It’s not hard to see the newspaper comic strip is dying. While the superhero comic eats Hollywood, and the Maus–like graphic novel wins awards that used to go to straight fiction, the unfussy, once-a-day comic strip wastes away in pop cultural exile. Partly, this is due to the sad state of newsprint, which checked into hospice a long time ago. Partly it’s a consequence of old strips being available for free. Yet if comic books and graphic novels were somehow able to adapt — even though up until recently they were just as tied to the page — it stands to reason that comic strips can do the same thing. For a while it seemed that webcomics might revive their ubiquity. But in spite of their successes, no one has figured out how to replicate the security of the old syndicates.

For me, as a guy whose vocabulary came largely from Calvin and Hobbes, it’s been painful to watch comic books, graphic novels, and video games — all of which were once seen as mainly for teenagers and children — accrue new popular relevance while comic strips wither away. In the ’80s and early-’90s, comic strips went through a renaissance, showing their readers what was possible at seemingly the last time they could do so. Iconic series like Doonesbury, formerly unique in their roles, got real competition in the sphere of political satire, while offbeat peers like The Far Side netted fans like Robin Williams and Jane Goodall. I can still remember hearing jokes about academics who needed cutouts on their doors to get tenure. In line with new free-market ethics, licensing multiplied tenfold, inundating America with stuffed animals, calendars, and toys. You saw just as much comic strip fandom as you did more traditional geekery. The nation, it seemed, could not get enough of the funny pages.

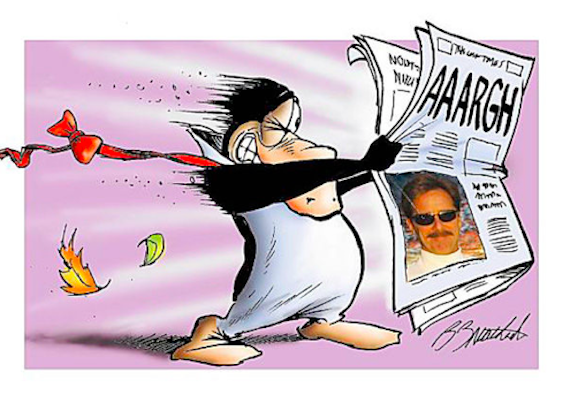

So when I found out, via coverage in The Times, that all-new Bloom County strips had suddenly popped up on Facebook, I felt ecstatic in a manner best associated with lost sleds. On the first new post, old fans like me got nigh-messianic in the comments, implying through over-the-top praise that reviving Bloom County is a public service. In its last couple of years in the papers, you see, the strip featured lots of Donald Trump, which has led many people to suggest that creator Berkeley Breathed is a psychic. I can’t say I endorse this theory (though I do think it can’t be ruled out). What I can say is that it feels necessary in a way its competitors don’t. Regardless of how interesting Doonesbury can be at its best, its impact has always been curbed by a bone-deep Yalie dryness. Only Bloom County offered real succor from the garbage in the news.

Why is Bloom County so loved in comparison to its peers? Why is it immune to the decades-old baggage of its medium? I believe the answer has to do with its treatment of whimsy. In the marketer’s argot, “whimsy” is a vague, weaselly term, one that hints at a childish quality adults are expected to pine for. In its normal, most common form, it means a brand (or at least a person operating like one) is attempting, ironically or not, to reproduce in a subject a time of structured ignorance, to co-opt a memory of trust and naiveté. Because it’s usually easy to spot when someone does this, most of us find it jarring to see, for example, cartoons in SSRI ads, or to hear great songs from our childhood repurposed to sell expensive cars. Few react well to the knowledge that someone wants you to know less. Because of that, it’s easy to think of whimsy as inherently patronizing, as a quality that drains whatever it touches of all value.

That’s a shame, because there’s no reason an artist can’t use it effectively. To get whimsy right — to harness its mood as an asset — an artist must accomplish two things: one, make sure her aesthetic is appealing, and two, show respect for her audience. She needs to conjure up a sense of basic silliness while never treating her readers like easy marks. To strike this balance with any degree of consistency, every joke or moment of humor — no matter how dumb or juvenile it appears on the surface — must clearly rest on a bedrock of genuine gravity. The artist cannot be childish without bringing some pathos into the mix.

I can’t think of a better example of success in this regard than Bloom County. Although it took zaniness to new heights, it always showed that political madness has consequences, and it never left its readers in the dark about the stakes. In what may have foreshadowed certain recent White House Correspondents Dinners, it showed its worth, again and again, by angering the right people at the right times.

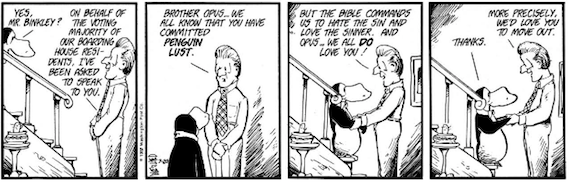

You see this clearly in a plot line aimed at televangelism. When the slobbering, mute Bill the Cat — a character designed as an outright spoof of Garfield — suddenly finds himself infused with born-again fervor, he transforms into the clean-cut pastor Oral Bill. He gets a show on national TV, develops a large local following, and soon infuses the residents of the town with odd, fake smiles and canned lines. Then, with no impetus apart from divine revelation, Oral Bill takes issue with the presence of penguins in Bloom County. He declares that “penguin lust” is a threat to the morals of the nation. In the space of a few days, Opus discovers that he’s been abandoned by his friends, and that, amongst his new enemies, most want to send him into exile. He leaves town on a Greyhound bus with no destination in mind. The fallout of bigotry is palpable here — Opus wouldn’t come back for months. Anyone who reads this understands immediately what a person like Jim Bakker was selling.

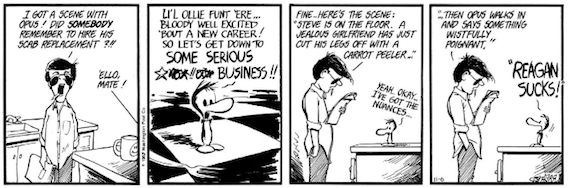

Throughout its run, Bloom County stayed abreast of petty, Washingtonian scandals, and there were even a few times when its critics bolstered its own points. The most well-known example of this was a 1987 brouhaha in which the Miami Herald pulled a strip with the phrase “Reagan sucks!” In the eyes of many readers, Bloom County diehards or no, the Herald’s unpopular decision was a form of Pravda-like censorship, a view the paper rebutted in a long back-and-forth on its letters page. Yet few people now remember the in-strip context of the quote. In the ’80s, New Deal labor was going the way of New Coke, and the characters in Bloom County illustrated this by going on strike for a pay raise. The in-world publisher, W.A. Thornhump, brings in ersatz replacements, one of whom goes on to crassly denigrate the President. The in-world reason why “Reagan sucks!” happened is that the country’s unions were dying.

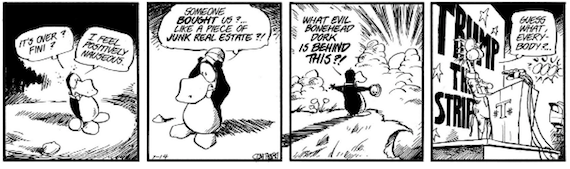

Which brings us (inevitably) to Trump. It’s not just that Bloom County was prescient in seeing his trajectory. Nor is it just that it sussed out the void in his soul. No, what’s so frightening to see now, 30 years after Trump’s turn as Bill the Cat’s brain, is just how precisely it pegged why he shouldn’t have power. The Donald gets into an accident — of a kind that no person would ever survive in real life — and his brain gets transplanted and stuck in his feline host. Without his fortune, business, or wives, Trump has to learn to live humbly, and the strip gives him opportunities to redeem himself which all fail. His final act is to buy out the strip and immediately fire all the characters. The firing supplied Berkeley Breathed with an in-world reason to retire it. Yet what’s notable about this now — beyond how well it captured Trump’s essential robber baron nature — is how it displayed his cruelty in terms of the apocalypse. In its last few weeks in existence, in other words, Bloom County had Trump end the world.

That makes his plot line frankly uncanny these days. But I think it also shows why the strip is worth reading. Although its gags were occasionally silly to a fault, its caricatures made clear why its targets were honestly worrying. In Trump, Bloom County saw a crass, nigh-psychopathic loon, as likely in his way to cause mayhem as a capitalist in Soviet propaganda. When Oliver North went on trial, he showed up in the strip as an alien puppy, whose big, soft eyes and grand rhetoric scuttled his conviction for war crimes. All this metastasizing weirdness bolstered the insight at its core. At heart, Bloom County was not an escape, and that’s why so many felt they needed it.

I can’t think of a better way to spend a weekend than reading it all. Failing that, you can just go on Facebook and start reading the new version for free. As with anything that’s whimsical in the way I’ve laid out, it may strike you as off-puttingly juvenile at first glance. It may seem no different than its fellow classic funnies. But if you keep reading, you’ll come across its takes on devastating scandals, or else its many references to the specter of nuclear war. You’ll see a comic strip that isn’t afraid to show genuine horror at its edges. Based on the number of people who cheered its revival, I think it’s obvious it offered something worth saving.