In the climactic scene of Close Encounters of the Third Kind—soon to be re-released on its 40th anniversary—a massive UFO lands at the base of Devils Tower in Wyoming. Scientists watch in awe as long-missing pilots from the infamous Flight 19 exit the mothership. A grey-haired, goateed man in a blue suit walks forward between the rapt congregation. He lifts a hand to his face, as if to pause on his chin, but then puts a pipe in his mouth.

That scientist was Dr. J. Allen Hynek, the man responsible for the film’s namesake classification system. Hynek’s cinematic cameo only lasted six seconds, but his spirit infects the entire film. A new biography reveals how Hynek’s life and legend exemplify a lost era. UFO sightings still make the news, but Hynek was something different: a public intellectual who told us to watch the skies.

That scientist was Dr. J. Allen Hynek, the man responsible for the film’s namesake classification system. Hynek’s cinematic cameo only lasted six seconds, but his spirit infects the entire film. A new biography reveals how Hynek’s life and legend exemplify a lost era. UFO sightings still make the news, but Hynek was something different: a public intellectual who told us to watch the skies.

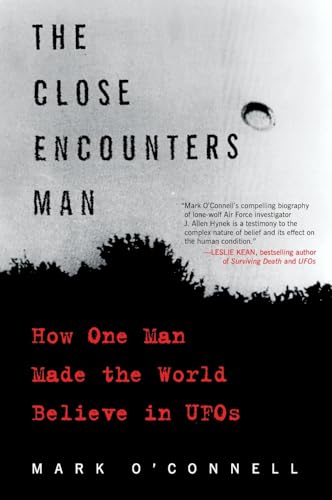

Steven Spielberg explained he “was very influenced by Hynek because he was not looking at UFOs as science fiction, but looking at them as science speculation.” In The Close Encounters Man, Mark O’Connell notes that Spielberg’s friend suggested the title to the director after reading Hynek’s book The UFO Experience. Upon learning of the film’s production, Hynek wrote a curt letter to Spielberg, quipping “Although I am pleased that this recognition is being given to my terminology, I would really have liked to have been informed of this rather than read about it in a national magazine!”

Spielberg apologized, made his creative team read Hynek’s book, and even hired the Northwestern University astronomer as a technical adviser. He could not have made a better choice. Hynek truly embodied the “contradictory nature of scientific inquiry and investigation in the twentieth century, with its simultaneous dependence on and rejection of imagination and wonder.”

Hynek had earned his doctorate in astrophysics at the University of Chicago’s Yerkes Observatory, and began teaching at Ohio State University in 1936. His first government work was during World War II, when he was the reports editor for development of the top-secret proximity fuze at Johns Hopkins. His contributions were brief, but as McConnell demonstrates, cultural history is often the result of unlikely coincidence.

Several years later, when an Air National Guard pilot named Capt. Thomas Mantell tragically died while chasing a “metallic” object “of tremendous size,” the Army Air Force tried to claim that he’d crashed his P-51 “while mistakenly pursuing Venus.” The Air Material Command’s newly formed flying saucer unit, Project Sign, needed a scientist to validate their prosaic conclusion, but “where in Central Ohio could the air force find a professional astronomer who already held a high security clearance and could go right to work with a minimum of red tape?”

Hynek accepted the position, and saw Project Sign as a “golden opportunity to demonstrate to the public how the scientific method works, how the application of the impersonal and unbiased logic of the scientific method could be used to show that flying saucers were figments of the imagination.” For the most part, Hynek toed the party line and pleased his bosses, casting away sightings with mundane explanations. He was responsible for “astronomical assessments” of select cases, and played no part in the infamous “Estimate of the Situation,” a 1948 internal Project Sign report that concluded UFOs were of extraterrestrial origin. The report was rejected by top brass, and led to a less open-minded military take on UFOs. Project Sign was replaced with the appropriately named Project Grudge: “Articles placed in popular magazines portrayed flying saucer sighting reports as pranks, mistakes, and delusions, and reassured the public that there was nothing to fear.”

Meanwhile, Hynek was back in the classroom, and “used his UFO work as a teaching tool of sorts.” In 1952, after a flurry of sightings that included radar-tracked objects over Washington D.C., UFOs became news again. Civilian research groups were being formed across the country. The CIA formed the Robertson Panel, a short-lived investigation that concluded UFOs did not pose a national security threat but, as McConnell writes, “public interest in UFOs—and the public’s growing tendency to report UFO sightings—was of grave concern.”

Project Blue Book, the Air Force’s official investigation into UFOs, was then formed largely as a public relations front, a misdirection. The Air Force didn’t have to work too hard; these were the years of the Contactee movement—people who claimed they had been invited on spaceships and given secret knowledge about the galaxy. Pulpy UFO books and “alien invasion movies had taken the country by storm.” Time and Life magazines were speculating about other worlds. UFOs were silly entertainment.

Hynek “chafed at the miserable circumstance of having to serve a disagreeable master in order to gain access” to the Project Blue Book files. He had to be a public skeptic—see his logic-twisting designation of a Michigan sighting as “swamp gas”—but in private, his views were evolving. After thousands of sightings yielded a fair number of authentically “unknown” cases, Hynek was convinced of two things: UFOs were misunderstood by the scientific community and the public, and they were worthy of serious research.

The government had other ideas. The 1968 Condon Report concluded that the Air Force “should terminate Project Blue Book and get out of the UFO business for good.” Hynek was disappointed, but as part of the system, knew such a conclusion was inevitable. In the years that followed, Hynek continued researching on his own, leading to the classification system that so inspired Spielberg.

Hynek is a deserving subject, but O’Connell’s book also is notable as a methodical history of the UFO phenomena in America—a story so often overshadowed by the Roswell incident. (It is worth mentioning that Roswell was not even on Spielberg’s radar; even though the incident occurred in the summer of 1947, researchers showed little interest in the alleged crash until 1978). McConnell’s a great storyteller, and that’s what needed in a history of American ufology: someone to connect the dots into a narrative.

McConnell reveals how, even in the days of H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds and Percival Lowell’s speculations about intelligent life on Mars, there has always been a symbiotic relationship between science fiction and science fact in the world of UFOs. What Close Encounters of the Third Kind and events like Roswell offer are narratives, stories to help tether the often disparate, mysterious world of UFOs to lived reality. Spielberg’s film doesn’t quite feel dated, but does feel like it came from a more optimistic time. In one of the first scenes, young Barry Guiler awakens in the middle of the night. His toys are spinning and marching, animated by some mysterious force. He goes downstairs. Punctured Coca Cola cans drip on eggs, lettuce and meat strewn across the kitchen floor. In Spielberg’s vision, UFOs and their occupants are more mischievous than nefarious. Like us, they are curious.

McConnell reveals how, even in the days of H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds and Percival Lowell’s speculations about intelligent life on Mars, there has always been a symbiotic relationship between science fiction and science fact in the world of UFOs. What Close Encounters of the Third Kind and events like Roswell offer are narratives, stories to help tether the often disparate, mysterious world of UFOs to lived reality. Spielberg’s film doesn’t quite feel dated, but does feel like it came from a more optimistic time. In one of the first scenes, young Barry Guiler awakens in the middle of the night. His toys are spinning and marching, animated by some mysterious force. He goes downstairs. Punctured Coca Cola cans drip on eggs, lettuce and meat strewn across the kitchen floor. In Spielberg’s vision, UFOs and their occupants are more mischievous than nefarious. Like us, they are curious.

During the Condon study, Hynek traveled to Colorado with his colleague Jacques Vallée, the esteemed French astronomer and ufologist. They were talking about what got them interested in science, and Hynek’s confession was telling: “So many people get into science looking for power, or for a chance to make some big discovery that will put their name into history books…For me the challenge was to find out the very limitations of science, the places where it broke down, the phenomena it didn’t explain.” Like a great scientist should be, Hynek was in awe of the world—of all things seen, and unseen.