Danielle Dutton is a writer, editor, and publisher who might shift the way you read. Author of Margaret the First, SPRAWL, and Attempts at a Life, her writing is compact and quick as it contemplates the strange banalities of domestic life. Her prose finds wonder in the uniformity of the suburbs, or the particularities of 17th-century aristocratic life. It’s funny and full of strange consequence.

Dutton also runs Dorothy, a publishing project, one of the best independent presses in the United States. Dorothy is dedicated to “works of fiction or near fiction or about fiction, mostly by women.” Dutton works on all components of each Dorothy release, including curation, editing, and design. In just seven years, with writers like Renee Gladman, Joanna Walsh, Joanna Ruocco, Nell Zink, Amina Cain, and more, Dutton has brought together the work of some of the most electric voices in contemporary publishing.

Dutton also runs Dorothy, a publishing project, one of the best independent presses in the United States. Dorothy is dedicated to “works of fiction or near fiction or about fiction, mostly by women.” Dutton works on all components of each Dorothy release, including curation, editing, and design. In just seven years, with writers like Renee Gladman, Joanna Walsh, Joanna Ruocco, Nell Zink, Amina Cain, and more, Dutton has brought together the work of some of the most electric voices in contemporary publishing.

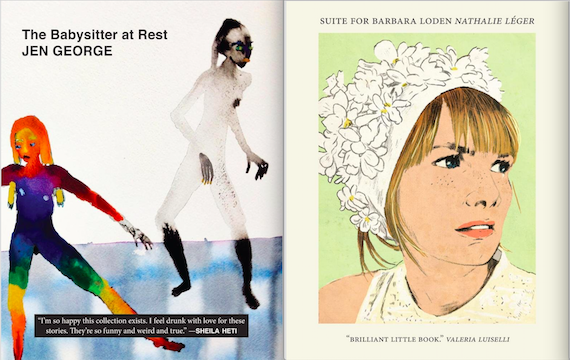

Each Fall, Dorothy publishes two new books simultaneously. This year, Dorothy continues its pattern of innovation, with genre-bending French writer Nathalie Léger and out-of-nowhere wunderkind Jen George. Léger’s Suite for Barbara Loden seamlessly blends biography, memoir, film criticism, and auto fiction, as it contemplates the star of a 1970 art-house movie. George’s The Babysitter at Rest is a hilarious and one of a kind story collection that has already earned the adoration of writers like Ben Marcus, Sheila Heti, and Miranda July.

I wrote to Dutton to ask her about this year’s Dorothy releases, and her work as a curator, editor, writer, and reader.

The Millions: How did Suite for Barbara Loden and The Babysitter at Rest come into your hands? What was the process like of editing these books, and working with Jen George and Nathalie Léger (or Léger’s translators)?

Danielle Dutton: In the case of Jen George’s The Babysitter at Rest what happened was fairly straightforward: I read her story “The Babysitter at Rest” in BOMB (it had been selected by Sheila Heti for BOMB’s 2015 Fiction Contest), and I thought it was incredible. Totally unlike anything I’d read. After about three paragraphs I could feel my hands getting shaky. And this is very often the case, that it’ll take only moments for me to sense that I’ve found the right next book — when this is happening, in those rare and wonderful moments, I actually feel somewhat physically unwell. It’s like I’m literally being overwhelmed by what I’m reading. So, that’s one way I know I want to publish a book: vague nausea. Anyway, I got in touch with the editor at BOMB, who forwarded a message to Jen, for whom my interest was, of course, totally out of the blue, and the whole thing went from there.

With the Léger, Stephen Sparks, who manages San Francisco’s Green Apple Books on the Park, and is an incredibly smart reader and one of our most trusted advisors, put us in touch with one of the book’s translator’s, Cécile Menon. Essentially, he recommended us to her and her and the book to us.

In terms of the editorial process(es): with the translation there wasn’t a ton to do. We chose to Americanize spelling, and we did have a few lines here and there that we went back and forth about with Cécile and her co-translator Natasha Lehrer, but the book was very beautiful and basically ready to go (it had just been published in the U.K.). We worked more with Jen. She sent us a number of stories and we whittled it down to the five you see in the book, and then we worked with her on them, arranging and re-arranging, laughing — the raw material of Jen’s brain continually amazes me. Even her emails make me laugh. The process was, I think, really productive, collaborative. It’s been a delight getting to know Jen and getting to see her see her first book enter the world.

TM: The books that you write and the books that you work with at Dorothy tend to have levity — often a sense of humor — in common. What draws you toward lightness in writing? What’s it like to edit humor in other people’s work?

DD: That’s an interesting question, or series of questions. My first thought is that, editorially, we generally leave the humor alone — it’s either there or it isn’t. It’s more often what’s around the humor that might need attending to, the stuff that allows the funny parts to be funny, unburdened, or as you put it, light. But humor is one of those things like voice, if it’s good it’s because it doesn’t sound like anybody else, and then why would you want to mess with that.

TM: You used to work as a book designer at Dalkey Archive Press. Are you involved in design at Dorothy, too? What are your ambitions in the way you design books? What was it like working on the design of this year’s Dorothy books?

DD: Yes, I do all the design at Dorothy. I think the aesthetic of the press has a lot to do with my limitations as a designer, honestly. Essentially, I am not a designer. I wasn’t a designer when I got to Dalkey, even though I wound up being the book designer there for several years. Minimal was key! I’m actually quite pleased with some of the covers I managed to do there — the covers of both Édouard Levé books, for example, or of Mina Loy’s stories and essays. And I think — I’d like to think — I’ve found a way to make my limitations work at Dorothy as well, though the aesthetic I’ve developed with Dorothy is very different from the Dalkey stuff.

The first thing I do with each cover is find the right art. The art is my focus. I generally manage it by looking all over everywhere, scouring art school tumblers, raiding friends’ Facebook photo albums, just looking all over, really, hoping to find a piece that matches the writing’s energy. I don’t like a cover to be overly illustrative, or literal, but more collaborative with the text. The exception, actually, is the cover of Suite for Barbara Loden, which is an illustration of a still from Barbara Loden’s film Wanda. But something about it being an illustration of a still left space. It still felt open, suggestive, like a sketch.

TM: I was planning to ask you about your great new novel, Margaret the First, but then I realized that you haven’t been asked in interviews about your other new book, Here Comes Kitty: A Comic Opera. Here Comes Kitty is a narrative collage book constructed by you and Richard Kraft. What was it like collaborating on a book? How did you “write” it?

TM: I was planning to ask you about your great new novel, Margaret the First, but then I realized that you haven’t been asked in interviews about your other new book, Here Comes Kitty: A Comic Opera. Here Comes Kitty is a narrative collage book constructed by you and Richard Kraft. What was it like collaborating on a book? How did you “write” it?

DD: Here Comes Kitty is really Richard’s book. He’s a visual artist and he had this series of collages he was working on based out of a Cold War comic book called Kapitan Kloss, which is about a Polish spy infiltrating the Nazis. Richard basically exploded the Kloss narrative with all these bizarre and wondrous intrusions: from Amar Chitra Katha comics of Hindu mythology to underground porn comics like Cherry to just a bunch of bunnies. As he was working on it, he decided it wasn’t quite chaotic enough, I guess, and he contacted me and asked if I would write a text of my own to accompany the images. Our idea was that the images and the text would be in some sort of conversation but neither would attempt to explain the other. To echo my answer about design above: the relationship would be more suggestive than illustrative.

Ultimately we decided (out of a shared love for the collaboration between John Cage and Merce Cunningham) to work separately, each thinking about the other, wondering what the other might be up to, but not knowing, just sort of trusting it to work out, and also being interested in whatever discordant notes might arise. I actually did look at some of his earlier work, as inspiration, to find the tone …and, conversely, Richard knew my book SPRAWL very well. So, yeah, for most of the time we worked with or toward each other remotely — one in Los Angeles and one in St. Louis. The result is, as we’d hoped it would be, a cacophonous book that is sort of rhyming and riotous at once.

TM: Between being a publisher, professor, writer, mom, etc., it’s incredible that you still seem to manage to find time to read. What are your strategies for carving out reading time?

DD: The vast majority of my reading is for teaching or for Dorothy. My strategy for fitting in other reading is pretty dull: I read a lot in the summer. For a while I was reading non-work stuff before bed each night (a long stretch there with Angela Thirkell novels), but I’ve slipped into the habit, at this medium-to-late stage in the semester, of watching TV at bedtime instead.

TM: Do you put books down? Or do you finish what you start? How do you prioritize your reading (beyond teaching and Dorothy)? The Angela Thirkell novels, for example — what kept drawing you to them?

DD: I do put books down, yeah, all the time. I’ll put them down after one page. That’s harsh, and it means I probably miss out on work I might appreciate, but if I’m not immediately interested in the writing it’s hard to justify the time. The Thirkell books are an odd exception. The writing isn’t great. There’s also a certain amount of problematic politics in them (they’re from the 1930s and ’40s). I started them because they’re a series set in the English countryside and I was looking for something easy, bedtime reading. That’s not what I’m normally looking for when I read, but I was feeling stressed out and wanted pleasant little stories about mostly happy people. I did actually grow to admire them more over time. There’s a wonderful sense of ease about them. This sometimes means the books feel too loose, or repetitive, but also they don’t feel labored. It doesn’t feel as if Thirkell was wringing her hands over them, and for some reason I find this refreshing. It feels a bit free.

TM: Seven years in, what’s the hardest part of running Dorothy?

DD: It’s definitely just finding the time.

TM: What’s the most rewarding?

DD: The money and power and fame! Also I really like working with these strange, brilliant writers.

TM: What’s something you’ve read in the past year that you’ve loved?

DD: Sylvia Townsend Warner’s Lolly Willowes: Or the Loving Huntsman

DD: Sylvia Townsend Warner’s Lolly Willowes: Or the Loving Huntsman

TM: What’s something you’re looking forward to reading, but haven’t yet?

DD: Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy and Nan Shepherd’s The Living Mountain.

TM: In the classroom, what’s a book that you love teaching, and why do you love teaching it?

DD: Just this semester I taught Marguerite Duras’s The Lover in a new course on desire, and it was incredibly satisfying, a very rich conversation, because it’s such an open text, there’s so much to wonder at — the politics, the way Duras writes sex, the way desire is enacted structurally. And then one of my favorite short stories to teach is Stanley Elkin’s “A Poetics for Bullies.” It’s hilarious, for one thing, but also it gets students to see what you mean when you harp on about how a character is made up of language, or what you mean when you say that there should be action in the writing itself.