The focus of Millions staffer Claire Cameron’s forthcoming novel is the poignant journey of a dwindling family of Neanderthals, diminished by hardship, nature, social taboos, and finally, Darwinian reality. The Last Neanderthal shines a mirror into our own humanity by featuring a family in peril, whose communication through rudimentary vocabulary is nevertheless sufficient to express the full range of human emotion. Meeting basic survival needs is more than a full-time job for these Neanderthals — not so different, then, from the vast majority of families in today’s world.

Against this spare background, an ambitious young scientist feverishly toils to untangle the story of Neanderthal remains recently discovered in a French cave. She works against the ticking clock of her advancing pregnancy and the shifting power dynamics in her professional field. The time period in which she lives may be infinitely more complex than that of the Neanderthals, yet we are clearly meant to find parallels between her challenges and the subjects of her research.

Why and how did Cameron land on this topic? What are we to take away from The Last Neanderthal? The author’s insights into how she mined this subject will enhance the reading experience of this unusual book.

The Millions: The Last Neanderthal is a book with a very unusual premise — the end of the Neanderthals. How did you come up with it?

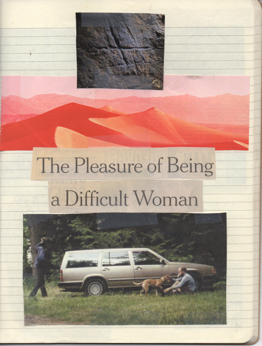

CC: I have life-long obsessions, like many people do, but I didn’t realize the consistency of my obsessions until I started keeping notebooks. The ideas in my notebooks are often visual; there is a lot of cutting and pasting involved. A page doesn’t make any sense and I often can’t articulate why I’m collecting certain things.

Pictured is an example of a page where I combined marks possibly made by Neanderthals in Gorham’s Cave in Gibraltar with desert sand, feminism, and a domestic looking Will Oldham with a dog and a Volvo. All the big themes of my novel are there, though I didn’t know it at the time.

Pictured is an example of a page where I combined marks possibly made by Neanderthals in Gorham’s Cave in Gibraltar with desert sand, feminism, and a domestic looking Will Oldham with a dog and a Volvo. All the big themes of my novel are there, though I didn’t know it at the time.

Evidence of Neanderthals in my notebooks traces way back, but my notes got more pointed in 2010 when a team of scientists found out that many modern humans carry genes from Neanderthals. People of European and Asian descent have between 1 percent to 4 percent Neanderthal DNA. This is a sign of interbreeding between modern humans and Neanderthals, something that had only been in the realm of speculation before then (though to be fair, the people who write Neanderthal porn on the Internet already knew). That was the premise that intrigued me, how did the two groups make contact?

TM: How did you research/learn about the Neanderthals?

CC: A recent wave of research has helped to revise the scientific view of Neanderthals. Much of it, including the Neanderthal genome, shows they were more like us than we previously imagined. I wanted to write characters inspired by this research. I did a lot of study on my own, but the most important step I took was to work with John Shea, an archaeologist and paleoanthropologist at Stony Brook University in New York.

When I first talked to Dr. Shea, he told me about reading an older Neanderthal novel. As a scientist, the story frustrated him so much that he tossed the book over his shoulder, scoring an accidental perfect hit into the wastebasket. We agreed that he would look for wastebasket moments in my work.

There were many wastebasket moments but his notes gave me a framework. I started to think of the science like a creative constraint. When I read convincing research, I used it as a rule that I had to work within.

TM: Although highly emotional, the Neanderthals’ story is told within a limited vocabulary, starting with their names — ‘Girl,’ ‘Him,’ etc. — presumably reflective of their brain capacity. Is this how you think of it, and can you tell us about how this kind of simplicity affected your writing process?

CC: When David Mitchell talked about writing in the future or past, he said he looks for what a character might take for granted. I want to see through the eyes of the main character. I develop a set of beliefs for her and, as part of that, imagine what she takes for granted. That is how I get immersed to the point where the story dominates my work—the character becomes big enough to crowd out the writer.

One of the things I decided is that my Neanderthals didn’t believe in talking all the time. They lived in a small family group and had intimate knowledge of each other. Every thought didn’t need to be said out loud. In fact, if they could hear me now, they might think I was a crowthroat — the crow being the worst offender when it comes to constant, mindless squawking. Also, I speculated that this was part of their culture because talking took more effort in the physical sense, they had to force out each word. So the cost of each word was considered carefully before it was spoken.

Once I shut up in my mind — or taking more silence for granted — I could hear all the thoughts I have that I don’t articulate. If you want to move a chair to a different part of the room, as one example, you do a silent calculation. It would be difficult to put into words what you are thinking. And if you practice keeping your trap shut, your senses wake up. You start to notice new things, like a bird that often calls when I step outside. I imagine she is an early warning system to let the other critters know, maybe, “Hey everybody, the squawking long pig is on the move!” So, I don’t see the Neanderthal language as a reflection of a simpler thought process, but as a sign of a different kind of strength.

TM: There is a leopard that seems to have a similar level of cognition to the Neanderthals in the book. Can you talk about that?

CC: My story is told through the eyes of a Neanderthal. We see the world much as she does. One of the things she believes is that there is little distinction between herself and the land around her. There is a glossary of Neanderthal words at the beginning of the book. One of the words, deadwood, expresses this idea.

Deadwood: A body on the other side of the dirt; used as an equivalent to our idea of death, though it expressed a change of state rather than a permanent end.

I developed the glossary as way to get inside the head of this particular Neanderthal, another attempt to uncover what she took for granted. If she saw herself on a continuum with other animals, rather than distinct or special in some way, it followed that she didn’t see much of a physical difference between her body and the land. She might also blur her mental identity. If she is interested in hunting or tracking, she assumes that another animal thinks in much the same way.

TM: Nature plays a critical role in your fiction. Your last novel, The Bear, opens with a tragedy at a campsite — two parents killed by a bear — and their two young children left to fend for themselves in the wilderness. We are outdoors for most of The Last Neanderthal as well. How do you think of the role of nature affects your storytelling?

TM: Nature plays a critical role in your fiction. Your last novel, The Bear, opens with a tragedy at a campsite — two parents killed by a bear — and their two young children left to fend for themselves in the wilderness. We are outdoors for most of The Last Neanderthal as well. How do you think of the role of nature affects your storytelling?

CC: I often write about the place I am not. I lived in London, U.K., for about eight years and one day I got out of the tube at Oxford Circus. It was busy and as I tried to exit, I got stuck in a human traffic jam. There were too many people squished into an underground corridor. It became a gridlock of hot bodies pressed against each other. My inner Canadian quietly panicked, but this was London. Everyone remained calm and reserved. A message passed along the corridor until enough people backed out at one end and there was room to move again. Shortly after I started to write my first novel, The Line Painter. It was about Canada and specifically the vast, empty-of-people north of Ontario. I wrote out of a longing to be there, like it might be the antidote to being stuck in a human traffic jam.

If I write from that place, of longing, then the place I am writing about becomes like an obsession. I feel intense homesickness and idealize it in the same way. The place is mine and I can imagine it as an intense version of itself. That also means that I use the setting to serve the story and forget any urge to create a faithful portrait.

Right now I live in an urban neighborhood in downtown Toronto. I miss the access to Europe that I used to have from my London base. I miss the mountains. Though I get outside as much as I can, the life that I used to live, the one where I spent months in the wilderness, now resides most predominantly in my imagination. That’s why I write about it.

TM: In each of these novels, you are making keen observations about parents, even if they are absent. Can you comment on that?

CC: I love what Alexander Chee said, “you write to describe something you learn from your life but that is not described by describing your life.” My father died when I was young. I struggled with grief for many years. First I was locked in and couldn’t talk about it and after a while I got angry. I went through all the steps, but as I did, I held fast to the idea that I would eventually get over it. That’s how we talk about grief, that it is something to overcome.

I was surprised to find that when I had kids, I went through a stage of grief again. This time I grieved for my dad. I understood what it must have been like to know you are dying and to leave small children behind.

Grief doesn’t go away, it’s something you live with. And hopefully it becomes something that makes you stronger. I suppose that’s why it keeps coming up in my work, because I’m trying to figure it out.

TM: The stark vocabulary of the Neanderthals is especially marked in contrast to the parts of the novel that takes place in the present when we are in the company of archeologist Rosamund Gale, or Rose. What role does Rose play in the narrative, including her impending motherhood and her professional struggles?

CC: In 1921, H.G. Wells wrote a short story about Neanderthals called, “The Grisly Folk.” He described them this way, “a repulsive strangeness in his appearance…his beetle brows, his ape neck, and his inferior stature.” This was very much the thinking of his day, that a Neanderthal was like the archetype for an ogre. Since then our view of them has evolved, but we’ve really used them as a foil to ask questions about ourselves: What makes humans special? Asking questions in a self-centered way hasn’t given us much insight into them.

I wanted to focus on Neanderthals. In some ways, Rose is a foil for the main Neanderthal character, Girl. While Rose’s experience are important, she is also a way to gain insight into what a Neanderthal might have been like. Girl is the star of the show.

TM: Given today’s sense of — or lack of sense of — community, is there a message embedded in the relationships between and among members of “the Family” of last Neanderthals, and similarly, among the characters who live in the present time?

CC: I think of a novel as a question that takes the length of a book to ask. I was not searching for a message so much as thinking through the implications of how our modern family structure works.

I got interested in this question when my neighbor, a private, quiet person, told me about growing up in Newfoundland without central heat. He slept piled in a bed with his brothers, the youngest a bed wetter. My neighbor remembers getting up in the morning with a wet leg. When he stood, his pajamas would freeze and crackle. As he is so private I assumed this must have driven him mad, but when I asked he looked at me like I was crazy. Without his brother’s body heat to keep him warm, it was his body that would have frozen.

So I started thinking about that, what if we thought about family like that — the people who literally keep you alive? Grocery stores, electric lights, and central heat change how we think of our physical needs. Do they also change how we think about families? And what do we need to survive, both physically and mentally, in modern life?

TM: Rose is a scientist who seems to have an instinct to “go it alone,” even though she is close to nine months pregnant. In that sense, she relates to her subject of study — Girl. How did your sense of female independence inform your development of these characters?

CC: Rose gets pregnant and assumes this is a fairly natural and ordinary thing to do. As baby starts to grow, the timeline for her project gets crunched. Her pregnancy gives her a sense of impending doom. When she becomes a mother she will be sidelined, whether by herself or by others, so she needs to get shit done.

There is a group of women scientists on Twitter, many with an interest in archeology, who are posting photos with the hashtag #pregnantinthefield. I love the photos because seeing the possibilities helps us all believe them. Polly Clark, author of Larchfield, wrote eloquently about this, “I wasn’t a reluctant mother at all. But I had no notion of being simply a vessel: I stubbornly continued to think that, as an individual, I still mattered.” The women in these photos matter.

There is a group of women scientists on Twitter, many with an interest in archeology, who are posting photos with the hashtag #pregnantinthefield. I love the photos because seeing the possibilities helps us all believe them. Polly Clark, author of Larchfield, wrote eloquently about this, “I wasn’t a reluctant mother at all. But I had no notion of being simply a vessel: I stubbornly continued to think that, as an individual, I still mattered.” The women in these photos matter.

But the other day I said a quiet apology to Rose for giving her a sense of urgency about her work — I know she is the kind of female character that might be criticized. I had to write about her though, specifically how her professional interests and personal ambition sits at odds with parenthood. This was my experience. This is the experience of so many parents.

TM: What can we learn from the Neanderthals in thinking about our own humanity?

CC: We can fall into the trap of thinking that the way we do things now is normal, but it’s important to look back for context. As the always quotable Winston Churchill said, “The longer you can look back, the farther you can look forward.” We are Homo Sapiens, a self-obsessed people who like to tell stories. I’m really writing about modern humans, aren’t I? A novel becomes a way of looking at history to think through our inheritance.

TM: Do you have a new novel in process, and if so, can you tell us about it?

CC: My obsessions sometimes turn into novels and sometimes they don’t. Or sometimes they combine to become something I didn’t expect.

At the moment, I’m trying to understand the advances in physics, specifically how ideas about quantum gravity have completely changed our understanding of reality. I’m also comparing translations of Beowulf, what does the Irish poet Seamus Heaney do with an Old English poem, versus J.R.R. Tolkien’s handling of a similar passage? I can only hope that these two interests don’t combine.