Flip to the back of a new book. What do you see? Blurbs. Line after line of praise, proclamations, and predictions. Tucked in a small corner square is an author’s photo, a passport-size acknowledgment of the face behind the book. Often those faces are hidden inside a jacket flap.

Bring back the book jacket photo.

Bring back those full-page portraits that pronounced I wrote a book, damn it.

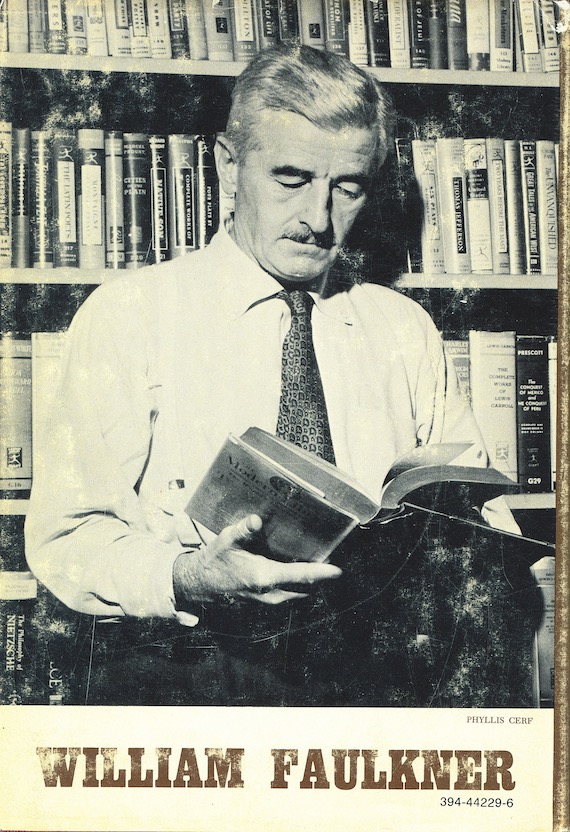

For The Reivers, William Faulkner stands in front of a bookshelf full of Modern Library titles. He wears a tie and suspenders, with The Philosophy of Nietzsche and Cities of the Plain at his back. He doesn’t look at us, but at the book open in his hands.

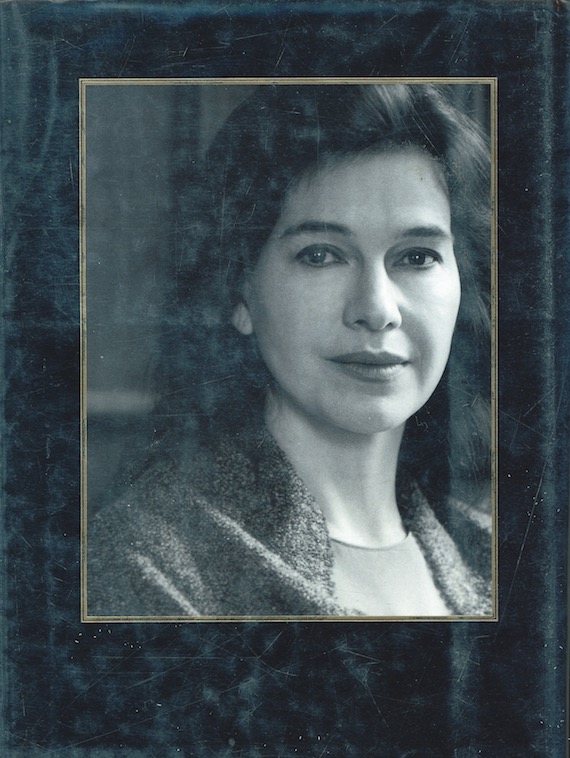

Framed in gold and set against black, Louise Erdrich’s photo for Tales of Burning Love feels pronounced. The novel begins: “Holy Saturday in an oil boomtown with no insurance. Toothache.” You can hear Erdrich, confident yet controlled, spin that yarn for us.

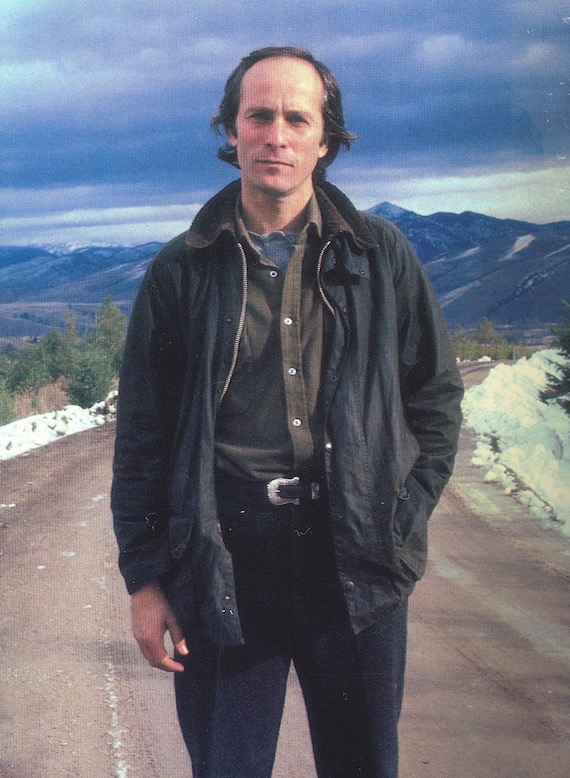

I’m a little afraid for Richard Ford on the back of Rock Springs, his collection of stories. Ford stands in the middle of a snow-lined Montana dirt road, against a backdrop of mountains. He doesn’t seem too concerned, and the pose matches the prose, after all. The first line of the title story is “Edna and I had started down from Kalispell, heading for Tampa-St. Pete where I still had some friends from the old glory days who wouldn’t turn me in to the police.”

A novel is an accomplishment, something to be celebrated. Paradise by Toni Morrison got a fuller photo treatment than Beloved and Song of Solomon, and the author deserves it. Morrison’s countenance tells us: here is a story. Read it.

“Even a selected display of one’s early work,” John Cheever writes in the preface to The Stories of John Cheever, “will be a naked history of one’s struggle to receive an education in economics and love.” Cheever, wearing an open-necked shirt and sport jacket, smiles on the back. He looks pleasantly resigned.

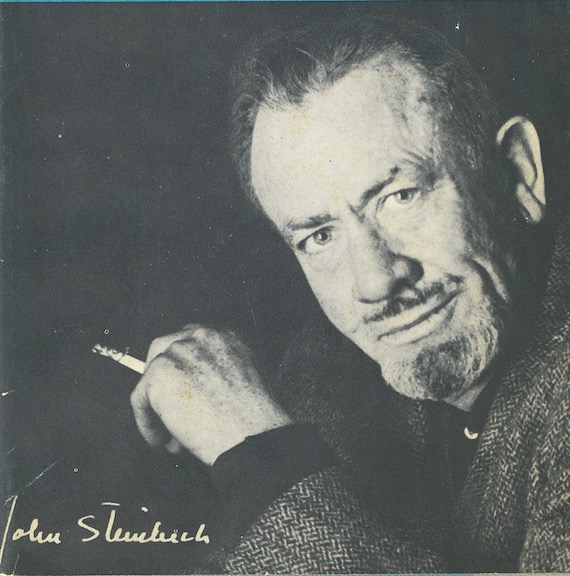

John Steinbeck channels Vincent Price on the back of The Winter of Our Discontent. Appropriate for the novel’s ominous epigraph: “Readers seeking to identify the fictional people and places here described would do better to inspect their own communities and search their own hearts, for this book is about a large part of America today.”

Published in 1992, Susan Minot’s shot on the back of Folly is early ’90s cool: hair up, back, and messed, with an unbuttoned denim jacket. An interesting contrast with a work of historical fiction prefaced by an endlessly appropriate quote from Blaise Pascal: “Man is so necessarily foolish that not to be a fool is merely a varied freak of folly.”

Previously: Edan Lepucki on Marion Ettlinger