This piece was produced in partnership with Bloom, a site that features authors whose first books were published when they were 40 or older.

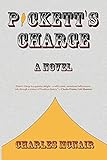

Charles McNair’s strange, frequently beautiful new novel Pickett’s Charge is about an old Confederate soldier who embarks on a journey from Alabama to Maine looking for vengeance. I received the book in the mail just as I was beginning a nearly opposite journey — though for work, not blood — and I picked it up hoping that the story would help me begin to understand a unique part of the country I’d soon be calling home.

Charles McNair’s strange, frequently beautiful new novel Pickett’s Charge is about an old Confederate soldier who embarks on a journey from Alabama to Maine looking for vengeance. I received the book in the mail just as I was beginning a nearly opposite journey — though for work, not blood — and I picked it up hoping that the story would help me begin to understand a unique part of the country I’d soon be calling home.

The South, more than any other region of America, is forbidding to outsiders. I watched two kids from my high school class attempt college in the South before retreating back to Maine within a year, which left me thinking maybe it was never wise for New Englanders to stray into such unfamiliar territory. More generally, I grew up with what I take to be a somewhat common perspective, on the South as charming but inscrutable, languid but dangerous, a place where sinkholes — real and metaphorical — await anyone who doesn’t know exactly where to step.

Even for natives, apparently, the South is perilous. When Pickett’s Charge opens, Threadgill Pickett is a magically spry 113-years-old and living in a nursing home in Mobile. Everywhere he goes he wears a gray cap with a faded yellowhammer feather, a holdover from his brief, terrible stint as a teenage soldier in the Rebel army. The hat covers horrific burns that melted Threadgill’s head down nearly to the gray matter, and it covers other wounds, too, like the memory of his twin brother, Ben, being executed by vicious Yankee soldiers. The scars on Threadgill’s head reflect the anger and shame scarred into his heart. One wonders whether McNair means for Threadgill to reflect the state of the South, too, a century after its final surrender.

Threadgill is idling in the nursing home when Ben drops like an apparition into his room with an important message. “Ain’t but one Yankee left now, Gill. Just one. He’s up in Bangor, Maine…You hearing me? Hear what I’m saying?” Ben says. Provoked, Threadgill sets off on an assassin’s quest to avenge his brother’s death, during which he has a bewilderingly imaginative range of Southern adventures — with a lesbian cab driver, a mad monkey smuggler named Larry LaRue, a midget passing a kidney stone, and an island populated only with goats.

Pickett’s Charge is filled with phantasms, but it’s rooted in Alabama soil. Charles McNair, 59, grew up in Alabama, and has written just one previous novel, Land O’Goshen, which was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in 1994. His virtues as a writer are plain. He’s inventive, original, and has a particular talent for finding language that is surprising without being showy. But his real skill is his deep familiarity with the South as a place, it’s creatures, customs, and yearnings.

Pickett’s Charge is filled with phantasms, but it’s rooted in Alabama soil. Charles McNair, 59, grew up in Alabama, and has written just one previous novel, Land O’Goshen, which was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in 1994. His virtues as a writer are plain. He’s inventive, original, and has a particular talent for finding language that is surprising without being showy. But his real skill is his deep familiarity with the South as a place, it’s creatures, customs, and yearnings.

For example, alone on that goat island, Threadgill puts his foot down on “something pulpy,” and instantly realizes what “[e]very boy raised in the South knows,” that he’s just stepped on a deadly cottonmouth. Elsewhere in the story, a tornado rips through a poultry farm, leaving behind tens of thousands of dead chickens, which sets the stage for a grand barbecue like a heavenly feast. It’s a fantastic setup, but McNair fills it with knowing details — “Men wore muleskinner gloves to drag the hot tin. Crews with pitchforks spread the chickens into cardboard boxes” — that conceal the edges of the myth.

From a national view, the South is still a place of myths and larger than life characters: Bible thumpers, Tea Partiers, Creationists, secessionists, vote suppressors. The biggest mythology of all, though, is about race and the idea that 150 years after what is generally referred to as the Civil War, the South remains insufficiently repentant about the place that slavery and racism occupy in its cultural heritage. You can’t spend five minutes in the South without beginning to look for evidence of the myth in practice, without seeing in every interaction between a black cashier and a white patron, a direct extension of that peculiar institution.

Pickett’s Charge is not about race, and Threadgill’s hatred for the North overwhelms any particular views he might have about people with darker skin than his. Nevertheless, his murderous quest is bound up with the South’s racial legacy. At one point he finds himself at night in a forest filled with wailing black men and women, whose backs are striped with scars. Later, he witnesses the last act of brutal murder, a black preacher’s body tossed into a river.

You keep waiting for all the violence and strangeness to knock Threadgill off his mission. In such a bizarre, capricious world, surely one man’s single-minded effort to kill the last remaining Yankee soldier must be folly. McNair is an expansively generous writer — attentive to his readers and kind to his characters — and he carefully avoids reducing Threadgill to an object of pity. But he does suggest that Threadgill’s deliberate course north is misguided, just as many attempts to find the edges of a myth are likely only to lead you deeper into the swamp.