“That eye with which any artist looks at life is really dumb in a lot of ways. Usually, students forget how people make a living, for instance. Well, that’s just my job — to remind them that’s what literature is about, really, how people live. The blood of family and the living of money.”

—Grace Paley

Grace Paley’s death, in 2007, was a unique loss. Poet, polemicist, and unsurpassed short story master — from her debut collection, The Little Disturbances of Man’ to Enormous Changes at the Last Minute and Later the Same Day, she cast an unforgettably wise, sharp eye on human foibles, personal and political.

Grace Paley’s death, in 2007, was a unique loss. Poet, polemicist, and unsurpassed short story master — from her debut collection, The Little Disturbances of Man’ to Enormous Changes at the Last Minute and Later the Same Day, she cast an unforgettably wise, sharp eye on human foibles, personal and political.

In the process, she paved a path for others to follow, even if no one could match her unique blend of urban wit, street smarts, and tensile sentences.

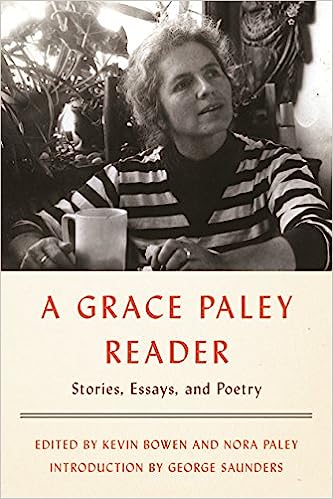

A new collection, A Grace Paley Reader: Stories, Essays, and Poetry,’ (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), edited by the poet and painter Kevin Bowen and Nora Paley, Grace’s daughter, brings together work from the course of her career and provides a much-needed reminder of its importance.

There is much talk these days of “Resistance Literature’’ — a way of hearkening back to the protest prose of the past in response to the current serio-comic catastrophe. Unfortunately, much of it is cant — Facebook posts disguised as literary rebellion, angry outbursts where cool, committed heads are needed.

But Paley was the real deal.

Let’s start with the essays reprinted here, from her collection, Just As I Thought, since the power of the stories speaks for itself, radiantly.

Let’s start with the essays reprinted here, from her collection, Just As I Thought, since the power of the stories speaks for itself, radiantly.

“The Illegal Days’’ deals, matter-of-factly, with the author’ decision to have an abortion back in the ‘40s, when it was dangerous and illegal (a period, sadly, that we seem about to revisit).

“My abortion was a very clean and decent affair, but I didn’t know until I got there that it would be all right,’’ she writes.

The doctor’s office was in Manhattan, on West End Avenue…The nurse was there during the procedure. He didn’t give me an anesthetic. He said, ‘If you want it, I’ll give it to you, but it will be more safer and better if I don’t.’ It hurt, but it wasn’t that painful. So I don’t have anything traumatic to say about it. I was angry that I had to become a surreptitious person, and I was in danger, but the guy was very clean, and he was very good, and he was arrested within the next year. He went to jail.

She goes on: “I didn’t feel bad about the abortion. I didn’t have the feelings that people are always describing. I may have hidden some of those feelings, but having had a child at that time would have been so much worse for me.’’

Being Grace, she doesn’t sugarcoat things, either.

But I’ll be very truthful. I never liked the slogan, ‘Abortion on demand, and most of my friends hated it…It’s such a trivialization of the experience. It’s like ‘Toothpaste on demand.’ If somebody said there should be birth control on demand, I would say yes. That would make a lot of sense. If I ask for a diaphragm, if I ask for a condom, I should just get it right off the bat.

But an abortion…After all, it’s a surgical procedure and really a very serious thing to undertake. It’s not a small matter.

Similarly, in the midst of a full-throated denunciation of the first Gulf War, now seen, ironically, as a “good’’ conflict in the light of its disastrous sequel, she stops a woman passing out pamphlets at a Cooper Union peace rally to ask a question: “’How come you guys left out the fact that Iraq did go into Kuwait? How come?’” She said, ‘That’s not really important.’ ‘I know what you mean,’ I said, ‘but it happens to be true.'”

What is true, as opposed to what people believe, or want to believe, about themselves and the world they live in, is Paley’s sweet spot, the reason that she made a mark from her earliest days, when she was encouraged at a New School class taught by W.H. Auden, incongruously enough, to “write in her own voice,’’ as a chronology included in this volume recounts.

Her work remains indelible.

“You know, I like your paragraphs better than your sentences,’’ an insensitive lover remarks, with casual cruelty, in “Listening,” a story from Later The Same Day included in an earlier volume of her Collected Stories.

“You know, I like your paragraphs better than your sentences,’’ an insensitive lover remarks, with casual cruelty, in “Listening,” a story from Later The Same Day included in an earlier volume of her Collected Stories.

“My husband gave me a broom one Christmas,’’ she notes dryly, in “An Interest In Life,’’ from Little Disturbances. “This wasn’t right. No one can tell me it was meant kindly.”

“The Loudest Voice’’ describes a young girl’s insistence, over her mother’s objections, in singing in a Christmas pageant at school. After seeing the day through, she reflects: “I was happy. I fell asleep at once. I had prayed for everybody. My talking family, cousins far away, passerbys, and all the lonesome Christians. I expected to be heard. My voice was certainly the loudest.”

In his eloquent and loving introduction to this volume, George Saunders makes the case for Paley as a “secular saint,” an honor I think this Bronx girl may have flinched from. He also describes her, ingeniously, as a “thrilling postmodernist,” in the Barthelmesque tradition; it’s endearing, but not convincing, and comes across as a justification of his own fictional method.

Nora Paley’s “Afterword’’ is more pointed, and accurate:

As her child I absorbed the global way my mother took in the day. She experienced time as a bathtub calibrated by stories however they were sensed. As a young kid I recognized her open water intelligence but there was always a shark swimming through it.