I’ve become transfixed by the golem. This figure from Jewish folklore — a man made from clay and brought to life by a mystic — raises central Jewish questions: How can human beings participate in the creative power assigned to the divine? What are the limits of human endeavor? What role do power and rage play in the history of a marginalized people? Whose body gets to be seen as human and whose as a soulless monster?

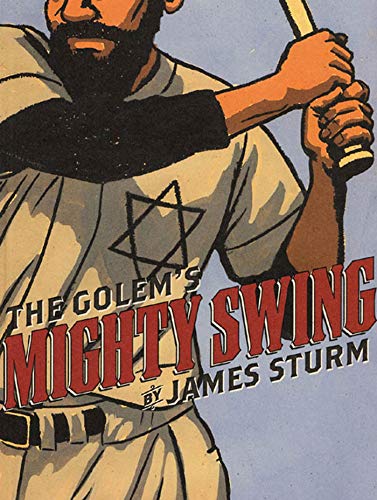

In his 2001 graphic novel The Golem’s Mighty Swing, out in a new edition from Drawn and Quarterly, James Sturm brings a golem to life to animate questions about the meaning of Jewishness in America — and the meaning of America.

The Golem’s Mighty Swing follows the Stars of David, a barnstorming, Depression-era Jewish baseball team, as they travel through rural America. To make ends meet, they accentuate the spectacle of their otherness, playing into the figure of the nomadic “wandering Jew.” When car troubles put them in sudden need of a big payday, the Stars of David accept an offer from Victor Paige, a sleazy baseball promoter, to outfit one of their players in the golem costume from the hit film The Golem: How He Came Into the World. The poster for their next match proclaims: “The Jewish Medieval Monster! See Him With Your Own Eyes!” The story the team tells about themselves becomes a story about the monstrosity of their irreducible otherness.

As the team settles into the next town, tensions mount. An editorial in the local paper declares, “The excitement of Saturday’s game should not disguise a simple fact: The Golem is not Putnam’s most dangerous adversary. There is a greater threat that the Putnam All-Americans must vanquish, the threat posed by the Jews.” The game eventually erupts into a violent riot. The uncontrollable rage often associated with the golem emerges, though here the golem is not its source.

The Golem’s Mighty Swing poses central questions about what America has been, what it is, and what it might become. Sturm spoke with me over email about the novel and the broken America into which it has been rereleased.

The Millions: The questions that The Golem’s Mighty Swing asks about racism and xenophobia are perennial American questions, but they seem newly relevant today. Do you see the book differently as it reemerges into today’s political climate? Has it been strange to revisit your work during the rise of Trump?

James Sturm: I do see the book differently. In writing it, it felt more personal; I was trying to work through my own issues of identity and relationship to being a Jew to America. Rereading the book in preparation for the new edition, what struck me is how this story is basically an anatomy of a race riot that strongly evokes current events: a race-baiting, crass salesman manipulating the media for profit. The character of Victor Paige wasn’t a character I took that seriously in writing the book — now that character is president.

TM: In his introduction to the new edition, cartoonist Gene Luen Yang writes, “James shows us what America wishes it had been, and what America actually was. By rubbing the rose tint from our memories, he uncovers our nation’s truest self.” Was this your intent? How do you think the novel engages with the interplay of those two Americas — the one it wishes to have been (and perhaps aspires to be) and the one it truly has been?

JS: Most of the book’s Jewish characters are immigrants or first-generation Americans — they fled from pogroms, hostile empires, and emerging nations. They desperately wanted to believe in the ideals of America. For the team’s black player, Henry Bell, his view of America is far different — his family came to America in chains. A baseball story set in the 1920s is especially susceptible to evoking that rose-tinted strain of American nostalgia. I did want the book to challenge this view. I keep coming back to the present political moment and this creepy notion of “making America great again.” Talk about rose-tinted glasses! Who was it great for? And if so, on whose backs was that “greatness” generated?

TM: In that introduction, Yang mentions a lecture in which you called comics the intersection of poetry and graphic design. Could you say more about that? How do you find that narrative emerges out of that intersection?

JS: I think of comics as images you read, not just illustrations. With every panel I am trying to communicate something specific. Or several things and in this case there is thought given to information hierarchy. This to me is graphic design. And when I think of poetry, I think of conflating language and then artfully positioning text on a page, which is what a cartoonist does when filling caption boxes and word balloons.

TM: The golem is a figure from Jewish folklore that has captured imaginations far beyond the communities in which it originated. I love how The Golem’s Mighty Swing activates various moments in the history of the golem, from its origins in Jewish mysticism to its popular depiction in the 1920 film The Golem: How He Came Into the World. What initially drew you to the golem? What do you find compelling about it? Did the story you wanted to tell come out of the golem, or did the golem present itself as a way to tell the story?

TM: The golem is a figure from Jewish folklore that has captured imaginations far beyond the communities in which it originated. I love how The Golem’s Mighty Swing activates various moments in the history of the golem, from its origins in Jewish mysticism to its popular depiction in the 1920 film The Golem: How He Came Into the World. What initially drew you to the golem? What do you find compelling about it? Did the story you wanted to tell come out of the golem, or did the golem present itself as a way to tell the story?

JS: Marvel comics initially introduced me the golem legend (The Invaders #13, to be specific). Though now it is obvious that the Marvel universe is a very Jewish universe, that was not apparent to me at age 12, and seeing the Golem and knowing it came from my religious tradition made me take note. I think most artists and writers relate to the golem legend as we attempt to mold something in our image (or collective image) and try to imbue it with life.

TM: In his book The Price of Whiteness: Jews, Race, and American Identity, historian Eric L. Goldstein writes about “how Jews negotiated their place in a complex racial world where Jewishness, whiteness, and blackness have all made significant claims on them.” The Golem’s Mighty Swing carefully thinks through Jewishness in the American context as it relates to whiteness and blackness: the Stars of David play for segregated audiences, and the player who ultimately takes on the role of the golem is black and not Jewish. When writing the novel, how were you thinking about navigating this complex history of American Jewishness and racialization?

TM: In his book The Price of Whiteness: Jews, Race, and American Identity, historian Eric L. Goldstein writes about “how Jews negotiated their place in a complex racial world where Jewishness, whiteness, and blackness have all made significant claims on them.” The Golem’s Mighty Swing carefully thinks through Jewishness in the American context as it relates to whiteness and blackness: the Stars of David play for segregated audiences, and the player who ultimately takes on the role of the golem is black and not Jewish. When writing the novel, how were you thinking about navigating this complex history of American Jewishness and racialization?

JS: In the first half of the book, the Stars of David were presented as Americans first and foremost. Their position in society is precarious, but they are never seriously threatened. In the second half of the book, they are seen as Jews first and foremost, and being seen through that lens leads to the violence. I was also trying to call attention (and to counter) prevalent stereotypes with the mention of Joe Hush, the chatty Native American.

TM: In The Golem’s Mighty Swing, the Jewish baseball players occupy a space between assimilation and otherness. The narrator — manager and third baseman Noah Strauss — says, “My father would be gravely disappointed knowing we are playing on the Sabbath…His imagination lives in the old country. Mine lives in America and baseball is America.” Yet the success of the team depends on playing up their exoticized Jewishness: they’re advertised as “the bearded wandering wonders,” Strauss goes by “The Zion Lion,” and ultimately the golem embodies the perceived monstrosity of their otherness. What do you hope the novel says or asks about diasporic Jewish experiences?

JS: When you become an American, what does it then mean to be Jewish (or Irish or German or Chinese)? What part of one’s identity has to be sacrificed to be part of the “melting pot?” And who ultimately decides whether you are an American or not? There are cycles of history where Jews can wear their heritage proudly on their sleeves and other times they will be beaten and murdered for doing so. As good as America has been to Jews, we know that can change quickly.

There’s also a mention in the book of black ball players dressing up as Zulus that isn’t all that much different from what the Stars of David do. What is one’s “authentic” identity? This was a question I took seriously in writing the book.

TM: Two pivotal scenes in the novel center on baseball games, which are the site where a lot of the novel’s underlying psychological drama occurs. As someone who isn’t much of a sports person, I was particularly impressed by the way you brought those scenes to life on the page — they’re incredibly absorbing. How did you think about how to represent the drama, motion, and suspense of those games in the medium of comics?

JS: I learned most about depicting baseball in comics from Japanese Manga. Though I couldn’t read the Japanese, I could follow the action very clearly. The storytelling through the artwork was so clear and precise. I could tell when a batter was expecting a fastball and got a curveball. There would be pages of a pitcher trying to pick a runner off of first base. Each character had a very specific body type and body language. Japanese baseball manga was light-years ahead of any American baseball comics.

TM: What are you reading, thinking about, and working on these days? What’s next for you artistically?

JS: I recently read Amos Elon’s The Pity of It All: A Portrait of the German-Jewish Epoch, 1743-1933 and a recently translated Korean graphic novel, Uncomfortably Happily by Yeon-Sik Hong. I also just read Eleanor Davis’s comic book, Libby’s Dad. All of these books were excellent. And after 30 years, I reread Hermann Hesse’s Narcissus and Goldmund.

JS: I recently read Amos Elon’s The Pity of It All: A Portrait of the German-Jewish Epoch, 1743-1933 and a recently translated Korean graphic novel, Uncomfortably Happily by Yeon-Sik Hong. I also just read Eleanor Davis’s comic book, Libby’s Dad. All of these books were excellent. And after 30 years, I reread Hermann Hesse’s Narcissus and Goldmund.

I’m currently working on my next graphic novel, Off Season. It’s contemporary fiction about a father of two young kids recently separated from his wife against the background of this past election season. Excerpts of the book were published in Slate.

It is hard not to keep thinking about politics these days.