When writers marry other writers, the union can prove to be painfully inequitable. One career often soars above the other, sometimes in a permanent fashion, with the spouse dwelling seemingly in the shadows. Nick Laird, despite his achievements as a prize-winning poet, is probably primarily recognizable to the public as the husband of Zadie Smith. Likewise, Raymond Carver’s widow, Tess Gallagher, is an accomplished but unheralded poet herself. Not since Mary and Percy Bysshe Shelley, one could argue, has there been a writer-couple of parallel impact, a husband and wife duo making contributions of equal standing to literary history.

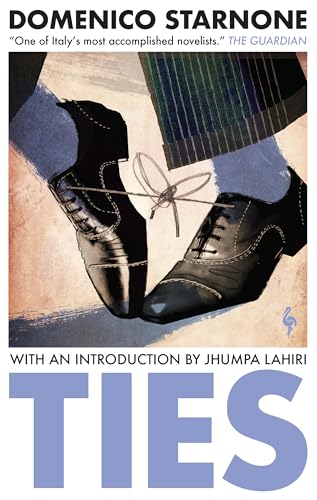

It was revealed last year that global phenomenon Elena Ferrante was married to another writer, Domenico Starnone, a name known primarily in Italian literary circles. Ferrante, of course, has achieved deserved renown in America and worldwide for her astounding Neapolitan tetralogy. As of now, Starnone, winner of one of Europe’s most prestigious literary awards, the Premio Strega, remains read and lauded mainly in his native Italy and parts of Europe. Yet if his brilliant new novel Ties (Europa Editions; translation by Jhumpa Lahiri) — only his second to be translated into English — is any indication, Starnone’s international reputation abroad may be due for a bump of its own.

Starnone’s engrossing and masterful story of the Minori family, told from a trifecta of perspectives — the betrayed wife’s letters in the opening section, the doddering husband’s viewpoint in the middle, the closing section recounted by the downtrodden adult daughter — is almost too impeccable a work. Shaped and polished as meticulously as an Etruscan urn, no portion, no narrative ligament, no single word feels out of place. Starnone wastes no time gathering narrative steam but, almost before the first word is sounded, pitches the reader directly into the chaotic epicenter of a damaged couple’s erotic drama and then, in a way only geniuses can do, guides the tale grippingly toward a conclusion that has that rare combination of qualities: stupendous unpredictability alongside perfect inevitability. “All great art is inevitable,” goes the (probably apocryphal, but no less true) Leonard Bernstein aphorism. One lays down Starnone’s novel in the end almost exhausted at what the form can still do to us.

The basic story itself is familiar. A man, Aldo Minori, betrays his wife, Vanda, and the resulting emotional devastation wrought upon the family, including their children, Anna and Sandro, turns out to be of far greater magnitude and implication than could have been predicted. Aldo’s world, inner and outer, becomes vulnerable to the savages of grief, fury, and revenge. For decades he tries to contain the damage, repress his past, but is thwarted by his own bungling aloofness and flawed memory. Using the simple conceit of infidelity and the protagonist’s futile attempts to transcend the past, Starnone manages to capture a glimpse of a human emotional universe much larger, far grander, and more intimidatingly incomprehensible than one could have imagined. Then as the simple machinery of the Naples-based drama churns, as Aldo Minori’s nose is forced into the filth of his past, a theme emerges that transcends the novel’s overlapping sub-themes of desire, escape, betrayal, family, discontent, chaos, time, and the myth of Pandora’s box — it’s the idea of the nature of the human soul.

What, if anything, does the soul contain? The familiar Delphic maxim “know thyself” comes to mind — but can we really know ourselves, our souls? What is it that can or should be known? Why does Aldo, an ostensibly ordinary or even decent man, behave the way he does, why does anyone? During my reading of Starnone, I happened to come across another piece of wisdom, a fragment by Heraclitus that seemed more to the point. Heraclitus wrote: “You will not find out the boundaries of the soul, even by traveling along every path: so deep a measure does it have.” Here, the soul is not knowable at all, not inwardly containable, but just the opposite, it casts us outward, conceiving of the spirit as an infinite shadow-complex in which the person travels upon endless roads, drifting in a permanent state of displacement. Heraclitus’s forte was the metaphysics of inconstancy — chaos, change, transformation, contradiction, the ceaseless disorder of the human spirit — and it’s the idea of chaos itself, the eruption of dissonances between action and reaction, around which Starnone’s novel coheres.

In the visual center of the novel, as Aldo Minori picks through documents containing his life’s work that had been scattered around the apartment after a mysterious act of vandalism in his home, the writer says of himself:

Was I that stuff?…A concrete accumulation, through decades, of papers, hand-written, printed, a trail of scrawls, reports, pages, newspapers, floppy discs, USB fobs, hard disks, the cloud? My potential realized, Myself made real: that is to say, a chaos that could overflow, if I just typed Aldo Minori, from the living room to the Google archives?

The examination of his own writing seems to show that all that work the aging artist did throughout his life was, itself, a regime of containment, a futile attempt to make knowable an unpredictable soul, an unwinnable struggle to which, as it happens, no less are his daughter and wife later fated.

As are we, perhaps. What’s instantly noticeable about the book is the extent to which Ties is in conversation with Elena Ferrante’s early novel The Days of Abandonment. Both stories take place in Naples; both books are the same manageable read-in-one-sitting length. In both, a woman and her children are abandoned for no apparent reason by a man of good standing. Only, in Ferrante, we strictly follow Olga, the embittered wife, whereas in Domenico Starnone we cling largely but not only to betrayer Aldo Minori’s viewpoint and then to the perspectives of his wife and daughter. This is entirely appropriate, given that the central ideas in either book are essentially at odds. Ferrante turns us inward, forcing Olga to attempt to “know thyself,” an effort that, after a string of gut-wrenching domestic horrors, delivers her to her own body, her Self, her striving to know what lay within. Starnone does the perfect opposite, forces Aldo outward, revealing the soul’s ongoing volcanic eruption, the eternal outflow of indecipherable Everything, of which he is fated to learn nothing at all.

As are we, perhaps. What’s instantly noticeable about the book is the extent to which Ties is in conversation with Elena Ferrante’s early novel The Days of Abandonment. Both stories take place in Naples; both books are the same manageable read-in-one-sitting length. In both, a woman and her children are abandoned for no apparent reason by a man of good standing. Only, in Ferrante, we strictly follow Olga, the embittered wife, whereas in Domenico Starnone we cling largely but not only to betrayer Aldo Minori’s viewpoint and then to the perspectives of his wife and daughter. This is entirely appropriate, given that the central ideas in either book are essentially at odds. Ferrante turns us inward, forcing Olga to attempt to “know thyself,” an effort that, after a string of gut-wrenching domestic horrors, delivers her to her own body, her Self, her striving to know what lay within. Starnone does the perfect opposite, forces Aldo outward, revealing the soul’s ongoing volcanic eruption, the eternal outflow of indecipherable Everything, of which he is fated to learn nothing at all.

It’s an interesting thought to imagine Ferrante and Starnone in dinnertime back-and-forths over the issue. Elena shouting “Within, within!” while Starnone barks back “Without, without!” The eternal question is never really laid to rest, can never quite leave them be, even after the publication of two brilliant novels on the topic. They are fated — perhaps as all married couples are fated — to engage in an unwinnable battle in which both are right, yet both wrong, and for which a satisfactory conclusion can neither rightly be drawn nor, perhaps, should be.