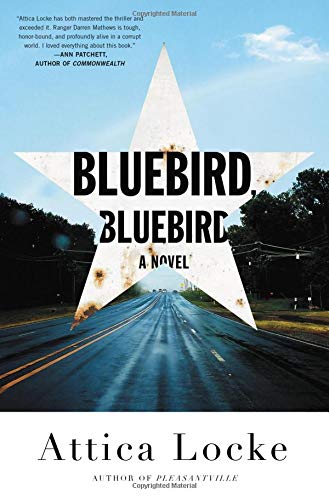

Attica Locke is the award-winning author of Pleasantville, winner of the 2016 Harper Lee Prize for Legal Fiction, Black Water Rising, and The Cutting Season, and worked as a writer and producer on Fox’s Empire. She is also a native of Texas, and descends from two long lines of Texans. It’s that history of the black community in rural Texas that she set out to write about in her new novel, Bluebird, Bluebird, about Texas Ranger Darren Mathews. She spoke to The Millions about race, crime, and all the “weird shit” you see on Highway 59.

The Millions: I saw you speak about this book at BookExpo this year, and you said you want to write a book that expressed the complexity of the black experience in Texas—that black Texans face prejudice, but also love being there and think of it as their home. Your previous books have also been set in Texas, but is this book different as far as what you’re trying to convey about that experience?

The Millions: I saw you speak about this book at BookExpo this year, and you said you want to write a book that expressed the complexity of the black experience in Texas—that black Texans face prejudice, but also love being there and think of it as their home. Your previous books have also been set in Texas, but is this book different as far as what you’re trying to convey about that experience?

Attica Locke: It’s one thing to talk about urban black folks in Houston living a relatively cosmopolitan life. But it has always been true of black folks anywhere in the South—the towns and the rural areas are infinitely more lawless and terrifying than Atlanta or Dallas or Houston. It’s when you get out into the rural areas with a small town sheriff and their version of law enforcement. In the black psyche it’s like, that’s where shit can go wrong. You get pulled over somewhere in the middle of Podunk wherever and nobody ever hears from you again. I do think that writing about the rural area makes this book series different. I also think it speaks to the idea of people who set down agrarian roots, and that was very much my family. My family never left Texas during the great migration. Part of that is class; we owned land, and the sense that you would give that up to move to an apartment building in Chicago was crazy. We hear so much about stand your ground in the lens of the Trayvon Martin tragedy, but the flip side of stand your ground is black folks saying you know what, we built this, we’re not going anywhere. We built this place, we are a huge part of it, and the worst of this state do not get to define the entire state. And I meant for Texas to be a stand-in for the country. I do not believe white nationalists in Charlottesville get to define what America is. They are a very loud and very visible symptom of a big-ass problem, but they’re not the whole of what we are.

TM: Randie, the widow of the murdered black man, voices that attitude that you mentioned when she says, why did he come to rural Texas? Of course something horrible was going to happen. And Darren tells her that that’s exactly why he stays. He says being a Texas ranger is a calling, and calls the Jasper murder his 9/11—the moment he decided to stand up and say no, this is our land too, and you can’t make us leave. When I read that I thought, this sounds like what Attica said. Was there a similar moment for you, where you said okay I want to tell this story, we need to speak against this?

AL: I will say that there’s a supreme irony that I wrote this book before Donald Trump was elected. After the election I thought, oh my god, my book just changed. I didn’t change a single word, it was already written, but suddenly there was a kind of urgency behind it that I had not necessarily intended. What changed is that now all of a sudden you don’t have to dig down to find these stories, people are walking in the middle of the street wearing their white nationalist pride. I don’t know that there was a specific incident that led me to it. It’s just a lot of things coalesced at once. I’ve thought for a while about why my family never left Texas, and that made me think about what it means to stay and fight.

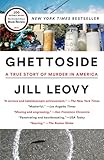

I remember when I realized I wanted to write about a ranger. I knew I wanted the series to go up and down highway 59 and it was my agent who said I think you need a main character to take you through this. And when I thought about the types of characters that could move with that kind of freedom, a Texas Ranger came up. I’d always said my whole career I’d never write about a cop, and then here I was thinking about writing about a cop and remembering having read Ghettoside by Jill Leovy and having read that the flip side of our current conversation about the over-policing of black life is a conversation we need to have about the under-policing of black life. There’s a statistic that in all kinds of crimes, when the victim is black, that is where the prosecutorial system falls apart. That’s when people serve less time. It doesn’t matter if a white person or black person did it—when people of color are victims of crimes, they are least likely to get justice. So that’s the flipside of over-policing, and that was kind of an epiphany, to take a law enforcement officer—a black law enforcement officer—and ask these larger philosophical questions of what are we as black folks to do? When is it safe for us to follow the rules?

I remember when I realized I wanted to write about a ranger. I knew I wanted the series to go up and down highway 59 and it was my agent who said I think you need a main character to take you through this. And when I thought about the types of characters that could move with that kind of freedom, a Texas Ranger came up. I’d always said my whole career I’d never write about a cop, and then here I was thinking about writing about a cop and remembering having read Ghettoside by Jill Leovy and having read that the flip side of our current conversation about the over-policing of black life is a conversation we need to have about the under-policing of black life. There’s a statistic that in all kinds of crimes, when the victim is black, that is where the prosecutorial system falls apart. That’s when people serve less time. It doesn’t matter if a white person or black person did it—when people of color are victims of crimes, they are least likely to get justice. So that’s the flipside of over-policing, and that was kind of an epiphany, to take a law enforcement officer—a black law enforcement officer—and ask these larger philosophical questions of what are we as black folks to do? When is it safe for us to follow the rules?

TM: In the past few years the policing of black lives has become a predominant conversation, at what point during those events were you writing the book, and did that affect it at all? It’s like the book becomes an explainer without meaning to be.

AL: This book is so pointedly contemporary. In all of my books it really matters to me that from page one the readers know where they are in space and time. The first book was 1981, The Cutting Season took place three or four years before it was published. This book seems like so right now, there was a sense of having to stay really clear about what you want to say and not letting the news change how a chapter plays out. Where I’ve gotten nervous—I think I put it in the voice of his uncles when they talk about the different approaches to protecting black life. One uncle, who was a ranger himself, believes that the badge in the right hands could be the thing that saves black lives, and protect it. And his identical twin brother, who was a criminal defense attorney, said the law is a thing that black people need protection from. In my writing I said both of these men were holding on to their own creed that held black life as holy and worthy of continuance. It is the most naked statement that I’ve ever made about the fact that black lives matter. It is no surprise that I believe that black lives matter, that I am about that movement. It’s no surprise that I have a problem with “all lives matter.” But it is something to put that down on paper. It was something when I wrote one little bit where Darren nakedly says “I’m here for Michael.” Missy, the other [white] victim, I can get 20 people here for her in about an hour. I can get Dateline here for her. I can get 20/20. But this man needs my help. That’s a bold to write and sometimes uncomfortable.

TM: A lot of characters in the book are loosely based on your family. The roadside café is similar to one your great-grandmother ran, the locations are close to where your family lived, and you have twin great uncles. Was writing about an area that is so closely tied to your family, and writing in some ways about your family, at all constricting?

AL: No, not at all. I think I felt that more with my first book Black Water Rising because Jay Porter is very clearly a sketch of my father. I think the way in which I’m borrowing my family’s history here is more generalized—the idea of setting down roots, the idea of black women who catered to black travelers on the highway who had nowhere else to go. It isn’t so much that Geneva in the book has the same personality as my great grandmother, it’s just I just grew up with all of this stuff as cultural wallpaper, and so I was just pulling from the familiar. But I didn’t necessarily feel that I owed a representation of my family.

TM: Did you know your great grandmother?

AL: Oh, yes. She passed when I was maybe 10 or 11, so I spent a lot of time with her. The café was gone, it was just stories and old pictures.

TM: I was looking at photos of Corrigan, Texas, on Google Maps when I learned that that’s where your great grandmother’s café was, and I assumed it was a town similar to Lark in the book. Just looking through those photos I was like, oh yeah, this is where the book takes place. I almost wish I had looked through those before I read the book.

AL: I’m glad you did that, because the other thing about this book is that it is a window of Texas that is not the classic southwestern big sky country. East Texas is nothing like that. It is nearer to Louisiana—I call it Louisiana’s fraternal twin. They are connected in some way. It’s lush and filled with forests of pine trees, lots of bayous and creeks, it’s not like the arid southwest. Even my editor, when I started sending pictures to give her an idea for the cover, said, oh you know I’ve never been to east Texas and now I get it. The idea that people would be introduced to the very particular bluesy culture of east Texas is amazing to me.

TM: The Aryan Brotherhood of Texas (ABT) play a big role in the book. When I read it, I thought, she could not have known that her book was going to come out a month after an enormous white supremacist rally. The portrait of the ABT, especially Keith (Missy’s widower, a man connected to the ABT), ends up being at least empathetic, if not sympathetic, but there are a few moments where you understand Keith and the pain that he was in. How did you approach writing about a group, and even in a few chapters writing from the perspective of Keith, when they have views that are antithetical to your life and characters’ lives and your family’s life going back generations?

AL: A couple of things. One—as a writer I believe that villains and villainy have to be complex. I also think it’s important that in Charlottesville what you saw was a bunch of young guys in polo shirts—you need to understand that that is what it looks like. I think writing from that point of view for a chapter is to say this is actually still a human being. He’s not a monster. He’s actually still a fucking human being. I think that for me I’m always interested in getting at the psychological wounds around racism–be they the wounds of the victims of racism, or be they the psychological wounds of the perpetrators of racism–because I firmly believe the unconscious is at play in all of this. Without giving too much away about the ending, I think there is a realization that it’s people’s confused feelings about the other that create this thing that we are mistaking for hate, but that deep down should be called something different. It could be called envy, it could be called love, it could be called fear. I’m always looking to somehow find out what’s going on at the level of the psyche. Yes there are sociopaths or people who are off the rails crazy. But people come in clean, out of the womb, and there are life experiences that begin to shape your thinking about things. I don’t know that human beings’ first fundamental impulse is hate. It doesn’t mean that you don’t circle around and get there, but what I’m interested in is how the fuck did you get there? And maybe in that investigation there’s a way to get to the core of this sickness that has been a part of our nation for so long. For me it’s just deeper than straight hate. I think that at the level of the subconscious there’s a realization for some white folks that you didn’t really do anything by yourself. There’s almost an infantile way that you participated in the birth of the country. You weren’t out there doing the real shit. You could not have survived a new land, swampy conditions in the south, land that you were trying to tame, you could not have done that by yourself. The level of dependence that you had on black bodies makes people’s heads explode. I think people can’t tolerate the fact that that is how we’re connected so deeply, the realization that what you present to the world as a superior race that ran everything is not really true. You could not have done it without black labor, without black bodies, in so many ways. I think that level of dependence, and that unconscious knowledge that you’re not as great at all this as you thought you were makes you black out.

TM: Again, without giving too much away, the book explores how what initially appears to be a strictly segregated town is infinitely more complicated than that.

AL: I think that for some of the current racists that we’re seeing out and about in the world, racism came from the question, how come I’m falling behind? A lot of it is your own inadequacy. If you tell a certain group of people that there’s such a thing as white privilege, and they don’t seem to benefitting from it at all, and then here’s Barack Obama who went to Harvard, it can make you feel inadequate, and then it morphs into a feeling of hate or the other, but it’s really some shit going on within you.

TM: Even though the series will be about Darren, there are three incredible female characters in this book that are so different, and each of them is a version of a familiar black female character. Geneva is a wise matriarch, Bell was an uneducated teen mother who now depends on her adult son for support, and Randie is a beautiful jet-setter in a cashmere coat. But each of these women push back against that character type. Was that intentional?

AL: I did mean that for Geneva. I wanted for her to convey—don’t be fooled by this tableau of black maternal warmth and I’m cooking this, I’m baking that. She keeps Darren at arm’s length until he earns her respect. I meant that on purpose, definitely.

Bell, I don’t know where she came from, I literally have no idea. I knew his mother didn’t raise him, and I knew I wanted there to be a class element to it, but it wasn’t until I wrote a scene where she was chipping nail polish off of her toe with a beer, that’s when I knew her instantly. And then I just kind of went with it.

TM: The richest guy in Lark owns a house that’s a scale model of Monticello, and his dog lives in a scale model of the White House. Is that based on anything?

AL: The only thing that it’s based on is that you see weird shit like this up and down highway 59. You see all kinds of crazy, I don’t understand what the culture of it is except showing off. I have pictures of people who have a huge pistol in their yard—when I say huge pistol I mean they built an iron 32-foot pistol that just sits in the front yard. You just see all kinds of crazy stuff. It just came from the quirkiness of some of these small towns.