Daniel Harris begins “The Sacred Androgen,” his Antioch Review essay on “the transgender debate,” with a dutiful recounting of the travails transgender people face today: violence inflicted by others and self, bullying, lack of access to resources, etc. Harris does not condone these trials. He goes on to assure his readers that whatever decisions we transgender people make about ourselves, he still believes in our “humanity.”

By the end of the essay, Harris’s readers would be forgiven for doubting this assertion. “The Sacred Androgen” is a mess of unreflective bigotry, incoherent assumptions, and wildly inaccurate conclusions. Harris uses outmoded, offensive, or simply strange terminology, referring to transgender people as “TGs,” trans women as transitioning “from virago to vamp,” or as “Mrs. Doubtfires or Victor Victorias.” Harris’s research methods date him as much as his movie references; most of his anecdata seem to have been collected from AOL chat rooms for macho “studs” and the trans women they fetishize. In the light of this content and the alternately patronizing and hostile tone of the essay, Harris’s opening paragraph reads like an attempt at inoculating himself against the inevitable criticism of what follows.

Not surprisingly, the essay has been widely decried. In Medium, Gabrielle Bellot writes that, “pieces like this…crassly marginalise and attack vulnerable communities.” Brynn Tannehill on the Huffpost Queer Voices blog writes that her time living near Antioch College “as an out transgender person was a lonely, soul-crushing hell,” an experience Harris’s essay confirms. A petition denouncing the Antioch Review for publishing the essay has collected more than 4,000 signatures.

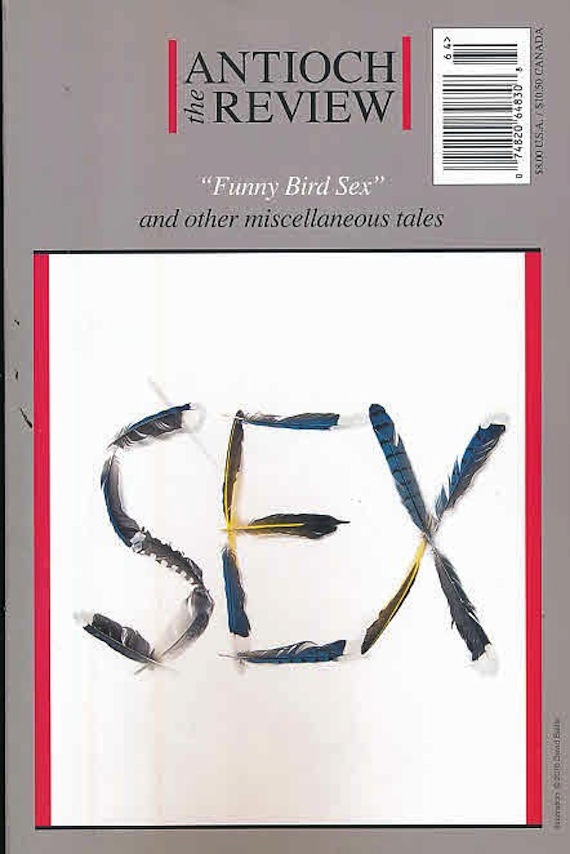

The Antioch Review, for its part, first punted to Antioch College itself, which issued a typically milquetoast appeal to “free expression.” On realizing the fervor wasn’t going to die down, Antioch Review editor Robert Fogarty wrote that, “I sincerely regret any pain and hurt that the publishing of this piece has caused,” promising to publish responses in future issues. One almost feels sorry for Robert Fogarty, who has been the journal’s editor since 1977, when you didn’t have to worry about transgender people. The Antioch Review has the reputation of being prestigious yet staid (an account of the magazine’s history on their website makes their 2013 transition to digital JSTOR archives sound like a giant leap for mankind). This controversy may bolster their readership, though more likely it will act as a cautionary tale for what happens when a stagnant editorial staff leaves a magazine out of touch.

“The Sacred Androgen,” while purporting to say what good liberals won’t, actually operates like a juvenile game of “gotcha.” Harris seems to believe that if he can expose enough supposed inconsistencies in how we trans people talk about ourselves, the house of cards we’ve constructed will fall apart altogether. To that end he accuses transgender people of being subject to a “mass delusion,” the fault lines of which emerge in our discussions of the differences between transgender and transracial identity, the way we talk about fetishes and sexual pleasure, and in our claims to radical embodiment vs. how radical we actually are, to name a few.

Each of these gotcha moments requires the creation of a straw man — typically a straw trans woman, in this case — who espouses views Harris believes to be hypocritical. Transgender people have long been distancing ourselves from the “trapped in the wrong body” narrative (itself a simplified creation for the benefit of mainstream media), to name just one example, yet Harris takes for granted that we all believe this about ourselves. Because Harris doesn’t source any of his straw people, we don’t know who believes that, for example, “a fetish [is] not a legitimate reason for modifying one’s body.” No doubt some trans people do; yet to assume a monolithic set of beliefs is to radically ignore the nuances in the last decade-plus of conversations on transgender identity.

This is not to say that there are no inconsistencies in the ways in which we trans people talk about ourselves, or that there is no room for exploration or growth. Like a toddler sensing a word is “bad” without knowing why, Harris shows a remarkable ability to hone in on the issues that get trans people feeling defensive. Take the Rachel Dolezal controversy, which he brings up with glee: Trans people have yet to come up with a foolproof answer to the question of whether transgender can equate to transracial. This is because the issue, like all questions involving the thorny intersections of identities, is complicated.

But here’s the thing: What’s the reason trans people rush to defend the legitimacy of our identities at the first challenge, often at the cost of complexity or rational discussion? It’s because of assholes like Daniel Harris, who prey on the burden of proof transgender people feel we need to justify our existence. As if our lives require the armor of pristine argumentation; as if every inconsistency makes us less real. If this were the case, this article should have made Harris himself disappear into the ether.

Unfortunately for his argument, Harris is unable to distinguish the gotcha points that are worth pursuing from the ones that are patently ridiculous. Among the latter includes the suggestion that trans women are failed homosexual men. Not only is this offensive, it doesn’t make sense: many trans women are attracted to other women — how do they fit into the paradigm of the “homosexual manqué?” Not to mention the many trans women that don’t want to “achieve an hourglass figure with gigantic breast implants,” a demographic that — like trans men — Harris doesn’t seem to realize exists. So it’s difficult to take the potentially productive provocations — such as the equation between transgender rhetoric and positive psychology — seriously. How can we be expected to, within a framework that says we must be intellectually incontrovertible in order to exist?

The real question is why Harris felt the need to write this. His tone suggests his resentments have been building for some time, but why? His familiarity with transgender people in the post-AOL world seems to be limited to knowing the names of Caitlyn Jenner and Laverne Cox. I doubt he knows many transgender people personally (and I feel pretty sorry for the ones he does), nor do I suspect transgender people are constantly demanding onerous accommodations from him. The younger, campus-based faction of the transgender community could have provided Harris with enough material for a mean-spirited mockery (Making up YOUR OWN pronouns? What next?!?), but he doesn’t know enough about transgender culture to be able to take advantage.

There are really two questions. Why does Harris claim — explicitly or implicitly — that he wanted to write this, and why did he really want to write this? Both questions interest me. Both deserve to be discussed, because the sad truth is that Harris’s feelings aren’t uncommon. Because of my various privileges — my masculinity, my whiteness, my socio-economic mobility — I don’t typically encounter animosity like Harris’s. But I hear enough of these views secondhand all the time: in the comment sections of articles, in the accounts trans women give of trying to go about their dating lives or simply daily lives, in the subtext of news reports on hate crimes. Harris’s essay feels like an unburdening, the kind of cut-the-PC-crap that’s popular with — dare I say it — the Donald Trump crowd. For all of its pretense at provocation, the essay is often no more than a dressed-up version of a bro on a dating app who messages a trans woman to say, “You can say you are who you say you are, but know that I’ll never see you that way.”

“The Sacred Androgen” cloaks malice in the language of concern. Daniel Harris doesn’t want trans people to fail. He wants them to realize that taking hormones won’t solve their problems, that they could be left “as out of sorts with their bodies and their failure to pass as they were before they underwent hormone replacement therapy.” All that trouble, and we still won’t look real. Trans women would do better to come to terms with their limits: “men’s noses are too big, shoulders too broad, jaws too square, voices too deep, brows too beetling, and gait — at least in heels — too lumbering” to effect any convincing change.

Plus, he’s concerned about the children. Under the sway of the trans-brainwashed media, well-intentioned parents may make an “irreversible decision” in giving their child “hormone therapy.” It’s yet another of the essay’s many inaccuracies: children do not receive hormone therapy in the sense of injecting estrogen or testosterone, they receive hormone blockers that buy them time to make their own decisions. But who cares about factual rigor when you’re playing the oldest trick in the book: mobilizing “innocent” children for culturally conservative ends?

If Harris’s rationale for writing the essay really was concern for the self-esteem of transgender people or the futures of children, we could dismiss his arguments as misguided or patronizing. But I know Harris didn’t write his essay out of concern. As much as he’d like us to believe it, he didn’t write the article to open up a conversation he perceives as stifling, either. Let’s look a little closer to find the real reason.

It starts with his thoughts on plastic surgery. Harris purports to appeal to a shared ethos when he claims that “the general public almost universally disapproves of plastic surgery.” His source for that wildly sweeping generalization we’ll never know, but what are sources, really, in the face of the ridiculous things that women do? Listen to the pleasure Harris takes in describing the “botched” plastic surgeries of celebrity women: “The obscene trout pout of Donatella Versace, the misshapen nipples and oblong breasts of Tara Reid, the Joker’s grimace of Kim Novak.”

Ah yes, it’s always fun when women fail. How harmless, to peruse the clickbait of plastic surgeries “gone wrong” and laugh at the litany of misguided attempts to secure the male gaze. Because these women are silly, aren’t they? Their breasts, their ambitions: they are all too much. Cisgender women often undergo plastic surgeries because they want to be women in excess. This hostility towards excessive femininity underlies Harris’s criticism of trans women: “Their mimicry of women extended only to the most superficial aspects of femininity, the reproductive and secondary sex characteristics, from vaginas to curvaceous hips — in short, a man’s interpretation of what it means to be a woman.”

Daniel Harris isn’t about to go beat up trans women — he does claim to want them to have “full protection under the law” — but his rhetoric has more in common with those who do than he’ll admit. Take Zella Ziona, murdered by her boyfriend, Rico LeBlond, in Maryland last year. According to CBS, Ziona “began acting flamboyantly towards LeBlond and greatly embarrassed LeBlond in front of his peers.” What was the source of LeBlond’s embarrassment? Was it perhaps the same failure that Harris wants to spare her, the failure to be woman enough through, paradoxically, wanting womanhood in excess?

Or James Dixon, who beat Islan Nettles to death in 2013. Dixon had a chip on his shoulder. “A couple of days before this incident, I got fooled by a transgender and this could have led to this incident, [this] blind fury,” Dixon testified. Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice and I kill you. We’re a nation of dupes, according to Harris, and transgender people are taking advantage of us when we “insist that we not only call them ‘he’ or ‘she’ but that we treat them as if they were indeed men or women.”

I’d like to say that transgender people don’t care what Daniel Harris thinks. And in a purely theoretical sense, we don’t. So what if he doesn’t like someone’s nose job, so what if he thinks someone is too fat or too concerned with her breasts or has too strong of a jaw line. Believe me, I’m not crying myself to sleep every night because Daniel Harris doesn’t think I’m a real man. I may not even want to be a real man — and here, too, is something that Harris doesn’t consider: that some of us are happy in the middle. That some of us are happy failing at gender. Because all of us fail gender in some way. The woman who talks too loud; the man who takes to the dance floor without sufficient irony. But that’s the thing: gender is so much more complicated, so much more of a dialectical exchange between real and ideal, than Harris could ever know.

In end, however, it doesn’t matter how little we care about what Daniel Harris thinks about our genders, because words like his carry consequences. If you really believe that transgender people fail at their genders and you make it a business to say so publicly, you should know that your words resonate far off the page. If your supposed concern for transgender people masks plain old misogyny, a vitriolic relationship to femininity so deep it saturates the pores of even your most innocuous words, then you are complicit in violence. You highlight the path that leads from your vacuous think piece to some other man’s fists.