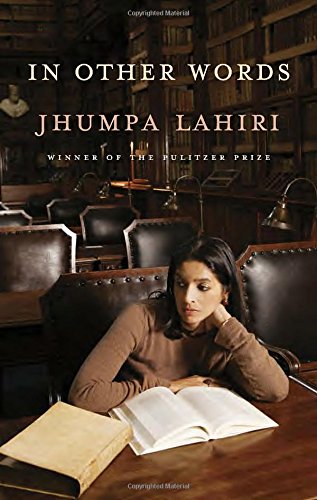

I started Jhumpa Lahiri’s new memoir, In Other Words, expecting to find a story about the joys and struggles of learning Italian as an adult, and as a writer. I thought there might also be elements of travelogue, because I knew Lahiri had moved to Rome to master the language. But Lahiri did not write the book I was expecting — and which I think many other readers might be primed for. Instead, she has written an elegant, if somewhat oblique, memoir about creative crisis.

Let me be clear: Lahiri never uses the word “crisis” in her memoir, and I don’t mean to invoke it in an overly dramatic way, or to imply that Lahiri is in the midst of any kind of personal turmoil. I mean crisis in the sense of a turning point, and this book seems most animated by questions of change — specifically, Lahiri’s desire to “take another direction” in her fiction. Immersing herself in Italian for three years was her way of forcing herself to change her relationship to language and storytelling. And it was a dramatic immersion: while living in Rome, she did not speak, write, or read in English. Additionally, she stopped reading in English for six months before her departure. It’s this last deprivation that struck me as most radical. To live in an English-speaking country and not partake of its literary offerings seems difficult for anyone, let alone a writer. Lahiri uses religious language to describe this choice:

From now on, I pledge only to read in Italian. It seems right, to detach myself from my principal language. I consider it an official renunciation. I’m about to become a linguistic pilgrim to Rome. I believe I have to leave behind something familiar, essential. Suddenly none of my books are useful anymore. They seem like ordinary objects. The anchor of my creative life disappears, the stars that guided me recede.

The above excerpt is translated from Italian, the language that Lahiri has been writing in for the past three years. Her memoir was first published in Italy, last year, and is now being released in the U.S. in a dual-language format, with the English translation by Ann Goldstein (best known for her translation of Elena Ferrante’s Neopolitan novels). Initially, Lahiri thought that she might translate her own work, but after translating one of her lectures from Italian, she found that her English was too strong, and that it was too tempting to rewrite everything. In her author’s note, Lahiri explains that she wanted the translation to “render my Italian honestly, without smoothing out its rough edges, without neutralizing its oddness, without manipulating its character.”

The problem with Lahiri’s Italian is not that it is odd; instead it is sometimes smooth to the point of vagueness. In English, she is a wonderfully precise writer, but in Italian that precision is gone and her sentences can feel watered down. When she’s getting into complicated issues of identity and exile, I often wished she could switch to English. At the same time, her Italian has a simplicity that is very appealing — and revealing. With so many linguistic limitations, Lahiri has nowhere to hide. When she first moves to Rome, she was compelled to write a diary in Italian, even though her written Italian was still rudimentary:

I write in terrible, embarrassing Italian, full of mistakes. Without correcting, without a dictionary, by instinct alone. I grope my way, like a child, like a semiliterate…I don’t recognize the person who is writing in this diary, in this new, approximate language. But I know that it’s the most genuine, vulnerable part of me.

Throughout In Other Words, Lahiri works toward this “genuine, vulnerable” state. One reason she’s attracted to Italian, and to the project of learning a new language, is that it makes her feel childlike, and it makes writing feel “secret” and special. Another reason she’s attracted to Italian is that it’s a language that she chose for herself. Lahiri grew up learning two languages, Bengali and English. At home, she spoke Bengali to please her parents, who also spoke English but wished to preserve their native tongue. At school, she excelled in English to please her teachers. The two languages rarely overlapped, and when they did, they clashed. Although her parents spoke English well, their accents were strong, and Lahiri found herself speaking for them in public; at school, her ability to speak Bengali went unnoticed and unquestioned — until her parents called at a friend’s house, and her private life was revealed. When she finally encountered Italian, the language represented a freedom from duty:

I had to joust between those two languages until, at around the age of twenty-five, I discovered Italian. There was no need to learn the language. No family, cultural, social pressure. No necessity.

Learning Italian also represents a kind of freedom for Lahiri in terms of her writing career. She became famous when her first book, Interpreter of Maladies, won the Pulitzer Prize. The award changed her life, but it also changed her relationship to her creative process:

Learning Italian also represents a kind of freedom for Lahiri in terms of her writing career. She became famous when her first book, Interpreter of Maladies, won the Pulitzer Prize. The award changed her life, but it also changed her relationship to her creative process:

Since then I’ve been considered a successful author, so I’ve stopped feeling like an unknown, almost anonymous apprentice. All my writing comes from a place where I feel invisible, inaccessible. But a year after my first book was published, I lost my anonymity.

Reading those lines, I found myself thinking of the recent film The End of the Tour, which I reviewed favorably for this site, in part because I thought it did such a good job of discussing literary fame. That movie addresses the impending worldwide renown of David Foster Wallace, who, having just spent several weeks playing the part of Famous Author during his book tour for Infinite Jest, has to figure out how to get back to the oblivious, giddy part of himself that loves to make up stuff. The drama (and comedy) is in watching him try to escape himself while a reporter sticks a microphone in his face.

Reading those lines, I found myself thinking of the recent film The End of the Tour, which I reviewed favorably for this site, in part because I thought it did such a good job of discussing literary fame. That movie addresses the impending worldwide renown of David Foster Wallace, who, having just spent several weeks playing the part of Famous Author during his book tour for Infinite Jest, has to figure out how to get back to the oblivious, giddy part of himself that loves to make up stuff. The drama (and comedy) is in watching him try to escape himself while a reporter sticks a microphone in his face.

Lahiri’s memoir is also haunted by the dream of escape, especially in the two short pieces of fiction that she includes as stand-alone chapters. They are by far the most emotionally resonant pieces of writing in the book, which goes to show how well the mask of fiction works for her. Lahiri says that writing in Italian is another mask for her, and it’s interesting to note how her stories in Italian differ from her stories in English. With only two very short fictions it’s hard to draw conclusions, but I think it’s fair to say that they are much more dreamlike than her previous work. In a brief passage in which Lahiri analyzes the autobiographical elements of her past stories and novels, she says that writing in Italian has allowed her to “move toward abstraction:”

The places are undefined, the characters are so far nameless, without a particular cultural identity. The result, I think, is writing that is freed in certain ways from the concrete world. I now construct a less specific setting…Writing in Italian, I feel that my feet are no longer on the ground.

For Lahiri, leaving the concrete world means leaving behind her parents’ experience, and the world they lived in. It’s a world she says she has tried to reconstruct in her fiction as a way of bridging the divide between India and America, the past and the present. She admits that it took her “a long time to accept that my writing did not have to assume that responsibility.” As a reader, I’ve always felt that sense of responsibility lurking in her stories, though I wouldn’t say it’s been detrimental. It may be what gives her prose its clarity and depth. Still, it’s refreshing to hear that Lahiri felt the need to break free. She describes In Other Words as “the first book I’ve written as an adult, but also, from the linguistic point of view, as a child.” That’s probably the best description of this book that anyone can give; it captures its in-between, searching qualities, and the way that it hints at new work to come.