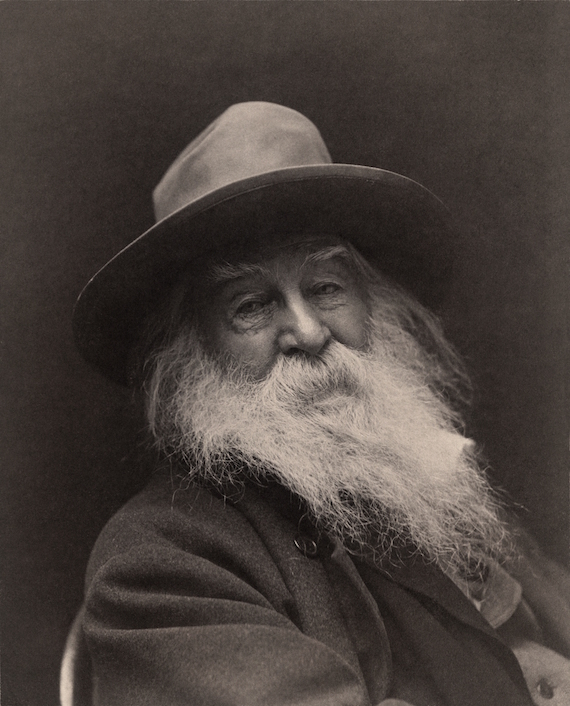

We live in contentious times. In these frenzied days, it’s worth returning to Walt Whitman’s book of Civil War poetry, Drum-Taps. First published in 1865, Drum-Taps reflects on the confrontation of grand visions and the human costs of realizing them. It suggests the importance of empathy in the face of significant ideological disagreement.

The Civil War was in part a great clash of ideas and of visions for what the American republic would be. Abraham Lincoln underlined the stakes of this disagreement in the Gettysburg Address:

The Civil War was in part a great clash of ideas and of visions for what the American republic would be. Abraham Lincoln underlined the stakes of this disagreement in the Gettysburg Address:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.

What the “new birth of freedom” called for in Gettysburg meant might have evolved over time; for instance, the abolition of slavery became increasingly central to the Union’s rhetorical self-defense as the war continued.

But, whatever the evolving notion of the Union, it certainly differed in major ways from how many top Confederates saw secession. In March 1861, in Savannah, Ga., Confederate Vice-President Alexander Hamilton Stephens, a former congressional colleague of Lincoln, outlined his vision for the stakes of the war. Stephens argued that many of those who founded the nation believed that slavery was “in violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically.” According to Stephens, Thomas Jefferson and others believed that slavery would, eventually, end because it violated the principle of equality among men and women. Stephens claimed the Confederacy offered a corrective to this belief in human equality:

Our new Government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition. This, our new Government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.

Stephens found that the “cornerstone” of the Confederacy was the commitment to racial inequality, and this radical philosophical principle justified, in his view, the dissolution of the Union.

Whitman took the side of the Union, the vision of which played a major role in both his poetic and political thinking. In his original preface to Leaves of Grass, Whitman called the United States “essentially the greatest poem,” and the visionary project of a poet for Whitman involved the creation of a broader fellowship that transcended the conventional boundaries of society. He viewed the United States as a vehicle for this enterprise of fellowship.

Whitman took the side of the Union, the vision of which played a major role in both his poetic and political thinking. In his original preface to Leaves of Grass, Whitman called the United States “essentially the greatest poem,” and the visionary project of a poet for Whitman involved the creation of a broader fellowship that transcended the conventional boundaries of society. He viewed the United States as a vehicle for this enterprise of fellowship.

In its record of the Civil War, Drum-Taps homes in on the juxtaposition of vision and the flesh, of aspiration and suffering. For all the great ambition of the antebellum United States, it contained great pain, and the carnage of the Civil War painted in red, white, and gangrene the price of maintaining the hope of the Union. Ideas clashed in the Civil War, but men and women bled. Harvard president Drew Gilpin Faust’s 2008 study This Republic of Suffering argues that the magnitude of suffering and death during the Civil War sent shockwaves through American culture; the equivalent of over 600,000 war deaths in 1861-1865 would be over 6 million deaths in 2016.

The horror of this legacy of pain influenced Whitman’s life and poetry. His brother George served in the Union army throughout the war, and Whitman himself had a front-row-seat for the carnage of the Civil War during his time as a medical orderly. He spent countless hours comforting the wounded and sick soldiers in Washington D.C. and elsewhere. In an 1863 report, he reflected on visiting the wounded at the capital’s Patent Office, which had been converted to a hospital:

A few weeks ago the vast area of the second story of that noblest of Washington buildings, the Patent Office, was crowded close with rows of sick, badly wounded and dying soldiers. They were placed in three very large apartments. I went there several times. It was a strange, solemn and, with all its features of suffering and death, a sort of fascinating sight.

Whitman attended to that magnitude of suffering in Drum-Taps. In one of his notebooks, he claimed that “the expression of American personality through this war is not to be looked for in the great campaign, & the battle-fights. It is to be looked for…in the hospitals, among the wounded.” In many respects, the poems of Drum-Taps are songs for and of the wounded.

One of the most famous poems of the collection, “The Dresser” (later titled “The Wound-Dresser”), narrates the experience of tending to those injured in battle:

Bearing the bandages, water and sponge,

Straight and swift to my wounded I go,

Where they lie on the ground, after the battle brought in;

Where their priceless blood reddens the grass, the ground;

Or to the rows of the hospital tent, or under the roof’d hospital;

To the long rows of cots, up and down, each side, I return;

To each and all, one after another, I draw near — not one do I miss;

An attendant follows, holding a tray — he carries a refuse pail,

Soon to be fill’d with clotted rags and blood, emptied, and fill’d again.

That refuse pail, ever filling and emptying, implies the seemingly endlessness of tending to bodies and spirits ravaged by war. The figures of these soldiers are sacred and exalted — that “priceless blood” — but still they suffer.

Whitman’s verse does not hide that suffering, or the price it exacts:

From the stump of the arm, the amputated hand,

I undo the clotted lint, remove the slough, wash off the matter and blood;

Back on his pillow the soldier bends, with curv’d neck, and side-falling head;

His eyes are closed, his face is pale, he dares not look on the bloody stump,

And has not yet looked on it.

With grim irony, these lines attend to amputations suffered in the name of preserving the Union. Beyond the specific details of this wound-dressing, we see also the signs of the psychological pain of the amputee, who cannot even bear to look at the site of his dismemberment. In “The Dresser” and elsewhere, the poetic speaker does not profess an ability to end this suffering or nullify the pain of the sufferers. Instead, he can only act as a witness to this suffering.

While a book of poetry about war, Drum-Taps offers relatively few presentations of battles. Rather than versifying military maneuvers, Whitman offers a broader catalogue of perspectives — of mourning parents, thriving cities, moonlit nights, and ford crossings. This catalogue presents the greater context within which the violence of the war occurs.

Short poems — like sudden perspectival knives — cut in between many of the longer poems of Drum-Taps. Some of these poems might not even seem to be about the war at first:

Solid, ironical, rolling orb!

Master of all, and matter of fact! — at last I accept your terms;

Bringing to practical, vulgar tests, of all my ideal dreams,

And of me, as lover and hero.

But this sudden flourish of reflection has clear connections to the war. The ideal dreams and fancies of Whitman and his fellow Americans have become subject to the hard trials of gunpowder, bayonet, and surgeon’s saw. And these tests of dreams pierce human hearts.

Some of Whitman’s early poems about the Civil War at times adopt a triumphalist, celebratory mode. Written in 1861, “Beat! Beat! Drums!” conjures the explosive excitement of the coming war. The poem opens with the exhortations “Beat! beat! drums! — Blow! bugles! blow! / Through the windows — through doors — burst like a force of ruthless men.” With the force of blaring trumpets, tidings of war come to disrupt the conventional comforts of civilian life in peace.

We risk simplifying this poem, however, if we view it only as a gilded celebration of war. The diction of the final stanza, for example, suggests an undercurrent of horror in the thrill of the pounding drums.

Beat! beat! drums! — Blow! bugles! blow!

Make no parley — stop for no expostulation;

Mind not the timid — mind not the weeper or prayer;

Mind not the old man beseeching the young man;

Let not the child’s voice be heard, nor the mother’s entreaties;

Make even the trestles to shake the dead, where they lie awaiting the hearses,

So strong you thump, O terrible drums — so loud you bugles blow.

The drums and bugles have no time for argument or sorrow or prayer. They break up families — splintering old from young, parents from children — and seem a prelude to a multitude of bodies, which lie awaiting hearses to bear them away.

Near the end of the book, especially with the “sequel” tacked on like a mournful suffix in October 1865, Whitman reflected in depth on the devastation of the war. After the electric pounding of the visionary drums, the verse surveys a battlefield littered with broken bodies, severed limbs, and pale corpses. Abraham Lincoln — especially in a poem such as “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d” — becomes a representative figure: an emblem of the Union’s cost. Whitman, though, did not stop with Lincoln. Many of the poems of Drum-Taps reflect on the suffering of the simultaneously anonymous (because unnamed) and personalized (because shown as people with essential dignity) soldiers. In part through this assertion of common suffering, Drum-Taps aims to unite a divided nation.

“Reconcilitation,” the penultimate poem of the original 1865 version of Drum-Taps, offers a meeting of North and South, of living and dead:

Word over all, beautiful as the sky!

Beautiful that war, and all its deeds of carnage, must in time be utterly lost;

That the hands of the sisters Death and Night, incessantly softly wash again, and

ever again, this soil’d world:

…For my enemy is dead — a man divine as myself is dead;

I look where he lies, white-faced and still, in the coffin — I draw near;

I bend down and touch lightly with my lips the white face in the coffin.

In this moment, Whitman’s verse presents a scene of recognition of an essential humanity across radical differences: that enemy is “a man divine as myself.” Whatever the differences of cause between these two men — and these differences may yawn chasm-wide — they have a common human fellowship.

Rather than succumbing to self-righteous demonization, Whitman illustrated the power of a human empathy that transcends ideological bellicosity. This empathy does not ultimately nullify ideological difference — Drum-Taps does not call for the defeat of the Union in order to end the war — but empathy does situate this difference in a more complicated context.

There were huge differences between the visions of the Union and the Confederacy, but those differences did not nullify the fact that partisans of both sides were human beings, with the inherent worth shared by all men and women. Though he opposed the Confederacy, Whitman also sought to show the dignity of the Confederate soldiers not because he believed in their cause but because they were human beings. In his time nursing wounded soldiers, Whitman cared for both Union and Confederate men. He wrote, for instance, of watching over a Confederate prisoner of war whose leg was amputated. Whitman’s empathy as both an artist and a man was not only a gift for those with whom he agreed or whose cause he applauded. Whitman’s project in Drum-Taps reminds us of the way that poetry (and literature in general) can strive to keep us alert to our deeper bonds.

Whitman’s poetry chose the harder path of empathy. In its portrayal of human suffering, Drum-Taps notes the price exacted by grand — even noble — visions in this “soil’d world.” The collection suggests the importance of leavening a thirsty idealism with an essential human respect.

Previously: “Embracing The Other I Am; or, How Walt Whitman Saved My Life”

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.