How do two writers live and write together?

The answer changes through time. In her introduction to The Diaries of Sofia Tolstoy, Cathy Porter describes how Sofia laboriously copied Leo Tolstoy’s work: “After the baby had been put to bed, she would sit at her desk until the small hours, copying out his day’s writing in her fine hand, telepathically deciphering the scribble.” When reading Sofia’s diaries, kept from age 16 until she died in 1919, it’s hard not to feel her creative frustration. “To each his fate,” she writes. “Mine was to be the auxiliary to my husband.”

The answer changes through time. In her introduction to The Diaries of Sofia Tolstoy, Cathy Porter describes how Sofia laboriously copied Leo Tolstoy’s work: “After the baby had been put to bed, she would sit at her desk until the small hours, copying out his day’s writing in her fine hand, telepathically deciphering the scribble.” When reading Sofia’s diaries, kept from age 16 until she died in 1919, it’s hard not to feel her creative frustration. “To each his fate,” she writes. “Mine was to be the auxiliary to my husband.”

Historian Alexis Coe writes that being married helps academics get ahead, but only if they are male. In the Lenny Letter, she expands on her findings from reading the acknowledgements in books, “male historians often call wives research assistants while female historians say husbands were patient/encouraging.” Her article is a fascinating look at a selected history of literary couplings, from the F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald to Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne.

Bruce Holsinger, a novelist and academic, also searched acknowledgments and found many examples of male authors thanking their wives for typing manuscripts. People continue to share examples on Twitter using the hashtag #ThanksForTyping. A click shows there are many women of the past century who might find Sophia Tolstoy’s words familiar.

While a word processor changes dynamics, the way a work is attributed often reflects a power relationship between two authors. When a couple are both authors, the relationship is often colored by the politics of their day.

In 2017, many couples are striving for a more equal balance of power in relationships. There are as many ways this can play out as there are couples, but I want to continue the conversation. How does a modern couple balance the domestic with a literary life?

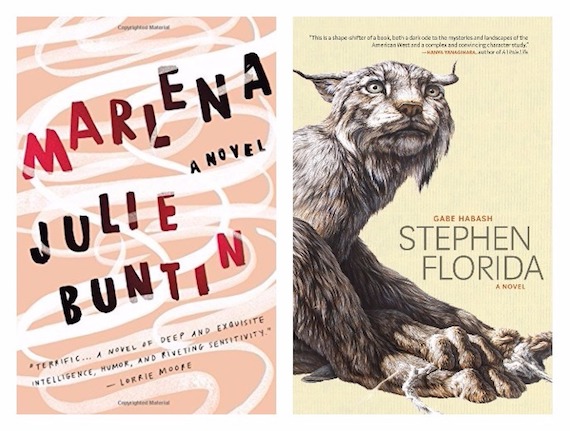

Julie Buntin’s Marlena is one of the most energetic and vibrant debut novels released this spring, which Kirkus calls, “as unforgettable as it is gorgeous.” Her partner, Gabe Habash, just published one of the breakthrough debuts of the summer, Stephen Florida. NPR calls it, “starkly beautiful and moving.”

I was intrigued to learn that Buntin and Habash are partners and live together. While I assume they both do their own typing, I wonder how this particular modern couple make it work. By email, I asked them about reading each other’s work, egos, money, and solitude.

The Millions: Gabe, did you know Julie was a writer when you first met?

Gabe Habash: Yes, we met in grad school. We had a craft class together, and I was immediately struck (and probably a bit intimidated) by how smart and perceptive she is. But we didn’t actually have any workshops together so I didn’t read her writing until after I graduated. By then she was starting what would eventually become Marlena. I’m grateful I get to watch how she shapes her work. It’s amazing.

TM: Julie, you knew Gabe was a writer when you met. Did you consider this a good or bad thing?

Julie Buntin: Soon after we started dating I realized that we weren’t going to have a problem with competitiveness when it came to writing—I’d dated a writer before, and that had been an insidiously toxic problem, but Gabe and I never had that issue. Mostly because of him, I think—Gabe is immune to comparing himself to other people. It’s very strange and I envy it. I am not immune, but am trying to get better.

TM: Is Gabe the first reader of your work?

JB: He is. It’s a bit of a crutch. When I was deep in revisions of Marlena, after he’d already read it a couple times, I would sometimes send altered drafts to my editor without showing Gabe, but for the most part, he sees everything before it goes out. I’ve delayed submitting things to the point of missing deadlines because I want Gabe’s take first.

TM: Is Julie the first reader of your work?

GH: Yes, she’s always been my first reader. I wrote the first 50 pages of the novel and showed them to her to find out if it was bad. I wouldn’t write any more until I knew she liked it because I respect her opinion more than anyone else in the world—if she says it’s bad, it’s bad. Julie is just as good of a reader as a writer, if that’s possible. There are numerous reasons the book is dedicated to her.

TM: Has she or he ever said anything about your writing that you wished she hadn’t?

GH: Nope.

JB: Gabe’s going to be embarrassed that I’m sharing this, but I showed him the first few pages of a new novel a while back. He said: “You can do better.” In general, I appreciate that we’re at a place where we don’t need to dance around anything, but that work was a little raw for a fully honest assessment—still, I’m glad he told me what he really thought.

TM: Do you believe Gabe when he praises your work?

JB: I do. Gabe is a bad liar, and I think my answer to the previous question gets at the directness of how we talk about writing.

TM: Do you ever feel threatened by the success of Julie’s novel?

GH: Honestly, no. Our books are so different and I love Marlena, so it never felt like they were competing against each other. Also, just watching someone work at something so hard, putting years into it and going through really challenging moments with it because it’s a vital part of her life—it’s impossible for me to feel jealousy or to feel threatened when I saw that because I knew how much telling the story meant to Julie.

TM: Marlena was blurbed by Lorrie Moore, is an Indie Next Pick, and was selected by The Rumpus Book Club. For a debut novel, it doesn’t get much better. Did you ever worry that Gabe’s book might not be as well received?

JB: I have never doubted for a second that Stephen Florida would be well received. Even when a number of major publishers passed, I had no anxiety about it eventually finding the right home—Gabe did, but I didn’t. I don’t think it’s blind wife faith either—I hadn’t had that same certainty when his previous novel was on submission. After reading Stephen Florida I felt a flicker of jealousy—he wrote a book that alchemizes his talent and experience and deep thinking about literature into a novel that’s exhilarating to read. If anything, I feel a little smug about all the good reviews it’s getting. Like—told you, world!

If anything (please forgive how pretentious this sounds), I worried that his book might be taken more seriously from a critical perspective, because Marlena is about girls and Stephen Florida is about boys. That doesn’t seem to have been the case, at least not so far, but I did wonder if that was going to be an issue. I’m still not sure how I would have handled that.

TM: Writing and books aside, what do you both love to do?

GH: We like to take walks like old people. We watch Game of Thrones and Twin Peaks. Some day, I swear, I will get her to like video games. We both like horror movies, which Julie will point out to you is some study’s number one metric for determining relationship compatibility.

TM: You both work in publishing and are writers. Is it ever too much?

JB: It can be. Sometimes we get home and we’re eating dinner and we go from talking about our books to talking about books that he’s reading or assigning for review to talking about books on submission at Catapult or something I’m editing or a writer I want to get to teach and we have a moment where one or the other of us snaps and is like, no more books. Please, enough. And so we try to introduce spaces into our lives for other stuff. It can be overwhelming. Sometimes it feels like we’re always sort of working. But most of the time it’s nice to never have to translate why doing this work matters so much to me.

TM: What about money?

GH: As writers who also work in publishing, we are obviously very rich.

Julie, I think, needs writing on a daily basis. I go through long periods in which I barely think about it, and then write all at one time. So having no day job I think is more for Julie—she would use the time, whereas if I weren’t in the middle of a project I would just wander around like a vagrant, wondering how to fill the hours.

JB: Oh, this is a hard one. I would be lying if I said I never thought about this. It has occurred to me that in some ways I’ve made my writing life harder because I’m married to another writer, instead of someone with more financially-driven ambitions. Gabe is better at balancing his work life and writing life—he’s more of a daily chipper, less of a binger—and as much as I love my job, I feel like I am giving something up every minute that I am not writing. But maybe I would go crazy if I had that time. Or maybe I’d have finished another book by now! Who knows—like most writers, I’ve always had a job or two or three and squeezed writing in somehow.

All this said, I’ve learned a lot about writing from Gabe, from his edits on my work, from the process of editing his. There a lot of writer couples. Maybe once you become accustomed to the benefits of having an in-house reader and editor, not to mention someone who challenges you to think more deeply about how and why you write, I don’t know, those things become more important than a pension. We’ll see if I feel the same way in 20 years.

TM: What is the best part about living with another writer?

JB: Never having to explain why you don’t want to go out.

TM: What is the worst?

GH: Whatever plans you might have, they can get eliminated at any time if one of us is in the writing fugue. You just have to accept that your plans are canceled in that instance.

TM: Do you understand Gabe’s work better than anyone else?

JB: I don’t know that I understand it better than anyone else, but I do think I understand how it came to be better than anyone else. I look at the first page and I can see ghosts of cut phrases, all the thinking that went into making the book what it is—it’s a privilege.

TM: Do you understand Julie’s work better than anyone else?

GB: I have no idea! You’ll have to ask her. Julie understands my work better than anyone else.

TM: What is your favorite thing that the other has ever written?

GH: The last chapter of Marlena is two and a half pages. I think about it all the time. It’s contains everything that came before but also opens the narrative up; I love how it shows the story is longer than the book itself.

JB: I love that first page. It starts, “My mother had two placentas and I was living off both of them…” and ends like this: “I believe in wrestling, and I believe in the United States of America. I am a motherfucking astronaut.”