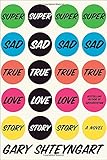

“Oh, dear diary. My youth has passed, but the wisdom of age hardly beckons. Why is it so hard to be a grown-up man in this world?” Bemoaning his fate thus is 39-year-old lovable loser Lenny Abramov, the bookish and neurotic Russian-Jewish-American protagonist of Gary Shteyngart’s feverish, boisterous, wildly funny yet also contrived and histrionic new novel: Super Sad True Love Story. And Lenny’s philosophical lament, equal parts rueful and self-deprecating, does not begin to encapsulate his troubles. The not-too-distant future world in which he feels himself an anachronism is a place generally negotiated with the aid of an äppärät, an electronic communication and data-collecting device with which Lenny hardly feels comfortable. His need for genuine human interaction instead of the äppärät-generated classification of humans according to everything from their credit to their “Fuckability” ratings, not to mention his preference for books over text-scanning—again courtesy of those infernal all-purpose äppäräts—sets him apart.

“Oh, dear diary. My youth has passed, but the wisdom of age hardly beckons. Why is it so hard to be a grown-up man in this world?” Bemoaning his fate thus is 39-year-old lovable loser Lenny Abramov, the bookish and neurotic Russian-Jewish-American protagonist of Gary Shteyngart’s feverish, boisterous, wildly funny yet also contrived and histrionic new novel: Super Sad True Love Story. And Lenny’s philosophical lament, equal parts rueful and self-deprecating, does not begin to encapsulate his troubles. The not-too-distant future world in which he feels himself an anachronism is a place generally negotiated with the aid of an äppärät, an electronic communication and data-collecting device with which Lenny hardly feels comfortable. His need for genuine human interaction instead of the äppärät-generated classification of humans according to everything from their credit to their “Fuckability” ratings, not to mention his preference for books over text-scanning—again courtesy of those infernal all-purpose äppäräts—sets him apart.

And another thing: the world teeters on the brink of financial ruin. Which is too bad, not least because Lenny has just met the woman of his dreams, fellow confused American Eunice, during a sojourn in Rome, Italy. And he knows it: “For me to fall in love with Eunice Park just as the world fell apart would be a tragedy beyond the Greeks.”

Super Sad True Love Story comprises Lenny’s diary entries alongside Eunice’s text-messages, sent via her äppärät to family members and friends. Intriguingly, such a format enables Shteyngart (who is about Abramov’s age, was born in Leningrad to a Russian Jewish family that immigrated to the United States when he was a child, and has written the acclaimed novels The Russian Debutante’s Handbook and Absurdistan) to explore the versatility of language, whether masterfully employed or scandalously abused. Shteyngart clearly savors the adventuresome possibilities of English, possibilities made nearly infinite in this book by the profusion of infectiously silly youth argot, pompous and pseudo-scientific technical jargon, grammatically convoluted but always colorful dialects, and self-pitying meditations—sometimes uproarious, other times poignant—on the mystery of love and the evanescence of life. Indeed, aside from satirizing the corruption of American society by consumerism and its subversion by militarism, Super Sad True Love Story celebrates the power and beauty of words. Shteyngart endows Lenny—who finds himself in a world considerably more illiterate than our own—with an innocent, almost primordial logophilia: “I relished hearing language actually being spoken by children. Overblown verbs, explosive nouns, beautifully bungled prepositions. Language, not data.”

Back in New York City after his sabbatical in Rome, Lenny resumes work at the Post-Human Services division of a huge and—unbeknown to him—possibly sinister company. His department’s ambitious task is to make eternal human life possible. For Lenny, who suffers from an acute fear of mortality, his work is also very personal. He desperately hopes to qualify for the dechronification and cell-regeneration treatments necessary for immortality, thereby joining his visionary boss Joshie on the road to foreverdom. He may never prove eligible; his credit’s pretty good, but he hasn’t been fanatically monitoring and tweaking his triglycerides and pH levels and whatnot. Still, he has an unrelated reason to rejoice; Eunice unexpectedly moves in with him despite being unsure as to whether to pursue a relationship after their dalliance in Rome. Eunice is 24, Korean American, pretty and petite, and alternately grossed out by and drawn to the shambolic, technologically inept, emotionally cloying, and physically unimpressive guy who’s nuts about her and quite willing to put her up for as long as she likes while she avoids moving back in with her family and abusive father in New Jersey.

It’s in the States that the reader becomes exposed to the full measure of madness hinted at by Lenny’s ordeal at the US embassy in Rome. America, where television seems limited to Fox Liberty-Prime and Fox Liberty-Ultra, has become virtually a police state. The country is governed by the Bipartisan Party, with soldiers of something called the American Restoration Authority patrolling the streets, ready to quell unrest by Low Net Worth Individuals (so-designated because of their poor credit ratings and meager assets) as well as disgruntled members of the National Guard, who are fed up with official neglect at home after having served in a disastrous invasion of Venezuela.

Readers of George Saunders’s novellas and short stories may find the socio-economic landscape of Super Sad True Love Story somewhat familiar, what with the hegemony of corporations and the crazed consumerism of citizens. But Shteyngart charts his own course. The economy, run by gargantuan corporations such as LandO’LakesGMFordCredit, is being bought out by China, itself run by the Chinese People’s Capitalist Party, at whose head sits the all-powerful Chinese Central Banker. Already, yuan-pegged dollars are worth a lot more than the plain old kind. Meanwhile, sexuality has become so commercialized that one can watch a political commentary show the gay host of which interrupts his observations to engage in live sex. And while the United Nations no longer exists, in its place can be found the United Nations Retail Corridor, which features stores such as JuicyPussy (and JuicyPussy4Men) selling transparent onionskin jeans and nippleless bras.

Much of this is quite funny—if over-the-top—in addition to being scathing. Ironically, however, the source of its humor is also the book’s greatest weakness. The broader the satire—and Super Sad True Love Story is pretty broad, even when compared to Shteyngart’s earlier two novels—the more one-dimensional and artificial many of its characters. For example, Lenny’s youth-obsessed boss Joshie, his media-crazed friends Noah and Amy, and, to a lesser extent, his and Eunice’s fathers—his rabidly right-wing, hers motivated almost solely by shame and status—embody societal phenomena rather than the complexities of real people. To be sure, Lenny and Eunice do not fit this mold, what with their delightfully complicated personalities, together with the fact that Shteyngart has neither completely dissociated them from nor submerged them in the respective cultures of their origin. But, to the detriment of the story, they remain surrounded by caricatures.

Perhaps it shouldn’t come as a surprise that, for someone given to frenzied social parody, whatever drama is conscripted for the sake of ballast will be similarly overwrought. Shteyngart’s sense of humor largely abandons him and he begins to take himself much too seriously when, two-thirds of the way through, the story veers toward violence and socio-politico-economic breakdown. Forget dystopia; what we have here is much closer to Armageddon than the atomization of humankind Lenny previously found so soul-destroying. This time, though, it’s the avarice of a privileged and blithely murderous section of humanity, rather than the retribution of a vengeful god, that sets everything ablaze.

Make no mistake. Super Sad True Love Story boasts two tormented but appealing protagonists locked in a deliciously tortuous love affair. It is indeed super sad, though thankfully untrue and difficult to imagine as prescient, while proving by turns incisive and hilariously exaggerated in its skewering of American society’s excesses. But its own excesses, the product of a willfully cynical attitude on Shteyngart’s part toward the future trajectory of American culture and politics, prevent the story from transcending the restrictive confines of satire, and eventually madden and exhaust even the most amenable and patient reader.