1.

Unlike most people, with or without children of their own, I had not come to Margaret Wise Brown by the popular-to-the-point-of ubiquitous Goodnight Moon. Even if I had never read Goodnight Moon (but hasn’t everyone read Goodnight Moon?), it was impossible not to encounter it in every children’s bookstore and airport across the land where it not only existed in its original form but in endless imitation from Goodnight _____ (fill in the blank of the city or state to Good Night Farm, Zoo, North Pole, Ocean, World, Galaxy, and Baby Jesus, to say nothing of parodic spin-offs like Goodnight Goon, Goodnight iPad, and Goodnight Husband, Goodnight Wife. But Goodnight Moon wouldn’t prove to be the mood lure that would have me wanting to enter more deeply into the worlds created by Margaret Wise Brown.

Unlike most people, with or without children of their own, I had not come to Margaret Wise Brown by the popular-to-the-point-of ubiquitous Goodnight Moon. Even if I had never read Goodnight Moon (but hasn’t everyone read Goodnight Moon?), it was impossible not to encounter it in every children’s bookstore and airport across the land where it not only existed in its original form but in endless imitation from Goodnight _____ (fill in the blank of the city or state to Good Night Farm, Zoo, North Pole, Ocean, World, Galaxy, and Baby Jesus, to say nothing of parodic spin-offs like Goodnight Goon, Goodnight iPad, and Goodnight Husband, Goodnight Wife. But Goodnight Moon wouldn’t prove to be the mood lure that would have me wanting to enter more deeply into the worlds created by Margaret Wise Brown.

I found Brown lurking with a start in the pages of a 900–page book on noise by cultural historian Hillel Schwartz. I had invited the scholar and translator to the campus where I teach to discuss his book in a class in “literary acoustics” –a course in which we sought to transform words on pages and so much of what we took about our lives to be self-evident by turning our attention to sound, voice, noise, and silence. Schwartz introduced the students and me to one book in a series of books devoted to listening by Brown, the paradoxically titled The Quiet Noisy Book.

I found Brown lurking with a start in the pages of a 900–page book on noise by cultural historian Hillel Schwartz. I had invited the scholar and translator to the campus where I teach to discuss his book in a class in “literary acoustics” –a course in which we sought to transform words on pages and so much of what we took about our lives to be self-evident by turning our attention to sound, voice, noise, and silence. Schwartz introduced the students and me to one book in a series of books devoted to listening by Brown, the paradoxically titled The Quiet Noisy Book.

It was interesting at the outset to think about the vast mood influence the magic of one of Brown’s books had cast into the nighttime wells of millions of children over a period of several decades and still to this day. Then, to pause to consider how little any reader, be they parent or child, knew about the particular geometry of her life, to say nothing of the scores of books she wrote that haven’t yet enjoyed the same ascendency as Goodnight Moon including her Noisy Book series, or those she wrote under a handful of pseudonyms. Could it matter to our experience of the book to know that Brown didn’t live to see Goodnight Moon thrive, that she died young, at 42 in 1952, exiting life with the kind of boisterous exuberance she was known for: cause of death was a cancan-type kick of her leg into the air following a minor surgery. She died instantly of an embolism. In an equally strange twist of fate, in her will, Brown had named the child of a friend the right to all monies earned by her books should he survive her, but the boy, who never completed high school and who gained a reputation for destroying public property and beating people up, grew up to squander the millions.

At the center of the famous tale was a bunny, and Brown had grown up with bunnies and other animals. As an adult, she once took a bunny on a train with her en route to a date; but, could a reader imagine it? — as a child, she had also skinned a bunny. The houses she lived in were like hutches — in the middle of Manhattan, a cottage that she called Cobble Court; on a ruggedly beautiful island in Maine named Vinalhaven, a former quarryman’s house she dubbed “The Only House.” Brown’s biographer, Leonard Marcus, describes the house as an uncomfortable extravagance: it wasn’t wired for telephone service or electricity and lacked indoor plumbing, but Brown made sure the larder was stocked with “champagne, fresh cream, imported cheeses and other such necessities.” A well served as a fridge, as did the cool, running waters of a nearby brook, from which she might surprise a visitor with a bottle of wine. Rainwater was collected for bathing, and three outhouses were positioned “for the sake of the view”: “a mirror had been nailed to one of the apple trees in the yard, and a pitcher and basin were left out on a battered Victorian washstand. First-time visitors would be surprised on opening the drawers to find the freshly laid supply of scented soaps and toiletries of Margaret’s ‘Boudoir.’” One part of the house brought the outside in through a collection of small mirrors, “each differently framed and made flush with its neighbors.” The mirrors were hung across from a door that opened onto a “sheer fifty foot drop,” and positioned in such a way each to reflect a “different image of the sea” in succession. People finding themselves in the mirrors, would glimpse themselves as “plural.”

I don’t recall which detail from Hillel Schwartz’s work on Brown and noise made me ask him about her romantic life. I only remember a feeling of a life lived differently and athwart, and a desire to draw closer to her, whatever the answer might be. I wasn’t looking to find myself in her, but learning that she’d spent most of her life in a relationship with a woman poet who called herself Michael Strange and who had been the ex-wife of John Barrymore filled me with a perverse delight. Picture this: when Michael was in the mood, she called Margaret “Bun;” when Margaret was in the mood, she called Michael “Rabbit” (those really were their pet names for one another). I loved how the idea of a “childless” lesbian having devised one of the most classic books for children gave the lie to maternity as the only or most natural route to knowing how to be with children. I wondered if hospitals that sent copies of the book home with newborns would discontinue the practice if they knew the book’s author had been queer. Would all those folks who lulled their children to sleep with Goodnight Moon rest easy if they knew the little prayer was birthed by a lesbian consciousness? Might they worry that Goodnight Moon could unconsciously shape a mood realm deep inside the child that might make him grow up gay?

Come to think of it, all of the mood-room makers to have drawn my interest are by coincidence queer insofar as all three — Florence Thomas, Thomas Hubbard, Margaret Wise Brown — lived out of tune with the hum of a neatly domesticating hetero norm. Florence Thomas, I recently learned, and as I’d imagined, enjoyed her days in retirement alone with her cat, her garden, and a basement studio where she carved abstract art out of wood. “‘I’m a cat person,’ Florence Thomas told a local reporter in 1971, ‘So I am really fondest of ‘Puss and Boots.’” “You have to know how to be a scavenger,” she said, referring to the suite of materials used in her scenes. “It’s much easier now since we have plastic flowers and leaves. I used to bring live things from the garden.” Though retirement would give her time “to renew old friendships” — she was planning a major trip to Australia and New Zealand with one friend — she explained she wanted to work on her garden first. This wasn’t a garden-variety garden providing flowers for the table or tomatoes for a stew. Spanning one half-acre, it was a form of applied dedication by a specialist-eccentric: Thomas had cultivated one hundred varieties of rhododendrons. She continued to make 3-D constructions, but now by way of what was known as the Personal View-Master camera: a device that people could use to make View-Master reels with images they themselves took, based, that is to say, on their own lives.

Hubbard wasn’t exactly a solitary soul, but he lived at an apparent distance from his wife, who has been described as emotionally unwell, devoting himself to his students, his art, and his summer travel in turn.

Brown had experienced attachments to other women and a near marriage to a man before she met Michael Strange. Unfortunately, her relationship with Strange wasn’t, in the long term, a happy one. Strange comes off as abusive in the end, with Brown the ever-pining and unfulfilled lover. One of numerous painfully poignant junctures in Leonard Marcus’s account of their relationship has Brown hiring a lobsterman to build a special house just for Michael Strange near to Brown’s “Only House” on Vinalhaven. Since Strange rarely joined her there, perhaps Brown thought designing a “Picture Window” using an ornate picture frame she’d found in a Rockland antique shop trained on a spruce forest would do the trick. But she was wrong. Nevertheless, an unconventionally attuned Brown was involved in experiments in living and in writing all her short life — having been the literal voice to prompt Gertrude Stein to compose a children’s book, with the result being Stein’s 1939 The World is Round illustrated by the same artist who pictured Goodnight Moon, Clement Hurd. Brown’s Noisy Book series, which came into print around the same time, grew directly out of her work with Lucy Sprague Mitchell, founder of the Bank Street School whose experiments in early childhood education in the early 20th century included encouraging children to be noisy rather than disciplining them into silence. Many of Brown’s books in progress were tried out, so to speak, on children at the school.

Brown had experienced attachments to other women and a near marriage to a man before she met Michael Strange. Unfortunately, her relationship with Strange wasn’t, in the long term, a happy one. Strange comes off as abusive in the end, with Brown the ever-pining and unfulfilled lover. One of numerous painfully poignant junctures in Leonard Marcus’s account of their relationship has Brown hiring a lobsterman to build a special house just for Michael Strange near to Brown’s “Only House” on Vinalhaven. Since Strange rarely joined her there, perhaps Brown thought designing a “Picture Window” using an ornate picture frame she’d found in a Rockland antique shop trained on a spruce forest would do the trick. But she was wrong. Nevertheless, an unconventionally attuned Brown was involved in experiments in living and in writing all her short life — having been the literal voice to prompt Gertrude Stein to compose a children’s book, with the result being Stein’s 1939 The World is Round illustrated by the same artist who pictured Goodnight Moon, Clement Hurd. Brown’s Noisy Book series, which came into print around the same time, grew directly out of her work with Lucy Sprague Mitchell, founder of the Bank Street School whose experiments in early childhood education in the early 20th century included encouraging children to be noisy rather than disciplining them into silence. Many of Brown’s books in progress were tried out, so to speak, on children at the school.

The Noisy books, Brown explained, “‘came right from the children themselves — from listening to them, watching them, and letting them into the story when they are much too young to sit without a word for the length of time it takes to read a full-length story to them. I mean three- and two-year olds.” At the center of the series is a little black dog named Muffin who stands in place of a child — one imagines the child-reader identifying with him — but who, on account of his being a dog, has a keener sense of hearing than a child. Or does he? The books are meant to meet children in that time before they’ve come to use language fully to mediate desire and their world, that period when looking hasn’t yet replaced listening as the form of reading, where letters aren’t yet yoked to sounds but float, one form among others on a page splashed with Leonard Weisgard’s bright colors and Brown’s colocation not just of words bound to meanings but of phonemes’ clattering in imitation of sound.

If Gertrude Stein famously discovered the difference between sentences and paragraphs by listening to the rhythm with which her dog lapped the water in his bowl, Margaret Wise Brown understood the equation in reverse when she included dogs among her listener-readers. A dog can train a writer to make prose; and, a writer can write a book that a dog can understand. “Dogs,” Brown wrote, “will also be interested in ‘the Noisy Books’ the first time they hear them read with any convincing suddenness and variety of whistles, squeaks, hisses, thuds, and sudden silences following an unexpected BANG.”

Here I am, a dogless adult, tethered to and transfixed by Brown’s protagonist dog. The play-space she creates for him and invites us to enter in her books isn’t exactly a-brim with frolic and jaunt, a run in the park, a pat or a pant, the tossing of a ball before being tucked in with a biscuit and warm milk for the night. These aren’t easy or straightforwardly narrated books. They are tantalizingly difficult; most have the riddle of sound at their center; all are marked by absence, for isn’t it the nature of sound to emanate from the object world but remain detached from it; to seem to reside within an object but not be traceable to it; to exist as a solid experience of sense but to remain ungraspable, sometimes unlocatable, at heart, ephemeral?

Meaningful and meaningless sounds were the bases of our moods — possibly the earliest molds for the form a mood could take — and sound is mood’s analog.

In The Quiet Noisy Book, Muffin is awakened by a “very quiet noise.” “What could it be?” the narrator asks, then provides a set of answers in the form of questions whose examples are beyond audition, or imaginary: “Was it butter melting?” “Was it an elephant tip-toeing down a stairs?” “Was it a skyscraper scraping the sky?” Teasing the limit of our senses to meet the reach of our imagination, gathering into a book-as-net all that coexists simultaneously with us and beyond us, offering a promise of presence — the blank filled in — if only we could be willing to listen hard enough, the book answers each possibility with the word “no,” without at the same time canceling its belief in the possibility that what Muffin could be hearing was “a fish breathing,” say.

What do we wake to? What is the sound that’s waking Muffin up? It’s something very quiet, but there. It’s “quiet as a chair. Quiet as air.” It’s something Muffin knows, but do you know what it is, dear reader? By now you could be terrified or mesmerized or both, when, splash, it is the sun coming up. The sound of the sun coming up is accompanied by conventional harbingers of joy — roosters crowing and such — but Brown also leaves the child — and the adult reader — with puffs of cloud heavy with mystery, my favorites being, it was the sound “of a balloon about to pop,” and “it was a man about to think.”

Here Brown had gifted me the finest definition of a mood, and one defying explanation. Mood: it was the sound of a person about to think. What qualities inhere in the sound of a person about to think? Does thought really admit of pause? What form of silence have we here, for doesn’t the “about to,” though yoked to sound, imply an absence of sound? A soundless sound?

Philosophers of silence spoke of silence as its own active presence, not merely a negation of sound. Of brusque or smooth silences, of silences yoked to utterance, and requisite to language’s meaningmaking capacity, and silence as its own live phenomenon, with its own temporality, independent of sound. Of silence as predictive of the type of utterance to follow, of rhythmic silence, silence as the place of anticipatory alertness, and silence that serves as an end point or terminus, a concluding silence. Silence that casts a spell, and silence that lifts a spell. Certainly, there is no such thing as silence pure and simple, and if any of us were asked to generate types of silence, we could come up with enough examples in an instant to fill a page — just now, radio silence; the silence enjoyed between intimates; awkward silence; and how about the silence that pervades the experience of reading? Does that bear any resemblance to the sound of a person about to think?

Margaret Wise Brown is the person whose picture books ask these questions, not I, and when she translates the “new day” in The Quiet Noisy Book into the dawn of life’s unanswerables, she opens her reader to possibilities of heaviness or light, of greeting the unknown with a mood of curiosity or hiding under the covers depressed by the prospect of pondering.

If we equate the sound of a person about to think with a form of soundlessness, that’s only because, as adult readers, we think of thought as word-bound, a kind of talking to oneself, and sound, therefore, as one sign in a system of language, like the space between words, say. But what if the sound of a person about to think were a tone or air, a vibration or an atmosphere that thought depended on, no matter the form thought took; what if it was understood to be a presence rather than an absence, albeit one we might not be able to translate into words?

What I notice about the books in Margaret Wise Brown’s Noisy series is how, in each of them, she confides in absence, allows for it, enfolds a reader in it even: she makes absent presences a field of play. For, whether it is The Indoor Noisy Book, The Noisy Book, The Winter Noisy Book, The Seashore Noisy Book, The Summer Noisy Book, or The Country Noisy Book, to name a few, there is always something menacing, askew, uncanny, inexplicable, in excess, or ghosted to contend with or consort with. It’s that same quality that provides a mood for or to childhood but that is forgotten or covered over in adulthood, in which case, adult moods are a form of the comforting blanket that one had lain beneath when such stories had been read to one; they are the cover for a more mystifying cloudscape forgotten but ever-hovering.

What I notice about the books in Margaret Wise Brown’s Noisy series is how, in each of them, she confides in absence, allows for it, enfolds a reader in it even: she makes absent presences a field of play. For, whether it is The Indoor Noisy Book, The Noisy Book, The Winter Noisy Book, The Seashore Noisy Book, The Summer Noisy Book, or The Country Noisy Book, to name a few, there is always something menacing, askew, uncanny, inexplicable, in excess, or ghosted to contend with or consort with. It’s that same quality that provides a mood for or to childhood but that is forgotten or covered over in adulthood, in which case, adult moods are a form of the comforting blanket that one had lain beneath when such stories had been read to one; they are the cover for a more mystifying cloudscape forgotten but ever-hovering.

There is a kind of ultimate silence, of course, that, if we try to “think” it, fills the mind with existential dread — the blotting of consciousness, the death-in-store that would jettison us into, well, I can’t think of a better figure for it than “outer space.” Celestial music or the music of the spheres must just be something humans have devised to console themselves with when confronted with the inconceivable absoluteness of the silence that is death. Mood is that silence momentarily animated.

2.

In several of the Noisy books, Muffin’s eyesight or some other aspect of his sensorium is compromised so that he has to rely more fully on his capacity to listen. In The Noisy Book, he’s gotten a cinder in his eye and is required to wear a blindfold. In The Indoor Noisy Book, he has caught a cold and is forced to stay inside making him more acutely aware of the noises in the house. In The Seashore Noisy Book, he is disoriented by the fact of his hearing, for the first time, the sounds of the ocean. As the book nears its end, he hears a splashing sound, and, as always, we are invited along with Muffin to try to attach the sound to its source: “Was it the sun falling out of the sky?” “Was it a sea horse galloping?” Earlier, we’re asked to listen for the light of moon and stars on water. The “answer” to the splashing is that Muffin has fallen out of the boat and it is his own flailing that he’s caught in the sound of. He began by falling into a mood — the mood of the sea — and ends by being rescued from his nearly drowning there. This particular meta-ending is just one instance of the mystery of sound — and by affiliation, mood — being answered by a scenario of oddly proportioned dimensions in which nothing is resolved but where we are asked in effect to squeeze the large round ball attached to a scary clown’s nose.

The end of The Noisy Book might be the most delightfully perverse in this respect. Here, blindfolded Muffin hears a squeaking whose source he can’t identify. Neither a garbage can nor the house nor a mouse nor a policeman, the answer is “a baby doll / And they gave the baby doll to Muffin for his very own.” The problem, or pleasure, for a reader, though, is that the anthropomorphizing has Muffin playing with a facsimile of a human rather than with a doll in the form of a diminutive dog — a puppy doll, and that the illustration shows the doll to be nearly twice Muffin’s size. He can barely hold the doll, but he’s propped himself, sans blindfold now, as if posing for a snapshot. Muffin and the reader in their collaborative investigations of sound and mood seem to have won the booby prize.

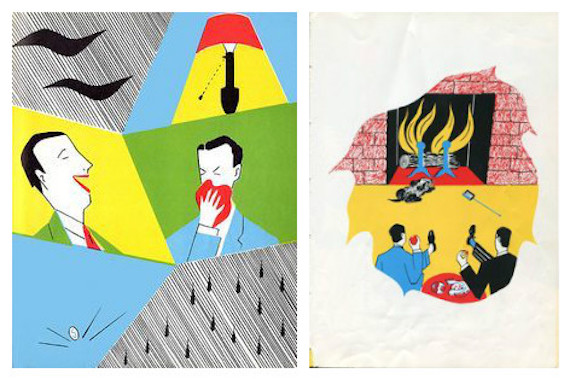

The Winter Noisy Book might broach the most uncanny territory of all once we realize it’s Brown’s version of Muffin Had Two Daddies. Winter has come; night is cold, and still, beyond the windows; stark, black branches rattle against the windowpane. Muffin hears a thud thud thud scrunch scrunch scrunch — what was that? Rather than provide her usual series of playful speculations, Brown works together with her illustrator — this time an abstract painter other than Weisgard, Charles G. Shaw — to produce a frighteningly stark page. The illustration shows an empty dog collar and leash, and a shade drawn against the darkness in a furniture-less room. One sentence is spelled across the white floor of the room. As answer to the question of the scrunching, it could describe the entry of a sci-fi menace: “The fathers were coming home.” Does the empty collar mean the dog has fled or that the dog has died? More benignly, could it mean the fathers are the ones who will take Muffin out for a walk? The ominous mood is dispelled — the blank of the page filled in — by the introduction of a perfectly normal-seeming domestic scene comprising two men. They produce sounds that Muffin listens to, like laughter and the dropping of a nickel, the turning on of a light, and the b-r-r-r-r of a shiver before they stretch their legs in front of the roaring fireplace where they sip cocktails and crunch on celery. Muffin is merrily spread on the rug before his bachelor fathers — one clad in neatly striped pants, the other, solid blue.

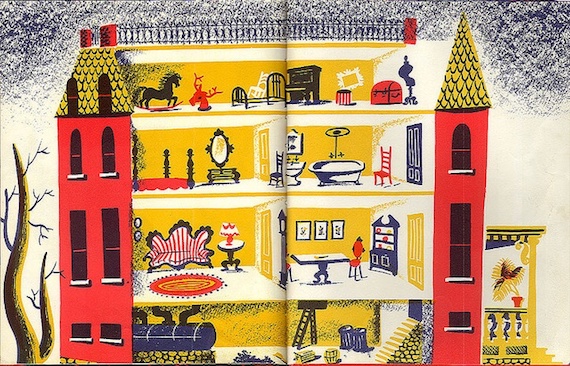

Leonard Weisgard, who had been a dancer and a Macy’s window display designer before he turned to children’s book illustration, mastered the magic of minimalism in the Noisy books. The palette is simple, relying sometimes on no more than four colors in the course of a book, including the noncolors, black and white, especially in combination with primaries. A page could turn entirely yellow, daylight reduced to a trapezoid of blue against red. He arrives at images — the shape of icicles, for example — by subtracting rather than filling in, or by cutting out and pasting in. If I find myself wanting to roam around inside an illustration, is that the same as reading?

The endpapers of The Indoor Noisy Book hold my attention the way the interior of a doll’s house once had. For a two-page spread, he’s cut one side of the walls out of Muffin’s four-story house so we can climb the small ladder in the basement through a hatch to arrive in the dining room whose table sits below a Victorian tub in the bathroom on the floor above it, which sits beneath the most interesting room of all: the attic. There’s a bed frame and an equally empty, though ornate, picture frame. There’s a dress frame with exaggerated curves. A bandbox and a dome-lidded trunk. A taxidermied moose head. There’s a piano.

Is the power of the drawing — see how it draws me even now, drawing my adult eye, compelling me to redraw it by way of words — fueled by nothing more than reminiscence — just one more instance of a version of 3-D paper cutout houses enjoyed in childhood? When a mood space is activated by a work like this, we are put in contact with something ever present but impalpable. It’s never so simple a thing as a reminder of or a return to something from our past; it’s more a how than a what.

There was a sentence like a conundrum that appeared in Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht’s work on mood that I also wished to understand and most definitely felt I was experiencing. Describing what happens when literature creates a mood, Gumbrecht made a distinction thus: “For what affects us in the act of reading involves the present of the past in substance — not the sign of the past or its representation.” I’m not compelled by Weisgard’s illustrations because they bring my past back to me by pointing to it in replica but because something has been made possible in the readerly transaction of color, line, and consciousness that puts me literally in contact with a piece of a reconstituted atmosphere as if to say I once was in that dream but forgot I’d never left its precincts. Now I not only recognize its outline but also feel what it is to be buoyed inside its envelope. It’s not a forgotten place but a place where I always am — part of my mood repertoire — but which I fail to see.

While Weisgard’s elaborated interior might seem like just one more iteration of a repetition of examples — enter a return to an already-scripted View-Master — there were other aspects of his illustrations for Brown’s books that turned a key to unlock a mood and that were much less legible. They were not at all “representational.” These were absorptive planes (pure blots of color, where the feeling of the paper as recipient of a hue was as important as the fact of color itself), and stencils.

Numerous of the images in The Indoor Noisy Book are finely dotted or shaded as though they were applied through screens or with sponges onto the white page below rather than fully filled in, and bunches of tiny flecks of color mist around their edges like the scatter left by a spray-painted stencil. Maybe a child is meant to read such touches as a sign of its maker having fun: “These pictures are ones you too could make,” the speckled fringes say, “some afternoon of arts and crafts.”

For this adult reader, it matters that I touch the page when turning it, and when I do, I’m suffused with a smell of sour milk and hay. White-colored goo had been applied to a piece of bright red particleboard, four by four inches square. Had we been given sprayers or had the adults sprayed our hands? You pressed into the board, painted the white goo on, and what remained as an absence but also as an imprint was your child hand. Overly warm milk in a small waxen carton probably was meted out to us after nap time in kindergarten like dribbles of white into the mouths of mewing kittens. But the “stuff” we used to “make our hands” that day was milky, too, and sour smelling. The hand left on a block of red detached from a body was meant as a gift to our mothers, but it wasn’t something I wanted to give to mine. The hand lay in a drawer as a shadow self. It was the hand from a body that could only be described as “bleating.” If this wasn’t the stuff of an originary mood, I don’t know what else could be. And it was immanent in the quiet noisy books of Margaret Wise Brown.

Stencils could be a form for mood itself: there was always something missing from them; a stencil was a means, and its end. Would the stenciling in The Indoor Noisy Book create a mood no matter the particular reader’s relationship to stencils, then? Or in order for it to do its work, need it be tied to a remembrance of stencils past? To me, it seemed struck from the same granules as a mood that I harbored, one part quavering voice, one part shadow.

3.

Stencils can be found in caves dating to 10,000 B.C. And guess what they depict? Hands. Entire walls with nothing but hands like paw prints as records of human yearning. Early man, delighted with a technique of missing and finding himself at the same time. Hands as outlines feeling for something in the rock. Not pushing it upward like Sisyphus but transmitting or receiving warmth from it. Then there were those uses of hands that magically—with no more than a set of stick legs here, a wattle there—transformed the outline of palm and fingers on a page into a turkey. I wonder if we effected such magical transformations in the same week that we spray-painted our hands or in the week following. No doubt we were also instructed to give our turkey-hands to our mothers.

In even earlier childhood, when naming is the game but not yet reading, you might be placed before the sort of “puzzle” made of wooden figures that you are meant to fit into shapes cut out for them. The shapes — either abstract or figural — have knobs attached to them that make them seem like lids or doors. No doubt the point of such puzzles is to aid a child in the development of hand-eye coordination while at the same time teaching her words. Assuming that is a skill I’ve mastered, what kind of pleasure could such a puzzle hold out for me now?

I bought one such puzzle at a flea market because I had a hunch it belonged with the View-Masters and picture books in a cupboard marked “the mystery of mood.” I also found it aesthetically pleasing: in its world, a duck could reside in the same row as a clock, a house was the size of a crow, and a cat that of a sailboat. Each thing was unstuck from any context and returned to its thingness: one purely red chair; a single boot without the need for a foot or mate. I felt it had something to teach me, but I also quite simply enjoyed it: placing the wooden tree snug in the slot suited only for it and it alone, doing the same with the dog, the hen, and the jug must work to quell the chaos in any adult life.

The principle behind the puzzle was as riddled with absent presences as any book by Margaret Wise Brown and just as rife with a mood of earliest reading. Fitting each figure into its slot, you earn the prize of getting something right, case closed. But you also cover something over; each time you remove a form, something is revealed: hiding inside each home for a form is its word. It’s easy to get the words wrong — one reason no doubt that the manufacturer called the puzzle Simplex, brother of complex: instead of “boat,” the slot yields “yacht.” Where I recognize a creamer, it tells me it’s a “jug.” Instead of a crow, it offers the word “bird.” An obvious Christmas tree is simply a tree. The figure meant for a slot whose inner wall reads “teddy” is missing from this puzzle. I think if I saw it, I’d call it a bear.

Learning to call things by their right names; imagining words as entities, or answers, that hide inside things; trading in the feel, and the shape, of the thing for its word so that you can eventually advance from puzzles to reading: our moods lurk in the interstices, for our mood is the story no one asked us to devise when presented with the shape of the thing. It’s the missing link between the word and the thing, and it’s also the cloak that shrouds the word in mystery. It’s the shape left inside the toy box cut off from the hand that held it.

It was the sound of a balloon about to pop.

Reprinted with permission from Life Breaks In: A Mood Almanack. Published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2016 Mary Cappello. All rights reserved.