It was 2001 when I first listened to Yoko Ono’s music. I was young and quite stupid and mostly alone. I’d walk around New York with no particular aim, trekking from my job in midtown to a subway station in SoHo because I had nowhere better to be. I took my lunch (one-dollar coffee, banana) in the bakery across the street from my shitty office, where I’d read and smoke (indoors!). I was broke, but buying things made me feel alive. I’d pick up remainders at Coliseum Books, or vintage porn from a sidewalk vendor on Seventh Avenue. One day, on a whim, I bought Ono’s 1982 album It’s Alright (I See Rainbows). It was, perhaps unsurprisingly, on sale.

It was 2001 when I first listened to Yoko Ono’s music. I was young and quite stupid and mostly alone. I’d walk around New York with no particular aim, trekking from my job in midtown to a subway station in SoHo because I had nowhere better to be. I took my lunch (one-dollar coffee, banana) in the bakery across the street from my shitty office, where I’d read and smoke (indoors!). I was broke, but buying things made me feel alive. I’d pick up remainders at Coliseum Books, or vintage porn from a sidewalk vendor on Seventh Avenue. One day, on a whim, I bought Ono’s 1982 album It’s Alright (I See Rainbows). It was, perhaps unsurprisingly, on sale.

If I didn’t like Yoko Ono myself, I might think someone who called himself a fan was joking, or engaged in some other thing: adolescent contrarianism or camp, possibly diva worship of those giant Porsche sunglasses, those hats, those short shorts, those gams, the incontrovertible foreignness of Ono’s English. For a long time Ono was basically despised, the inevitable lot of someone married to a person whose fame actually may have eclipsed Christ’s. Fools hate foreigners, and fools hate women, but a lot of people who ought to know better hate the avant-garde, and a lot of people who ought to know better hate the politically engaged, and a lot of people who ought to know better hate polymaths, and Ono is all those things. I think that now the line among sophisticates is that Ono’s musical project is so idiosyncratic you can respect it without quite enjoying it, but I’ve never considered myself a sophisticate.

I associate Yoko Ono’s music with our first year of George W. Bush’s ruinous presidency, prophetess for a new year/decade/century/millennium. That September morning, I watched smoke pluming up over the Williamsburg Savings Bank (then dentist’s offices, now luxury condominiums) from my bedroom window. I strolled through Fort Greene Park, where people, no doubt driven mad by watching television, were playing tennis. That night, I listened to Ono’s album Rising, on headphones connected to my Discman.

I associate Yoko Ono’s music with our first year of George W. Bush’s ruinous presidency, prophetess for a new year/decade/century/millennium. That September morning, I watched smoke pluming up over the Williamsburg Savings Bank (then dentist’s offices, now luxury condominiums) from my bedroom window. I strolled through Fort Greene Park, where people, no doubt driven mad by watching television, were playing tennis. That night, I listened to Ono’s album Rising, on headphones connected to my Discman.

That album was suited to that day: war has long been one of Ono’s abiding preoccupations, and war was in the air. “Towns burning/ Throats choking/ Watch out/ Check out.” Indeed, I did check out. I left New York to live alone in a big empty house in the woods, where I spent months writing five hundred pages of a truly horrible novel and listening to Rising repeatedly. I had no television, I had one book (The Ambassadors, for some stupid reason), and I had nightmares almost nightly. Ono entertained me. “You are a New York Woman/ I miss you/ I miss you/ I miss you, my friend,” she sang, and it seemed like she was talking about the women who would have been my friends, if I had any.

That album was suited to that day: war has long been one of Ono’s abiding preoccupations, and war was in the air. “Towns burning/ Throats choking/ Watch out/ Check out.” Indeed, I did check out. I left New York to live alone in a big empty house in the woods, where I spent months writing five hundred pages of a truly horrible novel and listening to Rising repeatedly. I had no television, I had one book (The Ambassadors, for some stupid reason), and I had nightmares almost nightly. Ono entertained me. “You are a New York Woman/ I miss you/ I miss you/ I miss you, my friend,” she sang, and it seemed like she was talking about the women who would have been my friends, if I had any.

On one of the album’s later songs, “Where Do We Go From Here,” Ono sings, “Are we getting tired of blood and horror? Are we getting ready for God and terror?” That Rising was released in 1996 makes Ono seem prescient. I went back to New York in the spring of 2002 and found it so full of God and terror that I couldn’t take the subway, and broke down into tears when a lunatic at Pathmark called me a faggot. I never finished writing that novel.

It probably means I’m a philistine that I never simply listen to music; it’s a secondary consideration, something to accompany me on a commute, while washing dishes, on those rare horrible occasions I decide to go for a run. I respond to music emotionally rather than intellectually, which feels like a failing, if a common one. At some point a couple of years ago, I trained myself to write at night instead of during the day; it was easier to sustain focus after the children were asleep, and I was tired all the time because of the children anyway. I used music to modulate those late nights, giving those hours a rhythm: easy, then invigorating, then calming.

That nightly cycle almost always involved revisiting that first record of Ono’s I had bought. “My Man” is a daffy, earnest love song that’s almost certainly about John Lennon (“When he speaks/ all the birds come around”). It’s sung, rather than screamed — the notion of Ono as banshee isn’t an altogether fair one — and it calmed me. “Spec of Dust,” another song that’s probably about Lennon, a paean to the idea that love is timeless, made me sad. “Why do I miss you so/ if you’re just a spec of dust/ floating, endlessly, amongst a billion stars?”

That nightly cycle almost always involved revisiting that first record of Ono’s I had bought. “My Man” is a daffy, earnest love song that’s almost certainly about John Lennon (“When he speaks/ all the birds come around”). It’s sung, rather than screamed — the notion of Ono as banshee isn’t an altogether fair one — and it calmed me. “Spec of Dust,” another song that’s probably about Lennon, a paean to the idea that love is timeless, made me sad. “Why do I miss you so/ if you’re just a spec of dust/ floating, endlessly, amongst a billion stars?”

That record, with its songs of love and rage, made me remember being a dumb twenty-something, full of both: love for some theoretical boyfriend, rage at my creative/financial/professional impotence. Most feel this way as teens and get into punk rock or start a shitty band all their own, but I had an arrested adolescence, not uncommon, I think, when you grow up gay but refuse to think about it, and so I had Yoko Ono. Listening to her in my thirties, in the middle of the night, my husband and children asleep upstairs, I remembered the years in which I was without a husband, without children, and without the discipline to write a book.

I love hearing people’s advice about books to read, exhibitions to attend, films to see, but I am utterly incurious about what music people recommend, because I ask that music perform this service for me, that it entertain me in the moment while also offering some memory of a moment long passed. Dionne Warwick reminds me of those early days of parenthood, my older son lolling around on a blanket and frowning; Kate Bush’s sixth record reminds me so much of a desperate summer I spent lovelorn in Boston that I can barely bear to listen to it. It’s an imperfect way of listening, of consuming, of course; emotions ruin everything.

*

There are the songs I enjoy because they remind me of some previous time, some previous self, and there are the songs I enjoy because they are tidy, perfect texts of which I am professionally jealous. Ono has always had a flair for language. Undoubtedly her best-known work is the phrase “War is Over! If You Want It,” a line in “Happy Xmas,” the song she co-wrote with her late husband, but more famously the advertising slogan of Yoko Ono Inc., on behalf of all humanity, stark black on pure white in filthy Times Square.

There’s an unadorned clarity to her writing, which might have something to do with her long association with Fluxus, the self-serious art movement that preferred strong words and uncollectable action and performance to a traditional conception of art. The movement was big on disarming straight talk. Ono’s book Grapefruit is pure Fluxus: silly and impossible instructions for actions, process as product. I love that you still see pretty undergrads buying copies of it at the Strand every fall. This is why Ono is so great at Twitter, a medium where she has had a renaissance — she’s been able to talk directly to an audience that might otherwise not know much about her beyond the obvious.

There’s an unadorned clarity to her writing, which might have something to do with her long association with Fluxus, the self-serious art movement that preferred strong words and uncollectable action and performance to a traditional conception of art. The movement was big on disarming straight talk. Ono’s book Grapefruit is pure Fluxus: silly and impossible instructions for actions, process as product. I love that you still see pretty undergrads buying copies of it at the Strand every fall. This is why Ono is so great at Twitter, a medium where she has had a renaissance — she’s been able to talk directly to an audience that might otherwise not know much about her beyond the obvious.

Ono’s oeuvre contains many turns of phrase that I envy — one of my favorite songs is her “All Day Long I Felt Like Smashing My Face in a Clear Glass Window” which has the very clarity that makes her tweets, and Grapefruit, so perfect. Her songs are poetry that never sound much like poetry, unlike many of Morrissey’s songs, which I can never listen to when I work because I end up writing ersatz Smiths lyrics, with opaque references to the royal family.

But of course the real standard by which you measure a song is more animal than intellectual. In the story “Signs and Symbols,” Nabokov wrote of referential mania, the delusion that all the world — the most innocuous action, the simple existence of some thing — is somehow about you. I imagine we all suffer from this mania when it comes to judging art (hence this passion to see ourselves in the pages of a book) but of course, there’s some other, ineffable thing to the equation. Ono has written a lot of great songs. She’s also written a lot of not great songs, as have most people engaged in this pursuit. The sound of some of Ono’s songs — “She Gets Down on Her Knees,” “I Have a Woman Inside My Soul,” “Loneliness,” “Sisters O Sisters” — simply works for me; music and the savage beast and all that.

Ono can and does caterwaul, and I get why people snicker at that. It’s aggressive and weird and disorienting and to laugh at it is an obvious response, if a superficial one. The live version of “Don’t Worry Kyoko,” on Ono’s 1972 record with Lennon, Some Time in New York City, is bracing, electric, astonishing. You needn’t know the backstory — Kyoko is Ono’s daughter, the subject of a custody dispute so bitter they were wholly separated for decades — to hear the raw expression of pain leavened by maternal comfort in Ono’s screams. In the soundtrack to Ono’s remarkably unsettling short film “Fly,” she delivers a vocal performance that defies description. It’s worth listening to, even if you can only manage to listen to it once; I think the same can be fairly said of the composer Kaija Saariaho or many other difficult artists. But leave aside this aggressively avant-garde work if you like; “The Death of Samantha” and “Walking on Thin Ice” are great rock and roll songs. It’s incredible to me that the same artist could manage to have made both.

Ono can and does caterwaul, and I get why people snicker at that. It’s aggressive and weird and disorienting and to laugh at it is an obvious response, if a superficial one. The live version of “Don’t Worry Kyoko,” on Ono’s 1972 record with Lennon, Some Time in New York City, is bracing, electric, astonishing. You needn’t know the backstory — Kyoko is Ono’s daughter, the subject of a custody dispute so bitter they were wholly separated for decades — to hear the raw expression of pain leavened by maternal comfort in Ono’s screams. In the soundtrack to Ono’s remarkably unsettling short film “Fly,” she delivers a vocal performance that defies description. It’s worth listening to, even if you can only manage to listen to it once; I think the same can be fairly said of the composer Kaija Saariaho or many other difficult artists. But leave aside this aggressively avant-garde work if you like; “The Death of Samantha” and “Walking on Thin Ice” are great rock and roll songs. It’s incredible to me that the same artist could manage to have made both.

*

My children are older now, and I’ve gone soft, the abbreviated schedule of their infant sleep somehow forgotten. A few weeks ago, I tried to reclaim the night for myself, those stretches of hours that had proved so fertile, so essential, only a couple of years ago. It was in part superstition and in part the simple need to keep myself awake, but I tried to recreate the specific rhythm of those productive nights: ease, then energy, then quietude. I began with the Brandenberg Concertos, but Bach’s cool mathematics often make me sleepy. I played “Don’t Worry Kyoko,” to rouse myself, then the computer offered me “Is Winter Here to Stay?,” a song of Ono’s that I’ve long liked. I was surprised to find that what I remembered, with a sensory clarity that was almost frightening, was not that time alone in a far-away house in 2001 but a similar night alone in the house I still call home. I remembered two years ago, I remembered a tumbler of watery whisky, damp with condensation, the oppressive heat of New York in June, the lack of absolute silence even at two o’clock in the morning, the reassuring sense that everyone I loved was asleep upstairs.

It’s a confounding thing that art can endure. I don’t mean over the ages — what does that matter, we’re destroying the planet — but in our lives. Art is a conversation between you and someone you’ve probably never met, and that conversation can continue for so long. Yoko Ono, who once reminded me of being twenty-three and watching the world blow up, now reminds me of being thirty-six, old enough to have built a world anew for myself. I don’t know why this should be, but I’m grateful that it is. When she screams don’t worry, I almost believe her.

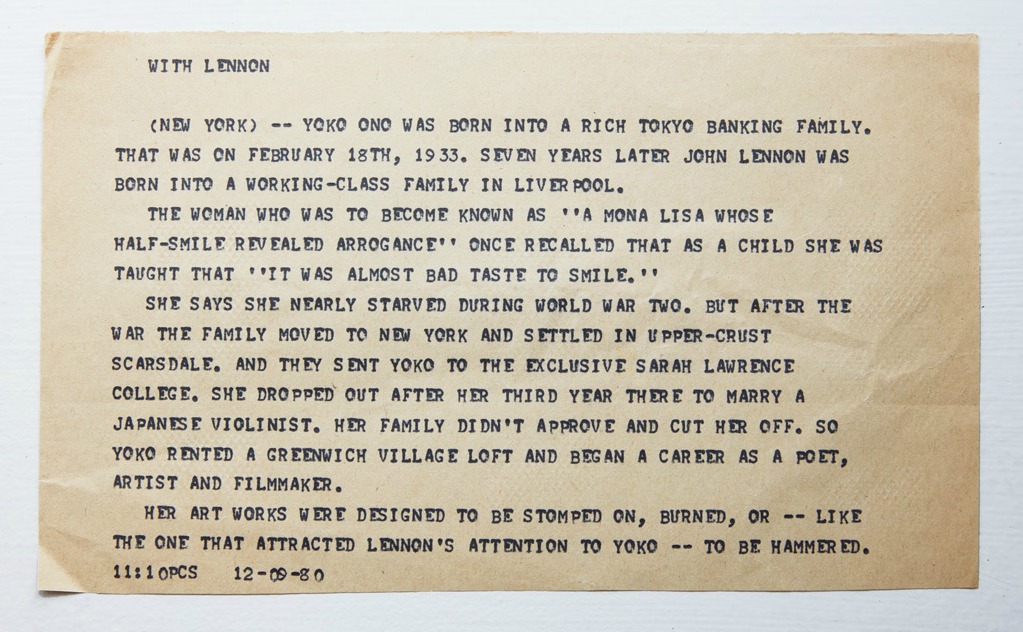

Image: I bought this oddity on eBay in the middle of the night. It purports to be a wire service news bulletin, and I can’t imagine it’s not authentic because who would fake such a thing? The manner in which Ono is discussed in this says a great deal. I like to imagine Ono, who has played with language throughout her long career, would be amused at rather than hurt by its casual cruelty. It’s dated the day after John Lennon was murdered.