You only need to wade a few steps into Henry David Thoreau’s Walden before tripping over these words: “It is hard to have a southern overseer; it is worse to have a northern one; but worst of all when you are the slave-driver of yourself.” For an author like Thoreau, an active and outspoken abolitionist, the insensitive aphorism seems like a profound contradiction of his character. In A Fugitive in Walden Woods, author Norman Lock imagines an appropriate response to such a statement, delivered by the novel’s narrator, Samuel: “It is much, much worse, Henry, to be driven by a vicious brute whom law and custom have given charge over one’s life than by an inner demon.”

Lock’s premise is clever: In the summer of 1845, just as Thoreau embarks on his experiment in simplicity on Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Walden property, the Virginia slave Samuel Long cuts off his own hand, slips his manacle and — as the law of the day held — steals himself away from his master. He is conducted north via the Underground Railroad to Concord, Massachusetts, where Emerson sets him up in a second cabin in Walden Woods and tasks him with keeping tabs on the hermit-philosopher down the way. During the year he spends in Concord, Samuel finds himself amid a community of famous intellectuals and abolitionists — Emerson, Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and William Lloyd Garrison. The community is sympathetic to Samuel’s struggle, but the contrast between their extreme privilege and Samuel’s hardship often strains their attempts at genuine human connection.

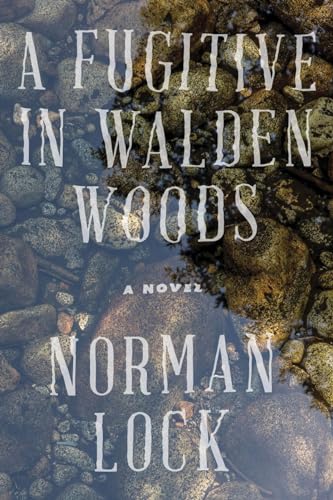

The novel comes as the next installment in Lock’s series of American Novels, each of which engages with seminal nineteenth-century American authors and ideas. In each volume the first-person narrator functions as a kind refractive lens, bending and blending together a generation of texts and ideas within a single mind, and yielding a spectrum of impressions on the development of American culture and identity. But the book does more than parrot various ideological positions. A Fugitive in Walden Woods bursts with intellectual energy, with moral urgency, and with human feeling. Lock’s characters are not reducible to their ideas, but rather animated and complicated by them. In this way the novel achieves the alchemy of good fiction through which philosophy takes on all the flaws and ennoblements of real, embodied life.

As fascinating as it can be to watch the philosophical debates unfold, it’s often an even greater pleasure to witness Samuel yawn while these giants of the American canon pontificate at each other. Their talk is often compared to the buzzing of insects, and once to “a play without an interlude.” Emerson idealizes the soul, Thoreau nature, Hawthorne bemoans sin, but Samuel finds none of these compelling. For Samuel, abstract musing on Nature or Reality is a luxury that can distract from the actual substance (and struggle) of nature and reality. Over and over, the text returns to this question: What function do philosophy and literature serve in the material world, where people suffer constantly and nature endures indifferently?

Though Samuel’s critiques of these writers are many, the novel is far from a transcendentalist takedown. In fact, the narrator calls his work a “eulogy” for Thoreau, who died early from tuberculosis. His tribute is not a counter-Walden but a necessary companion piece, meant to both honor and challenge an old friend. Henry’s frank wisdom and his earnest, observant care for the gifts of the wild world are not missed, but rather contextualized within a restless man attempting to craft from ideas a physical life, a brilliant aphorist whose rhetorical fervor sometimes leads him into self-contradiction.

Samuel, too, is full of contradiction. He does not yet know “how to be,” especially in relation to these men. Part of him values their support and respect; he knows their attitudes are not mere performances. Later in his life, it will be these men who settle Samuel’s absurd self-theft debt with his former master, and thereby legally free him. But, still in Walden Woods, Samuel is beholden to the protection and esteem of well-meaning white men; his fugitive status permits no illusion of independence. What is he to make of self-reliance? He often feels reduced to “the object of other people’s goodness,” his story nothing but a powerful “tool” for the abolitionist cause. So another part of him wants resistance, revolt, it wants broken glass and righteous blood, and wants it now; he can’t suffer the thought of writers carrying out life — theirs, his — on scraps of paper, essays or stories or laws. That he should thank these men is preposterous. “I insist,” he writes, “that I am in debt to no one for restoring what ought to have been mine since birth…What is this impertinence but the self-reliance that Emerson espouses and Thoreau practiced in his lifetime. Like them, I wish to be reliant on no one but myself.”

The novel draws a sharp distinction between Henry’s and Samuel’s search for self-reliance in Walden Woods — a vast difference in privilege, trauma, and future prospects divides them. However, amid their disparate experiences, Samuel recognizes in Thoreau a kindred question: How am I to be, for myself and for others? In order to stand by the broad democratic implications of an experiment like Walden — the self-reliance and self-sufficiency of each individual — mustn’t he eventually compromise his own aloof simplicity and enter into the complications of human community for the sake of those whose individual rights are denied? “His self-reliance was partly self-delusion, as it must be for any mortal,” Samuel writes of Henry. This is true not only because Thoreau himself received ample support from his community (he was, after all, living on Emerson’s land), but also because the practice of pure self-reliance is a contradiction in a society that privileges only some with freedom. Ultimately, when Thoreau’s character truly does right in the novel’s dramatic final moments, it’s not by anything he writes or says, but by his willingness to “violate his principles” to help preserve Samuel’s freedom.

A reader would be right to be wary of Lock’s narrator — the author is a white man inventing and taking on the voice of a former slave. I hesitate to pass any definitive judgment on this kind of narrative presumption (a word which Lock himself uses to describe his relationship to the narrator), fraught as it is with a whole history of appropriation and exploitation. A reader may, in fact, be justified in rejecting Lock’s narrator and his premise out-of-hand. For my part, I can only affirm fiction as a space where both writer and reader seek honest communion with the lives of others, and say that, as I see it, Lock’s portrayal of Samuel seems as empathetic and complex as one must expect from a writer who knowingly attempts to cross such a gulf of experience.

Throughout the book Lock pays frequent homage to true accounts of slavery and escape by writers like Frederick Douglass, Henry Bibb, Solomon Northup, and Moses Roper, lifting up these accounts rather than trying to overwrite them with his own invention. The novel makes no attempt to compete with such narratives. Instead, it works to interrogate an intellectual tradition that was developing during the same period in a privileged Northern enclave by placing in conversation with those writers a person whose experience is drastically different from their own, and who could pose a worthy challenge to some of their deeply held notions of Nature and God and Soul and self-reliance.

There are occasional moments when the narrator’s voice falters, when the author leans away from the specificity of Samuel’s experience toward the dubious suggestion of some archetypal Slave Narrative in which, as Samuel claims at one point, “the particulars might be different, but the sorrows were the same.” Doubtless, there is much Samuel rightly identifies with in the stories of other former slaves, but in equating one’s experience to the others, the author plays into precisely the erasure of individual identity from which his character is attempting to recover. Samuel’s life, his memory, and his pain are his own, and the narrative is strongest when Lock pays mind to these particulars.

The narrative leap is clearly not one Lock takes lightly, nor does he try to make himself disappear beneath Samuel’s guise. In subtle metafictional moments, the novel foregrounds these issues of empathy and appropriation, consistently calling the reader’s attention back to Lock’s role as author. An epigraph by Thoreau, from Walden, opens the subject: “I should not talk so much about myself if there were anybody else I knew as well.” There’s an implicit irony to such a quote, given that it precedes a piece of profoundly other-focused fiction — and indeed, the novel critiques the idea by demonstrating how literary navel-gazing can gloss over the suffering of others. Several times later on in the novel, Samuel himself claims to speak for the men in his story, and gives his own defense for the presumption:

None can know another’s mind. Nonetheless, we do speak and write of others as if we have known them well. What can Melville have known of Ahab, or Edgar Poe of Usher, or Hawthorne of Dimmesdale? And yet they have written of them in the belief that we possess a common soul. So it is that I have found within me courage to speak of and for various persons met during my stay in Walden Woods as though I had sounded to the bottom of them.

Thoreau’s aphorism is right, of course: there is nobody we know so well as ourselves. But as Samuel indicates, Thoreau is wrong too: we may never truly know each other, but without the willingness to take those first steps of imagination and empathy toward the lives of others, Walden is nothing but a place to hide.