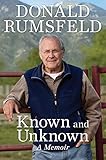

Donald would’ve been an easy book to get wrong. After all, when McSweeney’s announced in early January that it would release Eric Martin and Stephen Elliott’s “high-wire allegory” on the same day as former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld’s memoir Known and Unknown, the message seemed clear – Rummy is about to get waterboarded.

Donald would’ve been an easy book to get wrong. After all, when McSweeney’s announced in early January that it would release Eric Martin and Stephen Elliott’s “high-wire allegory” on the same day as former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld’s memoir Known and Unknown, the message seemed clear – Rummy is about to get waterboarded.

And, some would feel, rightfully so. To many, the lines crossed by the United States in the War on Terror were not fine but coarse, and although the former administration has moved on, the ire it incited remains. But rather than exploiting this obvious emotional peg, Martin and Elliott take the high road. Donald is a smart, subtle story that provides new insight into a man at the center of it all.

The plot is roughly what you’d expect. After a day of research and an evening out with friends, Donald, a former senior government official, is abducted from his study while his wife is upstairs. A team of masked gunmen hood, bind, and drug Donald, who later wakes up in a cell where he is subjected to oblique interrogations. This routine is repeated a few more times, as Donald is shuffled through a disorienting system of temporary prisons. But if bloodthirsty Rumsfeld-haters are hoping for a good killing here, they’ll be disappointed. Yes, Donald gets a bit roughed up. But he’s never waterboarded and you won’t hear him beg for mercy. This isn’t a literary flogging.

Critics and columnists alike have knocked Known and Unknown for the gaps it reveals in Rumsfeld’s character. In a recent column, Maureen Dowd said that the memoir, “is like a living, breathing version of the man himself: very thorough, highly analytical, and virtually absent any credible self-criticism.” The Times’s reviewer Michiko Kakutani added, “It is a book that suffers from many of the same flaws that led the administration into what George Packer of The New Yorker has called ‘a needlessly deadly’ undertaking — that is, cherry-picked data, unexamined assumptions and an unwillingness to re-examine past decisions.” Martin and Elliott somehow anticipated those gaps, and they fill them in with Donald. In the opening scene of the novel, a young man and woman confront Donald in a library over his testimony in a commission’s report. “There are omissions in your account,” he says. “We’re looking to set baselines for productive dialogue.”

In the end, productive dialogue with Donald is impossible. But it’s hard not to root for the guy a little when he’s abducted. His pluck and tougher-than-thou ethos, his old-school self-reliance, and the tenderness with which he expresses his love and concern for his wife almost render him sympathetic. But these impressions fade as Donald’s true character inexorably emerges over the course of the novel.

His blind ambition and arrogance are highlighted when he considers overtaking his captors by force, mano a mano. Donald can’t see that the wrestling instincts of his youth now inhabit the 78-year-old frame of a retired bureaucrat. His love for his wife morphs into a kind of grotesque solipsism as he ultimately uses her voice to reminisce about their relationship in his prison scribbling. The fact of his doing this is not that bothersome. What’s disturbing here is the way he does it.

The bottom line is I never would have married anyone until he married someone other than me. I’m sure he would have liked to live the bachelor’s life for a few more years. But he thought: Gee, I’m not going to wake up someday and say why didn’t you act faster or sooner. So it was more of an intellectual decision, not knowing that I would have waited. So the fact that we were engaged was just a big surprise to everyone. It’s not that there wasn’t passion. Of course there was. But it was always a lifelong partnership.

One night, late in his captivity, the questioning young man from the opening scene in the library returns. He stands outside Donald’s cell, presumably waiting for that productive dialogue to begin. Here, what initially appeared to be self-reliance, is revealed to be mean self-righteousness. Donald barks, “These people are trained to lie. They’re trained to say they were tortured. Their training manual says so. We learned a great deal about them. Their methods. Their skill sets. We’ve learned a great deal through this process which has been humane.” The subtext here is clear –“Hey, don’t look at me; these people got what they deserved.”

At a tight 110 pages, Donald is written in gorgeous prose and makes for a hypnotic read in one sitting. As Donald dines with his wife and another couple, their champagne, “looks like ice washed in gold, with perfect beads of bubbles skipping to the surface.” When Donald is abducted, the bodies around him smell, “like leeks and batteries.” “Motes of sunlight dance in his new cell,” when Donald is returned to the general population after a stint in solitary.

The elegant writing coupled with Martin and Elliott’s emotional restraint allows for Donald’s ultimate point to stand in high-relief. When the person chained in darkness is dragged into the light in Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave”, his eyes eventually adjust and a new reality emerges. Perhaps because he is too confident in his own perception of things or simply a relic of a simpler time, Martin and Elliott’s Donald is incapable of such adjustment. He is blinded by the realities of the world in which he finds himself.