1.

Hookup culture is destroying relationships and intimacy, Nancy Jo Sales declared in a 2015 Vanity Fair article. She quoted everyone from banking bros who bragged about their numbers of Tinder conquests, to social scientists who believe hookup culture is as revolutionary as the introduction of marriage 10,000 years ago. But what if you aren’t hooking up? Where do you fit in?

Emma Rathbone asks these questions in her second novel, Losing It. Her protagonist, Julia Greenfield, is a directionless 26-year-old fixated on the fact that she’s still a virgin. Not for lack of interest, but misplaced optimism — she declines a high school boyfriend’s request to have sex in a pool, assuming she could “afford to decline, if only to make the next proposition all the more delicious.” Except the next proposition never comes, and as the years pass Julia’s fear of having to tell men she’s a virgin consumes her and ruins any chance she has of sex. When her parents suggest she spend the summer with her maiden aunt Vivienne in Durham, North Carolina, Julia decides this will be her opportunity to lose “it.” A new girl in town during a hot North Carolina summer seems like the perfect scenario, but awkward Julia self-sabotages: taking a boring office job where everyone is old and married; going on online dates with misogynists; and learning that Vivienne is a 58-year-old virgin, Julia’s own worst nightmare. As she writes, “That was the problem — to want something so badly was to jam yourself into the wrong places, gum up the works, send clanging vibrations into the cosmos. But how can you step back and affect nonchalance?”

We’re supposed to be rooting for Julia, but just as Julia concludes that there is something “too much” about Vivienne’s personality that prevented her from pairing up, there is something likewise lacking in Julia’s that keeps her single. She picks bad lovers, says the wrong thing, and completely misjudges any romantic moment to tragicomic effect. It’s a testament to Rathbone’s writing that we still find Julia sympathetic even as it becomes clearer that Julia’s own poor decision-making is part of the issue. She is an anti-hero of her own story, solely because of a fluke of sexual chemistry and opportunity. As a middle-class, well-educated, heterosexual white woman, Julia should’ve had dozens of opportunities to have sex, but she is a statistical anomaly, who doesn’t quite fit in with the hook-up generation of her peers, or with the self-declared spinster Gen-Xers before her.

2.

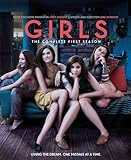

If there is a poster girl for sex-positive millennials, it’s Lena Dunham. In the 2012 pilot of her HBO show Girls, we see Dunham’s character engaged in bad couch sex with her not-quite boyfriend. This was her sexually liberated battle cry, that millennial women were hooking up and not ashamed of it. Dunham’s own writings have followed suit, with much of her essay collection, Not that Kind of Girl, devoted to her own sexual experiences in college and beyond. In “Take My Virginity (No, Really, Take It),” Dunham writes about being “the oldest virgin in town” (with “town” being Oberlin college) as a college sophomore; already, virginity is a burden that must jettisoned to fit in with the anything-goes sexuality of her liberal arts school and her later career.

If there is a poster girl for sex-positive millennials, it’s Lena Dunham. In the 2012 pilot of her HBO show Girls, we see Dunham’s character engaged in bad couch sex with her not-quite boyfriend. This was her sexually liberated battle cry, that millennial women were hooking up and not ashamed of it. Dunham’s own writings have followed suit, with much of her essay collection, Not that Kind of Girl, devoted to her own sexual experiences in college and beyond. In “Take My Virginity (No, Really, Take It),” Dunham writes about being “the oldest virgin in town” (with “town” being Oberlin college) as a college sophomore; already, virginity is a burden that must jettisoned to fit in with the anything-goes sexuality of her liberal arts school and her later career.

This freewheeling upper-middle-class millennial archetype appears frequently in fiction, too. Adelle Waldman explores the male perspective in The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P (a book Dunham also praised), in which the titular protagonist sleeps with his intellectual circle as a distraction from the book he’s writing. Sex is presented as an afterthought, though clearly it seeps into all aspects of life, even as everyone pretends not to care. The challenge of so-called laissez-faire sex is the main theme running through Katherine Heiny’s short story collection, Single, Carefree, Mellow. The characters are anything but what the title suggests, spending most of the stories conflicted about their supposedly casual affairs. In these books, it’s never a question of will they or won’t they, but whether it will mean anything after they do. The very impetus of the story is sex, hence there are no stories for the sex-less, intentional or not.

This freewheeling upper-middle-class millennial archetype appears frequently in fiction, too. Adelle Waldman explores the male perspective in The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P (a book Dunham also praised), in which the titular protagonist sleeps with his intellectual circle as a distraction from the book he’s writing. Sex is presented as an afterthought, though clearly it seeps into all aspects of life, even as everyone pretends not to care. The challenge of so-called laissez-faire sex is the main theme running through Katherine Heiny’s short story collection, Single, Carefree, Mellow. The characters are anything but what the title suggests, spending most of the stories conflicted about their supposedly casual affairs. In these books, it’s never a question of will they or won’t they, but whether it will mean anything after they do. The very impetus of the story is sex, hence there are no stories for the sex-less, intentional or not.

The generation ahead of the millennials has reclaimed singledom as a social movement. Kate Bolick’s memoir/history book Spinster is about redefining the formerly pejorative word. To Bolick and the women she profiles — among them Edith Wharton and Neith Boyce — spinsterhood isn’t about virginity or chastity, but rather about proudly living as an unmarried, and thus unemcumbered, woman. She concludes that “spinster” is a dated concept: “The choice between being married versus being single doesn’t even belong here in the twenty-first century.” Rebecca Traister develops the thesis further in All the Single Ladies, her nonfiction examination of just what it means socially and politically when women have more choices than just marriage. The first single women spawned revolutionary movements from abolition to suffrage, and with only 20 percent of Americans married by age 29 today, single women could continue to change the dominant culture. “Single women are taking up space in a world that was not built for them. We are a new republic, with a new category of citizen,” she writes. Being single is a call to action in these books, but it’s also a choice.

The generation ahead of the millennials has reclaimed singledom as a social movement. Kate Bolick’s memoir/history book Spinster is about redefining the formerly pejorative word. To Bolick and the women she profiles — among them Edith Wharton and Neith Boyce — spinsterhood isn’t about virginity or chastity, but rather about proudly living as an unmarried, and thus unemcumbered, woman. She concludes that “spinster” is a dated concept: “The choice between being married versus being single doesn’t even belong here in the twenty-first century.” Rebecca Traister develops the thesis further in All the Single Ladies, her nonfiction examination of just what it means socially and politically when women have more choices than just marriage. The first single women spawned revolutionary movements from abolition to suffrage, and with only 20 percent of Americans married by age 29 today, single women could continue to change the dominant culture. “Single women are taking up space in a world that was not built for them. We are a new republic, with a new category of citizen,” she writes. Being single is a call to action in these books, but it’s also a choice.

Of course, this new singledom can come with unexpected hitches. “In a culture that has more fully acknowledged female sexuality as a reality, it is perhaps more difficult than ever to be an adult woman who does not have sex,” Traister writes. She continues to tell the story of sexually willing women who couldn’t find the opportunity to have sex, including herself (Traister didn’t lose her virginity until age 24), describing it with increasingly negative vocabulary: freighted, loom, frigid, cumbersome. Virginity is pathologized after a certain age.

3.

While millennials and Gen-Xers ultimately have different views on singledom and sex, both are fighting against a previous narrative that dictated social mores (particularly for women). But someone like Rathbone’s Julia Greenfield was never part of the narrative to begin with. This doesn’t leave her much room in literature or even culture. Indeed, literary virgins with any agency are few and far between.

The most infamous example is Charles Dickens’s Miss Havisham in Great Expectations. After being left at the altar, she retreats to a mansion, where she never takes off her wedding dress and is described as a witch. She is a pitiful wreck whose forced virginity pushes her to mental breakdown and full removal from society. Even Jeffrey Eugenides’s titular virgins in The Virgin Suicides are more figurative than literal virgins. They are trapped by both their strict parents and the narrative the neighborhood teenage boys impose on them, effectively fetishizing their virginity. All of these women’s fates are decided and described by men, both by the domineering men who keep them virgins and the male authors who write about them. They are modern-day cautionary tales.

The most infamous example is Charles Dickens’s Miss Havisham in Great Expectations. After being left at the altar, she retreats to a mansion, where she never takes off her wedding dress and is described as a witch. She is a pitiful wreck whose forced virginity pushes her to mental breakdown and full removal from society. Even Jeffrey Eugenides’s titular virgins in The Virgin Suicides are more figurative than literal virgins. They are trapped by both their strict parents and the narrative the neighborhood teenage boys impose on them, effectively fetishizing their virginity. All of these women’s fates are decided and described by men, both by the domineering men who keep them virgins and the male authors who write about them. They are modern-day cautionary tales.

This is what makes Losing It subversive. We understand Julia’s hesitation, which is almost radical in this world of swipe-happy 20-somethings. But even though her characters may be ashamed of their virginity, Rathbone isn’t ashamed on their behalf, and so gives voice to a silent subgroup. This isn’t just Julia’s story; it’s also Vivienne’s, and Rathbone decides not to give us a definitive reason for why Vivienne is still a virgin. There are no Miss Havishams here. Sometimes nothing is wrong; sometimes it just doesn’t happen. (And sometimes, in Julia’s case, it does.)