picture of family on a farm, racing against the wind to an in-ground storm shelter, they might name every element in the picture right down to the storm clouds, but fail to integrate them with the shelter, the frantic action, and fearful expressions to conclude that a tornado is imminent.

With its objective, systematic measurement and testing of empiric phenomena, its carefully controlled steps, its literal, constrained language, science appears at odds with the often chaotic, unbound, subjective mind-set brought to bear in writing fiction. Yet, at the intersection of the known and unknown, the best science has a foot in a fictional world for what is an experimental hypothesis but a speculation on the story to come and how it will play out? And the best fiction requires linguistic precision and a scientist’s eye for detail. But there the similarities do not end, for both neuroscience and fiction ask the fundamental human question: who are we?

Experimental or mainstream, irrespective of genre, literature asks what motivates us, moves us, connects and separates us? Neuroscience asks not just how the brain works, but the mind as well. We’re not just an assembly of neuronal, neurochemical, and molecular actions transmitting electrical signals throughout the brain. True, we can now mimic those signals through externally generated electrical pulses to improve hearing, make a limb move, or stop tremor. But we cannot yet simulate cognitive experience, our sense of ourselves, of being.

The better the science, the more new questions it generates. So, too, with fiction. An eloquent description right down to the porkpie hat and mole on the left cheek will lie flat on the page unless those details reveal character, propel the story. If you don’t engage the reader’s mind, allow the reader to draw inferences, ask questions, the story will die. The six-word story attributed to Hemingway, “For sale: baby shoes, never worn,” is famous for the wealth of questions it suggests, the unspoken context it evokes.

It wasn’t the name written in triplicate that told me who the man with the bandaged head was. It was his story — how he’d just landed in this country, the girl he’d met that night, the walk they took, unsuspecting, in a risky neighborhood, how they had communicated through his broken English about their dreams, their hopes, the “who” of who they were.

How the brain transforms the firing of neurons into thought, memory, and self remains a mystery. Like the independent life of stories transcribed to the page by the writer, transformed, reconfigured, kept alive by what readers breathe into them, the mystery keeps us alive with wonder. And wonder is a source of our humanity and our hope. The day after my conversation with “Christos,” transport wheeled a young woman with a broken leg into his room. “Man with bandaged head finds girl.”

I leave the rest of the story to you.

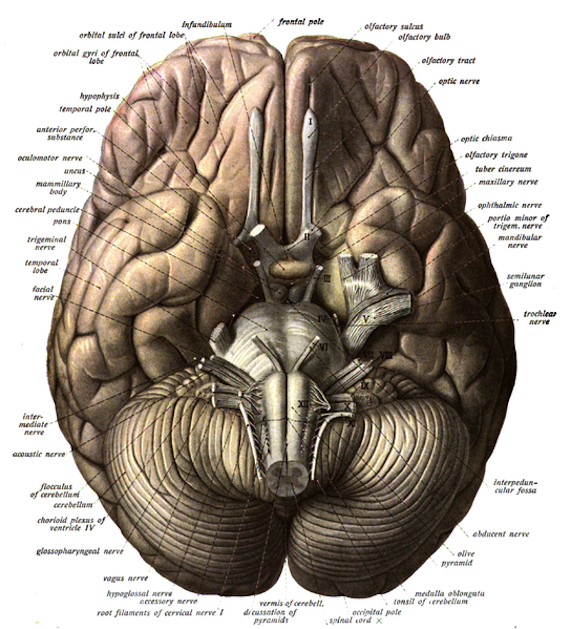

Image Credit: Wikipedia