I only revise poems on a clipboard. Masking tape is wrapped around the clip, the words “Cross Country” written in marker. My wife used it during her coaching days, and I leave the tape on. Poets are sentimental; it is one of our defining traits.

Poems command a space. They are structural objects. I need to hold them, see their type on the page. Prose can live on the screen for me, but poetry needs to get out and breathe. A poem on a clipboard is a statement: it’s time to get to work.

I learned this method from Erin Aults, a friend from college. We went to a small school on a river where people took writing seriously. I was inspired by how she would revise her poems: she had a clipboard at the library, or sitting around campus, and it seemed like there was a little bit of ceremony to the action. Her poems were wonderful, and she had a great eye as an editor for our school literary magazine, so I trusted her methods. The other defining trait of poets: we believe in ritual and superstition.

Years after college—when memories of then had become a little fuzzy, yet still comforting—I was reading an article about an archive of 30,000 horticultural periodicals at the Royal Botanical Gardens. The project was methodical, and necessary. The catalogs ranged back to 1853. More than simply the story of seeds (although that would be enough, I think), they are the stories of cultures and lives. And halfway through the article, I saw someone familiar: Erin. She’s in charge of the archive.

How does a poet become an archivist? I think I suspected the answer before I asked Erin: you approach objects with care.

I like to see the routes that lives take, and Erin’s has got me thinking about what draws us to poetry—and what we draw from it. She still feels “almost a euphoria about the language and directness of poetry, that it has both exactness and expansiveness.” After college, she worked at a used bookstore in Columbus, Ohio, which began her “love of the book as an object.” She remembers “especially during the heavy ‘buy season’ (usually spring and summer when the public was selling off their books to us), as this grand battle between me and making order of these objects. The backroom and processing area of the bookstore would be overflowing with books. There was a lot of learning how to ‘conquer’ the books as objects either through stacking or ordering or selling.”

Soon after, she was working at the Ohio State University libraries, where she “dissected and mended books and paper, learning their science, understanding materials, form, and outside pressures that affected them.” Later, she handled books of Catholic history at the John M. Kelly Library at University of St. Michael’s College in the University of Toronto. Some texts were from the 1500s, and she was “aware that I am one of so many people who have touched this book, that the book is a perfect machine—moveable parts and all. I understood my purpose as a conservator, librarian, and archivist is to help it last another 500 years and to make sure that people have the chance to work with it and be close to it. This is a piece of history that will not tell you what it contains unless you touch it, move it, and work with it.”

That sounds like the mechanics of poetry to me.

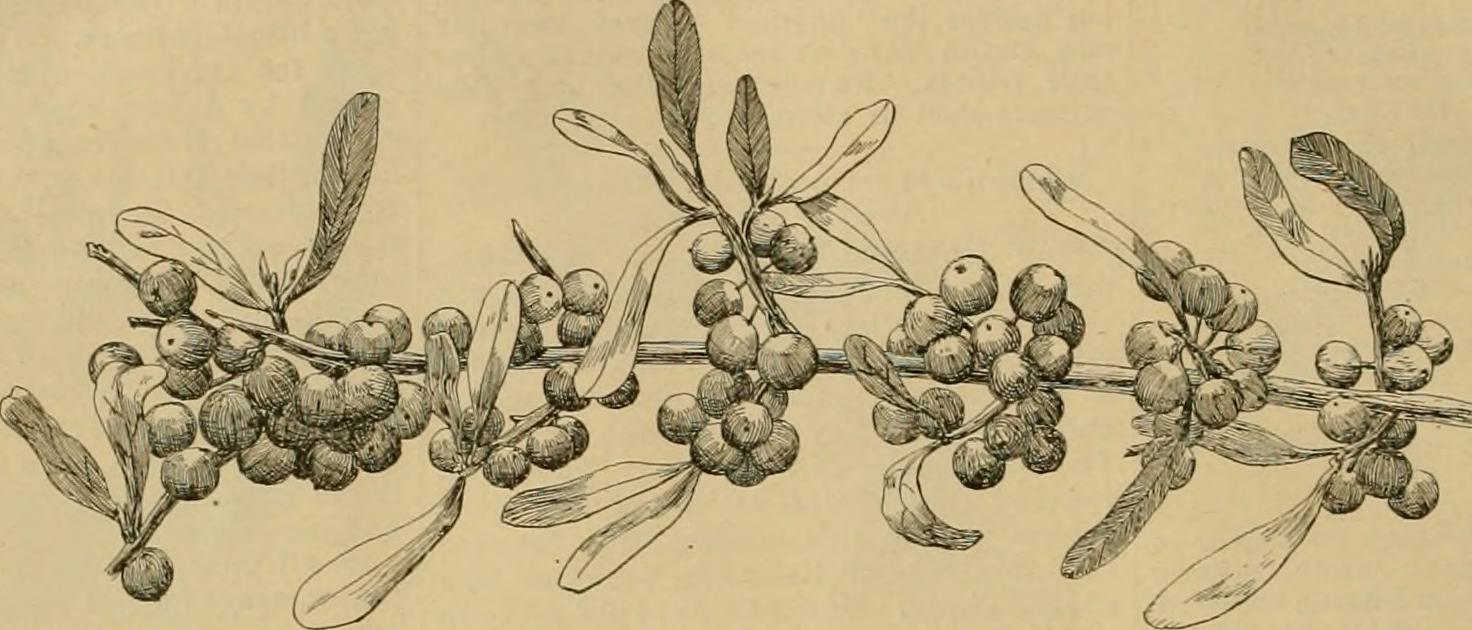

And those 30,000 catalogs at the Royal Botanical Gardens? There’s poetry in them, too. “I can see them as a mix of chapbooks, book art, with a healthy dose of late-night local-channel half-hour-long product commercials,” she says. She finds stories and lives in those books, like ME Blacklock, a “nursery owner and plant breeder during a time when women didn’t often get to do that work.” Isabella Preston, the Queen of Horticulture in the 1920s, who bred lilies, lilacs, and roses.

I asked Erin if caring for, and curating, this collection might intersect with poetry. She sees “both poetry and archival work as potentially radical and political acts. Both of them are relying on words and language to create opportunities of recognition, change, and justice.” Poetry and archiving are “done often as solitary work but are really reliant on the person who is receiving and interpreting the work…Similarly, the internal logic in both poetry and archives is always present within the creator but the logic is not always evident at first glance. Both reader or researcher might need to dive deep to tease out the meaning the poem or archives holds.”

Poems and archives, she says, are “both historical records. They both can be about providing access. Of course, they both require care and observation.”

I like that. Let’s think about poems as objects that deserve care, observation, and preservation. An inspiring way to commemorate the work of others—and maybe the right spirit to help us create poems that can last.

Image Credit: Flickr/Internet Archive Book Images.