For my friend’s birthday last month, I gave her a tiny zine, three-by-three inches of simply drawn fruits in the bold, limited-color palette of a children’s book. The fruits have sweet, anthropomorphized faces with details added to the pages by hand post-printing, like the glitter gel pen outline of a banana’s half-opened peel (inside, the banana blushes). The orange peers knowingly over its shoulder, showing off a perfectly placed navel-butthole. The carrots, eyes closed, suck each other’s ends. Grapes, in a cluster, fuck.

“Does this artist make these as posters?” my friend asked. “I want these on my kitchen wall.”

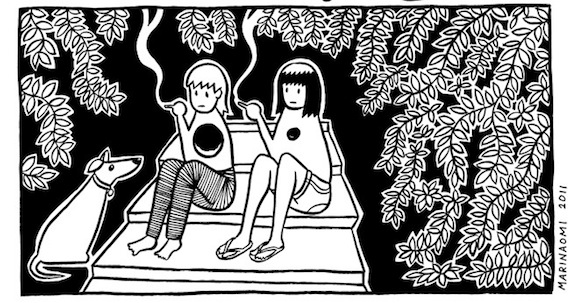

That was her introduction to MariNaomi, and it’s not a bad one. Though the minicomic, Dirty Produce, is a departure from the cartoonist’s work in its major points — in full color, wordless, not autobiographical — it gives a glimpse of her signature minimalist design, her sexual frankness, and her joyfully dirty sense of humor.

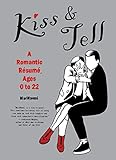

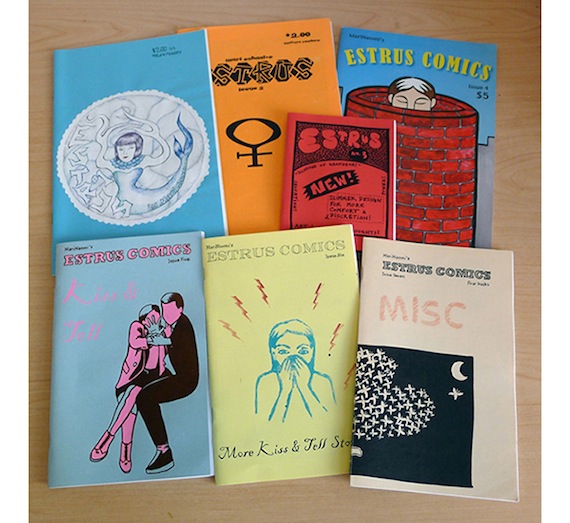

MariNaomi published her first graphic memoir, Kiss & Tell: A Romantic Résumé, Ages 0 to 22, in 2011. Her second book, Dragon’s Breath and Other True Stories (2014), is darker — she jokingly calls it her “book of dead friends” — mostly made up of short stories she published on The Rumpus. It was nominated for an Eisner Award. She also runs the Cartoonists of Color Database and the Queer Cartoonists Database.

MariNaomi published her first graphic memoir, Kiss & Tell: A Romantic Résumé, Ages 0 to 22, in 2011. Her second book, Dragon’s Breath and Other True Stories (2014), is darker — she jokingly calls it her “book of dead friends” — mostly made up of short stories she published on The Rumpus. It was nominated for an Eisner Award. She also runs the Cartoonists of Color Database and the Queer Cartoonists Database.

Her new book, Turning Japanese, picks up not long after Kiss & Tell ends. Mari, in her early-20s, has just gotten out of one serious relationship and into another when she hears of an opportunity to work at a Japanese hostess bar in San Jose. This job soon leads her to another hostess bar, in Japan this time, where she decides to move for a few months with her fiancé, eager to get to know her mother’s home country as an adult.

I talked to Mari over tea at her house in Los Angeles as her two dogs and four cats slept nearby.

TM: In your memoir work, you’re talking so openly and honestly about things that happened to you, but at the same time, I don’t get the sense that it’s confessional or that I’m reading more than you want to show to the reader. How do you find that balance between the stress of reading through and processing all of those difficult experiences and then getting it onto the paper as this compact, confidently told story?

MN: One of the things that people say to me the most after they read my stuff is, “Oh, you’re so honest,” or “You’re so open,” and it’s so funny because pretty much every graphic memoirist I’ve talked to, we all hear that from people, but every single one of us is like, we’re only showing you what we want you to see. There are so many things left out.

TM: Do you feel your relationships have changed now that you publish memoir? Are people more afraid of offending you?

MN: You know, when I started writing Kiss & Tell, which was before I met my boyfriend who would eventually be my husband, I remember hooking up with some guy, and at some point I told him about my project and he was like, “Say goodbye to dating.” Oh, great. People like to ask my husband how he feels about those things, but actually he read my comics, and that was what interested him in me. He liked the honesty. “Honesty” in quotes. The only times there have ever been, I wouldn’t even say issues, are when I want to tell something about our private life, and I’m like, could I write about this? He’s like, no, maybe not. He usually gives in eventually.

TM: Is he a reader for you when you’re in your early stages?

MN: Oh yeah. He’s my muse. Every time I make a comic, I’m either trying to make him laugh or cry, and if he reads it and then hands it back to me and says, “This is good,” I know I’ve failed. I usually get all like, “What do you mean it’s good?!”

TM: I was reading about your parents’ response to Kiss & Tell, that your dad took his time to read through it and your mom just read a little and put it aside for a while.

MN: Forever.

TM: Forever! She never read the whole thing?

MN: I hope not, no, I don’t think so. I spent the whole time between when I got the book deal and when the book came out convincing her not to read the book. She’s only kissed my dad, I mean —

TM: It’s a totally different experience.

MN: Yeah. And she’s never done drugs, or — she’s just coming from such a different place. And she’s my mom. So I would tell her these really horrible parts of the stories to distract her because she’s also very curious, and I knew that at some point she wouldn’t be able to resist. So one of the first things I told her was, “I wrote about my first blowjob. The guy didn’t wash himself, Mom. Do you really want to read that? I drew flies around his penis, Mom. Do you really want to read that?” And she’s like, “No, no, I’m never reading it.” I even tested them out a little, thinking maybe I’d show them a couple of comics and see if they could handle it. There’s a story about when I mooned a little kid, and my mom read that and she said, [gasp!], and I said, “Okay, that’s it! If that shocks you, we’re done.”

TM: When do you decide to hide a person’s identity? Is it when they explicitly say please do this, or does it depend on your relationship?

MN: No one has said that. I guess I opt to hide their identity more than I opt not to. It seems like a good rule of thumb. I mean, I’ve been doing this since the ’90s, and I’ve gone through a lot of trial and error, and I’ve pissed off a couple of people. I can only just try to get better and not hurt people, but I also need to tell my story.

TM: Some people are more sensitive than others, I guess, about those things.

MN: Yeah. And it’s so funny too, when I was doing Kiss & Tell, I didn’t tell everybody who was in it, and there are a couple people, like the dingleberry guy, who I thought, “Am I going to get an angry email from him sometime?” But there are a couple people whose stories I thought were really benign and just kind of cute and when I showed them the stories, one guy in particular was like, “Oh my god, I’m so sad and horrified by how I treated you.” I’m like, “What? It was all consensual.” But you never know.

I did this other comic that didn’t end up in Kiss & Tell because it happened later than age 22, where I went on a couple dates with this prison warden, and I paid more attention to her dog than I did to her. When I showed the comic to her years later, I thought she might be mad, but she loved it. So you just never know. People react differently and you can’t control it. All I can do now is try to avoid getting in trouble.

TM: When did you start keeping journals?

MN: My first one was bought for me right when I moved to the San Francisco Bay Area when I was seven, turning eight. It was my eighth birthday, and I wrote about wanting to have sex with Michael Jackson, at eight years old, which actually was probably my only chance, right? But I was so scandalized that I was having these thoughts that I had to write the word upside down and backwards so that my parents wouldn’t figure it out, the word s-e-x. I think they would have figured it out.

My childhood journals are creepy. I would fly into rages about things. When I’m reading myself as a kid, I think, ugh, maybe that’s why I don’t like kids, because I didn’t like myself as a kid. What a little brat I was.

TM: You’re going back and reading your old journals closely for your new project. Have you been doing that with every project?

MN: Well, this is the first time actually that I’ve gone through the agendas, the schedules, the calendars…They’re so fucking boring, holy crap. The journals are more about feelings, so they’re not painting a very accurate portrayal of what’s going on in my life. For some reason, I felt — and I don’t do this anymore, but I felt that I had to compulsively write down everything: what I ate, but not for any reasons, and it’s not every day, it’s not consistent. Some days it would be, “We went to Mill Valley Market before work, picked up a sandwich, turkey and avocado, and a Pepsi, and in brackets, [bottle].”

TM: So meticulous.

MN: This book was originally going to be about an ex-friend, but I think it’s really going to be about memory.

TM: Do you feel obligated or responsible to be totally truthful?

MN: I feel like responsibility in art is kind of a loaded concept because there’s never any point when I’m creating where I stop myself from saying something. If I did that, I would just stop making art and writing entirely. Because there’s really no way to not offend anybody. Someone’s always going to get offended, no matter what. They’re all bringing their own shit to the table. And the artist’s job really is to tell the story that you want to tell with as little confusion as possible.

Every once in a while, like for Turning Japanese, there are a couple things that, way after the fact, I looked at and thought were kind of offensive and didn’t come out the way I intended, so I took them out. It’s not censorship, exactly, it’s just clarifying.

I wish I could stop time and redraw all my books. Like all the comics that I’ve ever done. But then by the time I’d be done with them, I’d just want to start over again because I’d be that much better. Can’t win.

TM: Isn’t it kind of nice, though, to see how much you’ve changed over time, or how much your technique has changed?

MN: No, I wish I were perfect before. There are certain things that I used to do, like it used to take me so long to do a comic because I was all about stippling and crosshatching, and it just took forever. Sometimes I bother with that stuff now if it’s important, but I guess I read a lot of Robert Crumb, and I was like, I just want to see a million crosshatches!

TM: What are some of the other comics that have influenced you most?

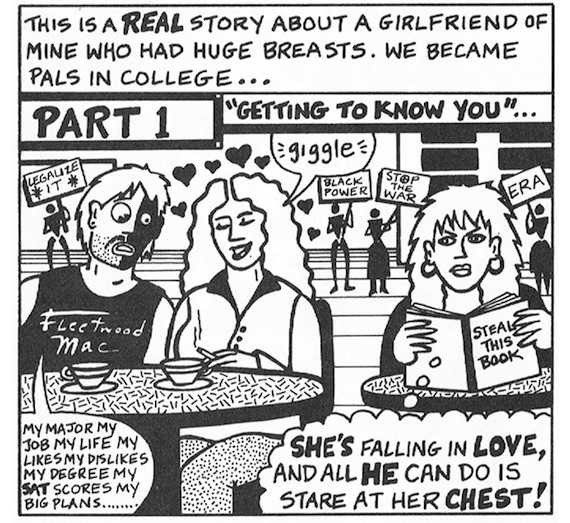

MN: I was motivated to make comics from a specific comic that I read in the anthology Twisted Sisters: A Collection of Bad Girl Art called “The Jelly” by Mary Fleener. That was the definitive point where I went from a reader to a maker. I read it and thought, this is brilliant, and I have stories like this too — I could do this. Here, I’ll show you.

MN: I was motivated to make comics from a specific comic that I read in the anthology Twisted Sisters: A Collection of Bad Girl Art called “The Jelly” by Mary Fleener. That was the definitive point where I went from a reader to a maker. I read it and thought, this is brilliant, and I have stories like this too — I could do this. Here, I’ll show you.

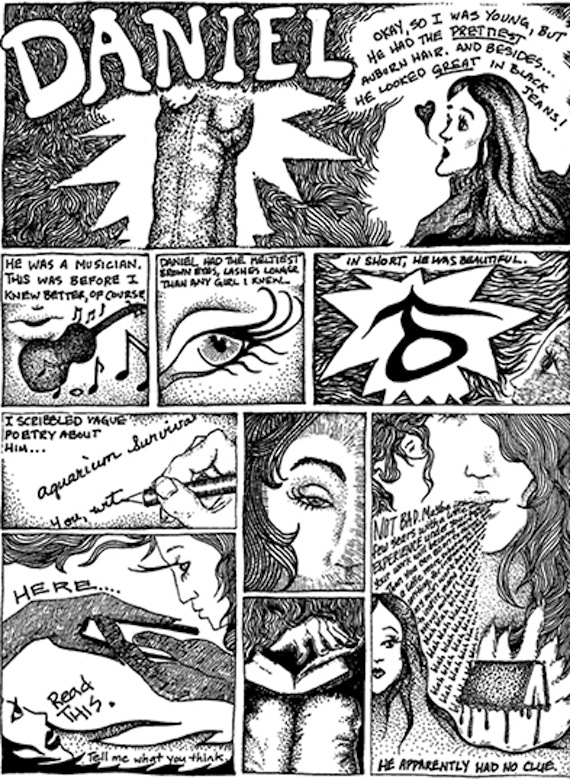

MN: Here it is. So this is her comic. It was about this horrible roommate she had, and I was like, I’ve had horrible roommates, and this is so funny. I love her stuff. It’s so trippy and hilarious and so when I started making comics, this was the first comic I ever made.

TM: When did you make that one?

MN: March 1997?

TM: It’s so different from your current style.

MN: Yeah, it’s so different. But it took forever. I mean, just look at all of those little lines.

TM: What’s something recent that you read and really liked?

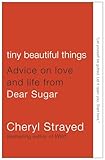

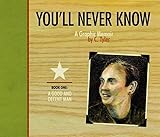

MN: So many things! I could give you a list of 100. One that just got re-released is Carol Tyler’s trilogy, You’ll Never Know. It’s a memoir slash biography of her father, who is a vet, and it’s about his PTSD. Another thing that I really love, and this isn’t tainted by the fact that she’s one of my closest friends, is Yumi Sakugawa. She came out with a zine called Never Forgets that, oh my god, just made me cry. It’s one of my favorite things I’ve read in comic form. A non-comics influence would be Cheryl Strayed. Her advice column that got collected into Tiny, Beautiful Things had a huge impact on me.

MN: So many things! I could give you a list of 100. One that just got re-released is Carol Tyler’s trilogy, You’ll Never Know. It’s a memoir slash biography of her father, who is a vet, and it’s about his PTSD. Another thing that I really love, and this isn’t tainted by the fact that she’s one of my closest friends, is Yumi Sakugawa. She came out with a zine called Never Forgets that, oh my god, just made me cry. It’s one of my favorite things I’ve read in comic form. A non-comics influence would be Cheryl Strayed. Her advice column that got collected into Tiny, Beautiful Things had a huge impact on me.

TM: In Turning Japanese, you’re living in Japan for the first time and learning how to communicate. What is it like for you being in Japan? Do people usually assume that you’re Japanese?

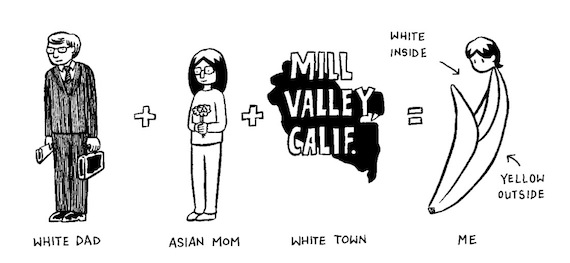

MN: No. I don’t look Japanese to them. When I was doing hostessing there, I was blonde, and no one believed I was part Japanese at all. I would tell them I was half, and they wouldn’t believe me. They always thought I was Spanish or Russian when I was hostessing. When I was working in the San Jose bar, the Japanese visitors or expats, they wouldn’t think that I was Japanese at all either. So, never fit in anywhere [Laughs].

TM: Gives us a good vantage point, though.

MN: I was never big on fitting in, it’s fine. I stopped caring about fitting in at like 8th or 9th grade, but in 6th and 7th grade for some reason, I just really wanted people to think I was cool, which — I was so not cool. There’s a picture of me that I looked at a couple years later and was like, “Oh, that’s why nobody liked me.” I’m going up some staircase and the teacher took a picture of me, and I’ve got super long hair that’s not combed, it’s so all over the place, it’s a middle part, and I’m wearing Sanrio everything. The biggest nerd. I’m wearing hot pink capris and a little sailor thing that goes with it. I mean, this was 6th grade — people were wearing designer jeans and making out. It was a Little Twin Stars set, and then I had a Tuxedo Sam backpack and Tuxedo Sam velcro shoes and a Tuxedo Sam whistle hanging from my neck. I wanted to beat me up, looking at that picture. Wow. I also want to beat me up and steal my Tuxedo Sam backpack because that thing’s awesome. He was my favorite.

TM: You were born in Texas, right? What part of the state did you live in?

MN: Near the panhandle.

TM: I used to live near Dallas, in middle school and high school.

MN: What was the Asian situation there?

TM: I had this friend who was Chinese-American from New York, and we became really close friends and we would watch Bruce Lee movies together. But I remember one day she was going through the yearbook and finding all the Asian people because there weren’t that many, and she was like, “Oh, there’s Julie. She doesn’t count because she was adopted.”

MN: Oh my gosh.

TM: And I was like, wow, what do you think about me then? And our friendship just kind of started to dissolve. But yeah, there weren’t many other Asians around. Was race or being Japanese something you talked about with your mom or your siblings?

MN: No, I don’t think I ever talked about it with them. The first time that I ever really remember talking about race with anyone was with a guy I met who was my first Asian friend, and he was also my first zine friend, and we would talk about, I guess, our moms. But I don’t know, he’s a guy. We would mostly talk about food. I was just so grateful to have someone to talk about that stuff with, I mean, all these things I noticed but had not been able to put to words, certain Japanese customs, certain kinds of passive aggressiveness in the culture, and xenophobia that I had noticed, but I was like, I don’t know, am I just imagining that? There were so many things that I thought were just my mom being quirky, but then I realized later that, oh no, this is a cultural thing. This is completely normal elsewhere.

There was one quarter Japanese—Quapa—guy who went to my middle school for like a year, but he and I avoided each other. And then there was one girl who was Japanese, her parents owned the Japanese restaurant, and we also avoided each other. It was interesting. I mean, already, I guess I felt like I didn’t fit in, so to — I don’t know, maybe not.

TM: It’s very complicated.

MN: Yeah, especially that age.

TM: Has your parents’ relationship with your work changed or are they still nervous about reading it?

MN: Well no, they were happy that my second book (Dragon’s Breath and Other True Stories) was something that they could read, so that was good. The nicest things that my mom has ever told me in my life were about that book. I archive everything in my Gmail, but that’s the one email that I keep out because it’s like, oh, Mom. She doesn’t pay a lot of compliments, so it was really sweet.

Images courtesy of MariNaomi and Mary Fleener