1.In Havana, Ernest Hemingway’s restless ghost lingers more palpably than in any of the other places in the world that can legitimately claim him: Paris, Madrid, Sun Valley, Key West. Havana was his principal home for more than three decades, and its physical aspect has changed very little since he left it, for the last time, in the spring of 1960.

I’ve been traveling to the city with some regularity since 1999, when I directed one of the first officially sanctioned programs for U.S. students in Cuba since the triumph of Fidel Castro’s 1959 Revolution. As an aspiring novelist, I’ve long been interested in Hemingway’s work, but I had no idea how prominently Havana figured in the author’s life — nor how prominently the author figured in the city’s defining iconography — until I began spending time there.

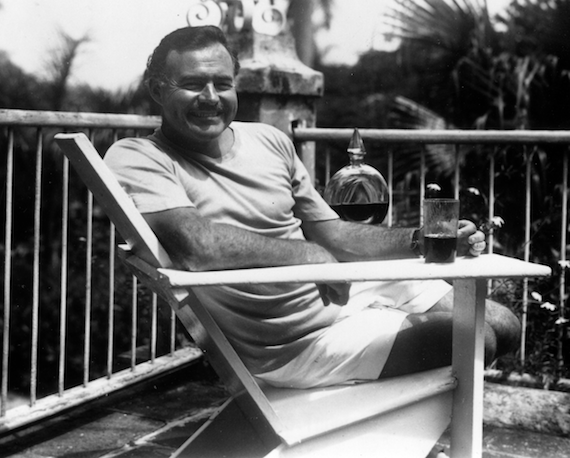

Well-preserved Hemingway locations abound in Havana. They include the Hotel Ambos Mundos, where the author lived throughout the ’30s in a room that is now a small museum; the Floridita, which serves overpriced “Hemingway daiquiris,” and contains a life-size bronze likeness of the writer with its elbow on the bar; the Bodeguita del Medio, which has Hemingway’s signature on the wall and claims to have been his favorite place for a mojito; and La Terraza, the restaurant overlooking the small harbor that was the point of departure and return for Santiago’s epic voyage in The Old Man and the Sea. These sites are not just tourist spots, though they certainly are that. They also serve as shrines and landmarks in the city’s defining mythology. The essence of this mythology is captured in the black-and-white photos taken in the months following the 1959 Revolution, later made into postcards. These feature images of Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, Camilo Cienfuegos — and Ernest Hemingway.

Well-preserved Hemingway locations abound in Havana. They include the Hotel Ambos Mundos, where the author lived throughout the ’30s in a room that is now a small museum; the Floridita, which serves overpriced “Hemingway daiquiris,” and contains a life-size bronze likeness of the writer with its elbow on the bar; the Bodeguita del Medio, which has Hemingway’s signature on the wall and claims to have been his favorite place for a mojito; and La Terraza, the restaurant overlooking the small harbor that was the point of departure and return for Santiago’s epic voyage in The Old Man and the Sea. These sites are not just tourist spots, though they certainly are that. They also serve as shrines and landmarks in the city’s defining mythology. The essence of this mythology is captured in the black-and-white photos taken in the months following the 1959 Revolution, later made into postcards. These feature images of Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, Camilo Cienfuegos — and Ernest Hemingway.

2.

To get a feel for the author’s Cuba years, let us begin with a single one: 1933, in the midst of the Great Depression. By the third week in July of that year, according to Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story, Carlos Baker’s comprehensive 1969 biography of the author, Hemingway had notched his 100th day of fishing in the waters north of Havana. He’d caught more than 50 marlin, including a 750-pounder he’d brought to hand within casting distance of the Morro, the white stone fortress presiding over the entrance to Havana Bay. The yacht he’d rented had been rammed so many times by swordfish that it was starting to leak, so he decided to buy himself a new one, a diesel-powered, 38-foot cruiser from Wheeler Shipyards in Brooklyn. He named it the Pilar, which was also his secret nickname for his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer — whose family money, as it happened, was financing the couple’s highly mobile lifestyle: a revolving calendar of stays in Havana, Madrid, Paris, New York, Key West, and the Serengeti.

Already a literary star on the strength of his first two novels, The Sun Also Rises (1926) and A Farewell to Arms (1929), Hemingway chose Havana as his base that summer because of its proximity to one of the planet’s best places to pursue big game fish. As he later wrote in Holiday magazine, he was drawn to the Gulfstream, that “great, deep blue river, three quarters of a mile to a mile deep and sixty to eighty miles across.” He was especially captivated by the marlin, which, from the flying bridge of the Pilar, looked “more like a huge submarine bird than a fish.”

Already a literary star on the strength of his first two novels, The Sun Also Rises (1926) and A Farewell to Arms (1929), Hemingway chose Havana as his base that summer because of its proximity to one of the planet’s best places to pursue big game fish. As he later wrote in Holiday magazine, he was drawn to the Gulfstream, that “great, deep blue river, three quarters of a mile to a mile deep and sixty to eighty miles across.” He was especially captivated by the marlin, which, from the flying bridge of the Pilar, looked “more like a huge submarine bird than a fish.”

The author had first visited Havana in April of 1928, for a brief stop on his steamer journey back from Europe at the end of those romantic Paris-based years he later portrayed so vividly in The Moveable Feast (1964). It proved to be a significant layover for Hemingway — and for Havana — because he discovered something about the place that made him want to return. The central ambition of Hemingway’s life was, as he wrote in Esquire in 1934, to create novels and stories “truer than if they had really happened,” and he was continually in search of gritty, colorful, and intense experience that would serve as fodder for this quest. Cuba, like Spain, was an ideal setting for this sort of experience, not only because of the excellent fishing, but also because it was a flashpoint for political upheaval. In April 1931, a general uprising in Spain had resulted in the fall of the Bourbon monarchy, marking the beginning of a new Republic, and in August 1933, a popular uprising in Havana overthrew the dictatorship of President Gerardo Machado. Hemingway, who had a lifelong distaste for authoritarian rule, joined in the celebration of both events, but the turmoil that followed in their wake would have enduring impacts on his creative life.

The author had first visited Havana in April of 1928, for a brief stop on his steamer journey back from Europe at the end of those romantic Paris-based years he later portrayed so vividly in The Moveable Feast (1964). It proved to be a significant layover for Hemingway — and for Havana — because he discovered something about the place that made him want to return. The central ambition of Hemingway’s life was, as he wrote in Esquire in 1934, to create novels and stories “truer than if they had really happened,” and he was continually in search of gritty, colorful, and intense experience that would serve as fodder for this quest. Cuba, like Spain, was an ideal setting for this sort of experience, not only because of the excellent fishing, but also because it was a flashpoint for political upheaval. In April 1931, a general uprising in Spain had resulted in the fall of the Bourbon monarchy, marking the beginning of a new Republic, and in August 1933, a popular uprising in Havana overthrew the dictatorship of President Gerardo Machado. Hemingway, who had a lifelong distaste for authoritarian rule, joined in the celebration of both events, but the turmoil that followed in their wake would have enduring impacts on his creative life.

In the ’30s, according to Carlos Baker, Hemingway was feeling increasing career pressure as an author. The New York critics had savaged his most recent books, Death in the Afternoon (1932) and Winner Take Nothing (1933). He’d written enough stories about sport and animal dismemberment, they complained. Why didn’t he move on to something new? He wrote another novel, To Have and Have Not (1937), and it was a decent story — but decent wasn’t enough. A young novelist from California, John Steinbeck, was garnering critical attention and threatening to usurp Hemingway’s rightful place atop the pantheon of American writers. Hemingway needed a book as great as The Sun Also Rises or A Farewell to Arms — as great, more pressingly, as Of Mice and Men (1937) or The Grapes of Wrath (1939). He needed a masterpiece, and he was worried that he’d lost his ability to write one.

In the ’30s, according to Carlos Baker, Hemingway was feeling increasing career pressure as an author. The New York critics had savaged his most recent books, Death in the Afternoon (1932) and Winner Take Nothing (1933). He’d written enough stories about sport and animal dismemberment, they complained. Why didn’t he move on to something new? He wrote another novel, To Have and Have Not (1937), and it was a decent story — but decent wasn’t enough. A young novelist from California, John Steinbeck, was garnering critical attention and threatening to usurp Hemingway’s rightful place atop the pantheon of American writers. Hemingway needed a book as great as The Sun Also Rises or A Farewell to Arms — as great, more pressingly, as Of Mice and Men (1937) or The Grapes of Wrath (1939). He needed a masterpiece, and he was worried that he’d lost his ability to write one.

All these factors contributed to his decision, in 1936, to go cover the Spanish Civil War as a filmmaker and newspaper journalist. He joined a score of other international correspondents based in the Hotel Florida, in Madrid. He fell in love with a tall blonde writer and war correspondent named Martha Gellhorn, and naively allowed himself to become implicated in some unsavory intrigue with a ring of Soviet advisors to the Republican high command. It was an exhilarating time for Hemingway. He took every opportunity to observe the fighting, both at a distance and up close. The ground shook with daily barrages of Fascist artillery, reducing the Gran Vía to rubble, and he felt more alive than he had in years.

Eventually, the tragic war lurched toward its close. By the winter of 1939, with the triumph of Fascism looking inevitable, Hemingway decided it was time to get back to writing. He packed up his copious notes and booked his passage home to Havana, intending to work on a collection of three long stories or novellas. Instead, he was struck by a sudden inspiration for the story that would become his majestic novel of the Spanish Civil War, For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940). As the words began to pile up in his old fifth floor room at the Hotel Ambos Mundos, his excitement grew. He could feel it. This was the masterpiece he’d been hoping for.

Eventually, the tragic war lurched toward its close. By the winter of 1939, with the triumph of Fascism looking inevitable, Hemingway decided it was time to get back to writing. He packed up his copious notes and booked his passage home to Havana, intending to work on a collection of three long stories or novellas. Instead, he was struck by a sudden inspiration for the story that would become his majestic novel of the Spanish Civil War, For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940). As the words began to pile up in his old fifth floor room at the Hotel Ambos Mundos, his excitement grew. He could feel it. This was the masterpiece he’d been hoping for.

In April of that year, he was joined by Martha Gellhorn, who was to become his third wife. Unwilling to live permanently in a hotel room, she located a down-at-the-mouth estate 15 miles from Old Havana called the Finca Vigía. Though the house was in need of work, it was favorably positioned on a hill washed by cool sea breezes, with distant views of the bone-white city and the glittering blue Straits of Florida beyond. In 1940, For Whom the Bell Tolls was published to critical and popular acclaim. His authorial confidence restored, Hemingway resumed the life of a migratory sportsman, with Martha as his companion and the newly renovated Finca Vigía as his long-term base.

Once the accolades died down, however, he sank into another valley of malaise. As he’d long been predicting, hostilities broke out in Europe. The fighting spread rapidly, and as of December 7, 1941, America too became involved. He’d written his masterpiece, sure, but now the entire world was consumed by war. He’d been a first-hand witness in two of the century’s defining military clashes. The idea of sitting this one out was unimaginable. Still, he wasn’t quite ready to abandon Cuba, or the good fishing, or his comfortable life at the Finca Vigía.

He was on good terms with top officials at the U.S. Embassy in Havana. With their approval, he put together a counterintelligence operation to address the infiltration of Cuba by Nazi spies. It was believed that the spies had found accessories among the many Cubans who supported the new Spanish dictator, Francisco Franco. The situation was seen as particularly dangerous because of the “wolf-pack” of German U-boats preying on Allied shipping throughout the Caribbean. Operations began in the summer of 1942, with the Finca as headquarters and a collection of fishermen, bartenders, prostitutes, gunrunners, exiled noblemen, Basque jai-alai players, and long-time drinking buddies forming the personnel of Hemingway’s counterspy ring.

But intelligence proved an unsatisfying pursuit. Yearning once again to experience the dangers of combat, he showed up at the embassy with an audacious proposal. He would staff the Pilar with a well-armed crew and patrol the island’s north coast, posing as a team of scientists gathering data for the American Museum of Natural History. Inevitably, his reasoning went, they would be stopped by a U-Boat, at which point they would wait for the Nazi boarding party to emerge. His machine-gunners would mow down the boarding party, and his retired Basque jai-alai players would lob short-fuse bombs down the sub’s conning tower. All he needed to make it work, he told the ambassador, was good radio equipment, arms and ammunition, and official permission.

Amazingly, the ambassador approved this far-fetched scheme. The Pilar was outfitted with a powerful radio, a set of .50-caliber Browning machine guns, grenades, bombs, and a variety of small arms. Martha suspected that it was all just a ruse to fill the Pilar’s tank with strictly rationed wartime gasoline so Hemingway could resume his fishing trips, and in reality the detachment of faux scientists never did encounter a U-boat. But the author’s experiences during that period gave him some terrific material for fiction. The novel that resulted, Islands in the Stream (1970) — unfinished in his lifetime and only published posthumously — contains portrayals of tropical seascapes that rank among the best passages of nature writing in fiction.

Amazingly, the ambassador approved this far-fetched scheme. The Pilar was outfitted with a powerful radio, a set of .50-caliber Browning machine guns, grenades, bombs, and a variety of small arms. Martha suspected that it was all just a ruse to fill the Pilar’s tank with strictly rationed wartime gasoline so Hemingway could resume his fishing trips, and in reality the detachment of faux scientists never did encounter a U-boat. But the author’s experiences during that period gave him some terrific material for fiction. The novel that resulted, Islands in the Stream (1970) — unfinished in his lifetime and only published posthumously — contains portrayals of tropical seascapes that rank among the best passages of nature writing in fiction.

When Martha left to become a war correspondent in London, Hemingway remained in Havana, his drinking on the rise, and the Finca Vigía in a state of increasing disarray. The truth was, he was torn. A part of him felt strongly that he should be following Martha off to the war, but another part was deeply reluctant to leave the place that he’d come to consider home, his beloved cats, his friends, his record player, the long days out on the Pilar, and the mojitos and daiquiris at his Havana haunts. Still, when Collier’s offered him a job covering the Allied invasion of Europe, he managed to pull himself together. He placed the cats in good homes and shuttered the Finca Vigía for a long absence.

Like many other episodes in his colorful life, Hemingway’s experiences in World War II make for an interesting story, though that story is beyond the scope of this article. Suffice it to say that participating in yet another war seemed to give his spirit a fresh infusion, and he returned from Europe in May of 1945 with his fourth wife, Mary Welsh. Together they resumed the wandering life, alternating seasons in Havana and Sun Valley with frequent trips to Africa, Italy, and Spain. The Finca Vigía now had a staff of seven full-time servants and a well-stocked bar and kitchen. Houseguests included Hollywood luminaries such as Gary Cooper and Ava Gardner, whom he’d gotten to know in Sun Valley and from working on the movie versions of For Whom the Bell Tolls (1943) and To Have and Have Not (1944).

Like many other episodes in his colorful life, Hemingway’s experiences in World War II make for an interesting story, though that story is beyond the scope of this article. Suffice it to say that participating in yet another war seemed to give his spirit a fresh infusion, and he returned from Europe in May of 1945 with his fourth wife, Mary Welsh. Together they resumed the wandering life, alternating seasons in Havana and Sun Valley with frequent trips to Africa, Italy, and Spain. The Finca Vigía now had a staff of seven full-time servants and a well-stocked bar and kitchen. Houseguests included Hollywood luminaries such as Gary Cooper and Ava Gardner, whom he’d gotten to know in Sun Valley and from working on the movie versions of For Whom the Bell Tolls (1943) and To Have and Have Not (1944).

In December of 1950, he finally got around to writing a story he’d long had in mind, about an old fisherman from the Cuban town of Cojímar. He knew the town well; it was where he kept the Pilar, and he was a frequent patron of an eating and drinking establishment called La Terraza, which overlooked the small harbor featured in The Old Man and the Sea (1952), the last major work of fiction published in Hemingway’s lifetime. It won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954, providing a fitting capstone to a great career.

Throughout the 1950’s, the author’s health was declining. Worse, he was losing confidence in himself as a writer. In 1953, on safari in Africa, he and Mary were involved in a disastrous double plane crash, and he received a head injury from which he never fully recovered. It’s also fair to assume that his health and mental acuity were adversely affected by long-term alcohol abuse. People who saw him in the latter part of the decade were shocked by how old and frail he looked compared to the image of the vigorous sportsman and war reporter that had taken root the popular imagination. Still, he was managing to live an intermittently happy life, taking special pleasure in the company of the latest generation of the 57 cats that lived at the Finca Vigía during his decades there. “A cat has absolute emotional honesty,” he famously wrote. “Human beings, for one reason or another, may hide their feelings, but a cat does not.”

3.

The emotions behind Hemingway’s enduring legacy in Cuba click more clearly into focus when you talk to those who knew him when they were young. I spoke to an octogenarian fisherman in Cojímar who’d once been invited up to the Finca Vigía, along with several other young locals, to talk about his daily life and fishing practices, undoubtedly as background research for The Old Man and the Sea or Islands in the Stream. On the way back from his outings in the Pilar, Hemingway would throw towropes to local fishermen, saving them half a week’s wages in valuable gas. Indeed, the author went out of his way to maintain good relations with many working men — taxi drivers, bartenders, fishermen — with whom he was more at ease than the awestruck international visitors who were constantly knocking on his door.

The Cuban government has honored the author’s memory by preserving the Finca Vigía exactly as it was when he left it in the spring of 1960. It’s a profoundly evocative place. Hemingway’s well-stocked bookshelves are exactly as he kept them; the magazines strewn about the tables are all from 1959 and early 1960. His spectacles lie open on a side table; the typewriter where he worked rests on a shelf; several enormous pairs of shoes hang toe-down in a closet rack. The walls of the pleasantly airy and light-filled house display several of his big game trophies, including the actual physical remains of the animals that played starring roles in “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” (water buffalo), and The Green Hills of Africa (kudu). You can see the author’s handwriting on the bathroom wall, where he periodically inked his fluctuating weight during those difficult waning years.

4.

The onset of the Cuban Revolution worried Hemingway — the explosion of a nearby munitions depot broke windows in the Finca Vigía — but according to Carlos Baker’s biography he was pleased in January of 1959, when Fulgencio Batista fled the country and Fidel Castro’s bearded revolutionaries rolled in to Havana. Hemingway was disgusted by Batista’s corrupt dictatorship, and he saw the Revolution as a positive change: “I wish Castro all the luck,” he said. “The Cuban people now have a decent chance for the first time ever.”

He did meet Fidel Castro, in November of 1959, at a fishing tournament west of Havana. The young Revolutionary leader won the tournament, and Hemingway presented the trophy. Castro said that he’d kept a copy of For Whom the Bell Tolls in his backpack during the years of guerilla insurgency in the Sierra Maestra, which must have been thrilling for Hemingway to hear. “I always regretted the fact that I didn’t…talk to him about everything under the sun,” Castro later remarked. “We only talked about the fish.”

5.

At the Finca Vigía, downhill from the main house through shaded gardens, a walkway leads to the author’s voluminous pool. Drained now, it’s a dangerous-looking abyss, the slanting cement bottom painted blue, blown leaf litter piled in the deep end. Just below the pool, where the tennis court used to be, the Pilar rests in dry dock beneath a high tin roof. Bolted to the top of the boat is Hemingway’s custom-designed flying bridge, where he could steer the yacht and stand lookout for marlin, or U-boats. This few square feet of decking, upon which the author spent so many avid hours, is perhaps the place in Cuba where Hemingway’s troubled ghost bleeds through the thin tissue separating the living from the dead most unmistakably. It’s impossible not to visualize him standing there, gazing out over the prow as he steered the Pilar among the azure channels and white-sand keys of the island’s northern coast, as reflected in this passage from Islands in the Stream:

The water was clear and green over the sand and Thomas Hudson came in close to the center of the beach and anchored with his bow almost up against the shore. The sun was up and the Cuban flag was flying over the radio shack and the outbuildings. The signaling mast was bare in the wind. There was no one in sight and the Cuban flag, new and brightly clean, was snapping in the wind.

6.

One of the chief traits of Havana that makes it irresistible to visitors is the city’s elegant decay: the fact that its long isolation from the architecture-purging mainstream of the world economy has preserved a striking carapace of multi-layered history. Havana is a kind of massive time capsule in which, depending on the neighborhood, one barely has to squint to be transported back to the 17th century, the Art Deco 1930s, the 1950s gambling era dominated by the American mafia, and of course the forbidden Soviet Cuba of the Cold War.

It’s ironic, and perhaps fitting, that Hemingway’s single-minded pursuit of vivid real-life experience that he could immortalize in fiction is what led to him to Havana. Because despite his best efforts, the life could never quite match the intensity of the fiction, and that truth may have contributed to killing him. In Havana, the spirit of Hemingway endures, much like the architecture of the city itself, a fading reminder of what was and what might have been.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.