1.

On the cover of his When I Was a Photographer, we see a studio self-portrait of Félix Nadar in a hot air balloon. The French artist gazes into the distance like Hernán Cortés staring out over the Pacific, binoculars at the ready lest something should warrant closer inspection. He is also fully clothed. When he became the first person to capture an image from the air, he was stark naked. Low on gas, he had closed his balloon’s valve on the ascent and began lightening the load, dropping his trousers, shoes and everything else except his camera onto the ground below. Shivering as he rose to an altitude of 80 meters in his “improvised laboratory,” he produced the world’s first successful aerial photograph. (In his many previous failed attempts, the balloon’s gas valve had been open, which had contaminated the developing bath: “silver iodide [from the bath] with hydrogen sulfur, a wicked couple irrevocably condemned to never produce children.”) Nadar, it could thus be said, was a pioneer in both aerostatic and nude photography.

This triumphant, naked flight is one of the spirited accounts in When I Was a Photographer, Nadar’s 1900-book translated and introduced by Eduardo Cadava and Liana Theodoratou. Nadar’s is not one of those conventional memoirs in which the orderly progression of reminiscences serves to obscure rather than illuminate the subject. Rather, Nadar relates an assortment of vignettes, some approaching the central subject head-on, others slantwise, but all in an engagingly conversational style. Reading Nadar’s eccentric musings brought to mind Max Beerbohm’s praise for the lively, unorthodox prose of James McNeill Whistler’s The Gentle Art of Making Enemies: “It matters not that you never knew Whistler, never even set eyes on him. You see him and know him here.” Like Whistler’s, Nadar’s writing is revelatory in the literal sense of the word.

This triumphant, naked flight is one of the spirited accounts in When I Was a Photographer, Nadar’s 1900-book translated and introduced by Eduardo Cadava and Liana Theodoratou. Nadar’s is not one of those conventional memoirs in which the orderly progression of reminiscences serves to obscure rather than illuminate the subject. Rather, Nadar relates an assortment of vignettes, some approaching the central subject head-on, others slantwise, but all in an engagingly conversational style. Reading Nadar’s eccentric musings brought to mind Max Beerbohm’s praise for the lively, unorthodox prose of James McNeill Whistler’s The Gentle Art of Making Enemies: “It matters not that you never knew Whistler, never even set eyes on him. You see him and know him here.” Like Whistler’s, Nadar’s writing is revelatory in the literal sense of the word.

2.

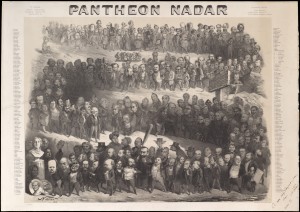

Born Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, Nadar moved from his native Lyon to Paris in 1838, where as a man of letters on the make he became a fixture of the Latin Quarter’s bohemian set. The talented eccentric would eventually turn his attention from journalism to caricature, prompting one illustrator, Paul Gavarni, to exclaim: “Ah! we are done for now that Nadar has learned to draw.” Nadar was prolific, composing caricatures for such publications as Charivari and Le Journal Pour Rire and pouring his considerable energy into the “Panthéon Nadar” (1854), in which the brightest of Paris’s literary lights — nearly 300 in all — appear in a tightly-packed, snaking line. The work is a marvel of compression, the distinctive faces of the teeming cast standing out in stark relief from the collective, sinuous body of the French intelligentsia.

Nadar prepared for the Panthéon project by photographing some of his subjects, and soon his artistic focus shifted yet again, this time to photographic portraiture, which, like his comicalities, sought to capture the “moral and intellectual” nature of the subject. Though his studio was primarily a commercial outfit, Nadar could never resist a technological challenge. Apart from his foray into aerostatic photography, he experimented with artificial lighting in the catacombs and sewers beneath Paris’s streets, embarking on a katabatic “journey through this outlet of the infinite putridness of a great capital.” Nadar and his team lugged their equipment through the stygian mire and staged shots that could take up to 18 minutes of exposure. In the final minute of one such exposure, “a cloud rising from the canal came to veil our photograph — and how many imprecations, then, against the beautiful woman or the good man above us, who, without suspecting that we were there, chose that exact moment to replenish the water in their bathtub!” The ruined plate goes out with the bathwater.

Nadar’s life was full of exploits. In Sidetracks, Richard Holmes notes that Nadar and 500 Republicans attempted to liberate Poland from the Prussians in 1848. As if providing instructions for fellow caricaturists, Nadar’s fake passport read: “Age 27 years, height 1.98 meters, hair rust red, eyes protuberant, complexion bilious.” Nadar found himself resisting the Germans once again, this time during the 1870-71 siege of Paris when he oversaw the effort to transport mail over enemy lines in hot air balloons. Neither snow nor rain nor the Prussian army…Nadar’s “patriotic satisfaction” mixed with wry bemusement over his new role:

Certainly never, after passing through diverse professions in our life, never would we have imagined our latest incarnation under the aesthetic of a varnished cockaded hat and a mailman’s bag on the belly.

Still adventurous in his old age, Nadar would plunge himself, camera in hand, into an unleashed swarm of bees, trusting only the blithe assurances of a Provencal apiarist (“They are sheep, sir, real sheep!”) that he would emerge unscathed:

Still adventurous in his old age, Nadar would plunge himself, camera in hand, into an unleashed swarm of bees, trusting only the blithe assurances of a Provencal apiarist (“They are sheep, sir, real sheep!”) that he would emerge unscathed:

They have always been alluring for me, these kinds of expeditions: it seems that the adventure whistles for me… — and then once again, as my friend Banville would say, it is so much fun to get mixed up in something that does not concern you: and what’s more, well, my tempter appeared to be so sure of his business, of our business…

In that shift from his to our we can glean the essence of the photographer, who makes a life getting up in his subjects’ business, so to speak.

Nadar’s reverence for the medium and its skilled practitioners is undeniable; that for his everyday clients nonexistent. Nadar compares a colleague’s studio, a “fateful hut” perched on a Parisian rooftop, to “the Greek temple of the Odeon.” Most of the clients he mentions, however, are distinctly unheroic or comically clueless. One orders a portrait, pays, and leaves. Nadar chases him down and tells him he must actually pose. “Ah…As you wish…But I thought that this was enough…” In general, men suffer from an infatuation with their photographic appearance “pushed to the point of madness;” one spends a sleepless night fretting over a single misplaced hair in his proofs. Men might be the worst offenders, but all subjects present problems:

So good is everyone’s opinion of his or her physical qualities that the first impression of every model in front of the proofs…is almost inevitably disappointment and recoil (it goes without saying that we are talking here of perfect proofs).

In that wonderful parenthetical, Nadar counters his client’s vanity with a display of his own.

3.

Nadar’s breezy style at times belies the book’s gnomic core, in which the “astonishing and disturbing” photographic technology inspires exultation and anxiety in equal measure. (As the translators note, Nadar’s reflections on art in the age of mechanical reproduction attracted the attention of Walter Benjamin, who refers to certain passages in The Arcades Project.) Nadar believed himself to be living in “the greatest of scientific centuries,” an era in which technologies arose with dizzying speed:

Such is in fact the glorious haste of photography’s birth that the proliferation of germinating ideas seems to render incubation superfluous: the hypothesis comes out of the human brain in full armor, fully formed, and the first induction immediately becomes the finished work.

The reference to Athena’s birth from Zeus’s head resonates when Nadar describes the godlike element of photography, which

finally seems to give man the power to create, he, too, in his turn, by materializing the impalpable specter that vanishes as soon as it is perceived, without leaving even a shadow on the crystal of the mirror, or a ripple in the water in a basin.

One detects here, not for the last time, a hint of the demonic: photography as a dark art.

Nadar’s recollections begin with the initial unease brought about by photographic technology, “the contagion of…first recoil” that afflicted even “beautiful minds” such as Honoré de Balzac, Théo Gauthier, and Gérard de Nerval. Balzac, for instance, subscribed to the theory that “each body in nature is composed of a series of specters, in infinitely superimposed layers, foliated into infinitesimal pellicules, in all directions in which the optic perceives this body.” Each “Daguerreian operation” would thus seize one of these spectral layers until a body could waste down to nothing. The ever-playful Nadar seizes on this theory to needle his friend about his weight — “Balzac had only to gain from his loss, since his abdominal abundances, and others, permitted him to squander his “specters” without counting.” (The playground taunt would go something like, Yo Mama is so fat, I could Daguerreotype her all day and she still wouldn’t disappear!)

From Balzac’s “terror before the Daguerreotype,” Nadar moves on to the demonic perceptions of photography:

This mystery smelled devilishly like a spell and reeked of heresy: the celestial rotisserie had been heated up for less. Everything that unhinges the mind was gathered together there: hydroscopy, bewitchment, conjuration, apparitions. Night, so dear to every thaumaturge, reigned supreme in the gloomy recesses of the darkroom, making it the ideal home for the Prince of Darkness. It would not have taken much to transform our filters into philters.

The passage is tongue-in-cheek, but Nadar repeatedly flirts with occult rhetoric to describe his art. Take, for example, his attempts at underground photography, described in the language of esoteric exploration:

The subterranean world was opening up an infinite field of operations no less interesting than the telluric surface. We were going to penetrate, to reveal the mysteries of the deepest, the most secret caverns.

When Nadar leaves the subterranean world and takes to the skies, his initial inability to capture a clear image makes him feel “as if under a cast spell,” unable to “get out of these opaque, fuliginous plates, from this night that pursues me.”

Generally lighthearted though he is, Nadar is haunted by sinister faces and spectral gazes. One chapter involves Nadar’s mysterious entanglement with a mountebank named Mauclerc, one of whose cons involves long-distance portraiture (i.e., a camera in Paris produces an image of a subject in Toulouse.) Years later, Nadar is visited by a young man claiming to have performed the same feat, at which point the has an eerie vision of Mauclerc and his “hideous smile:”

..the features of my noble Hérald [a friend] and the honest face of the young worker were merging, blending into a kind of Mephistophelian mask from which appeared a disquieting figure that I had never seen before but recognized immediately: Mauclerc, deceitful Mauclerc…mockingly handing me his electric image…

Long-distance photography at last! By conjuring the face of his distant tormentor out of thin air, Nadar’s feverish imagination has performed the impossible feat promised by the conmen.

In another vignette, Nadar receives a “funeral call” to photograph a recently deceased man. “Surely, this man had been loved…” begins a chapter that will end with an expression of “hatred and contempt.” As Nadar delivers the print to the deceased’s wife and mother-in-law, whose “hellish gaze bore into [him] relentlessly,” he is compelled to admit that he has already given out a print to another mourner: the man’s mistress. Here Nadar witnesses the perils of reproduction. The copy is just one of a (potentially) infinite series, but its circulation destroys the wife’s own image of her husband. She collapses, and Nadar, crushed to have “unwillingly caused so much pain,” is forever after haunted by yet another specter troubling the photographer’s regard:

How many, many times have I found her unexpectedly, at a street corner, at another, everywhere, suddenly focused upon me, an always living reminder of that atrocious hour — motionless and piercing me with her ashen eyes — which I still see…

The most dramatic display of photography’s dark side comes in a chapter entitled “Homicidal Photography.” There Nadar recounts the sensational case of a pharmacist, his bored wife, and a scheming assistant who cuckolds the former, jilts the latter, and robs both. Nadar traces the characters of this “insipid epic of little people” as they develops with the “fateful monumentality and progression of a Shakespeare drama…” Once the wife confesses her adultery, the pharmacist enlists her and his brother to lure the assistant to a remote location, stab him to death, drop his corpse from a bridge, and return to Paris. According to Nadar, a sure acquittal, a simple case of “adultery committed, adultery avenged.” Until, that is, a journalist photographs the decomposing body. Nadar describes this body in vivid detail, but prose is prose, no matter how sickening. Photography exposes the full horror of the “drowned man in total putrefaction, so abominably fashioned that the humor form soon becomes illegible.”

The drama, “monstrous…and sensational in its staging,” riles up the public such that only one outcome is possible: “It is the photograph that has just pronounced THE SENTENCE — the sentence without appeal: “DEATH!” Nadar personifies photography as an avenging angel who, through the accursed image, makes her terrible will known. “But PHOTOGRAPHY wanted it this way this time, ” Nadar concludes, stoically accepting the whims of the capricious demiurge to whom he is, or was, in thrall.

4.

The passages I have selected attest to Nadar’s peculiar temperament, his buoyant lugubriousness. Nadar threw himself into his art with the same abandon with which he followed the apiarist into the beehive:

We find ourselves enveloped, obscured, blinded, lost in the midst of these myriads of sword-bearers, titillated everywhere…by these moving effervescences — an immersion into a universal touch.

This tableau is emblematic of Nadar, an artist forever immersing himself — in a swarm of bees, in the “thickest part of a cloud,” in the Piranesian sewers of Paris, in the mysteries of photography, in darkness and in light.