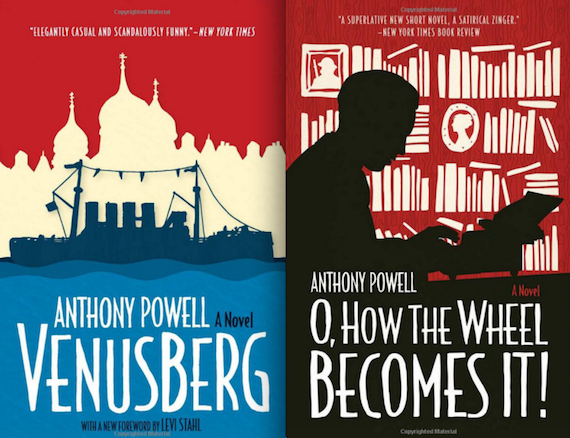

Love and work are the subjects the British novelist Anthony Powell covers in O, How the Wheel Becomes It! and Venusberg two slim novels, recently reissued by University of Chicago Press, which bracket his monumental 12-volume Dance to the Music of Time, written over the course of almost 15 years, from 1957 to 1971. Still relatively lesser known in the United States, the Dance series is one of the great achievements of 20th-century literature, and perhaps the greatest portrayal of (mostly upper-class) British life from approximately the 1920s through the 1960s.

In his introduction to Venusberg, which Powell published in 1932 when he was only 27, Levi Stahl astutely notes the differences between Powell and the author whom he is often thought to resemble, Evelyn Waugh. Both wrote about the educated upper classes and had enormous skill at skewering their pretensions and obsessions. But where Waugh was highly self-conscious of his status as an outsider and desperately wanted to be included among his subjects even as he savaged them, Powell developed a different style. He writes more as an insider but one removed from the social whirl by almost incomprehensibly sensitive social antennae. “Waugh’s books are arguably funnier (though some sections of Dance hold their own), but they also have an angry, cruel, even nihilistic strain. Waugh’s satire is scorching, leaving little behind but blasted ground. Powell, on the other hand, while refusing novelistic happy endings, presents a more hopeful outlook: his early novels tend to include at least one character who yearns, if fitfully, to live a life with meaning.”

The Brit abroad novel in this era of Brick Lane and a multiethnic Britain may seem the most tiresome of tropes. Moreover in this era of YouTube, cell phones, and Snapchat, the possibility of real strangeness or feelings of isolation in foreign travel are almost impossible to recover, in addition to the sometimes unpleasant colonial overtones some such novels evoke. In Venusberg, however, the charm and humor of such a setting comes through, even as Powell searches after deeper themes. Venusberg is the name of a hapless Baltic town to which the main character, a writer named Lushington, goes purportedly on assignment. In fact, he is running from a woman, Lucy, whom he loves but who loves another. Lushington’s fellow travelers are refugees from their own sort of romance, homes, and countries they left or were forced to leave (or as is the case with a mother and daughter traveling together, a Habsburg Empire that is no more.)

The Brit abroad novel in this era of Brick Lane and a multiethnic Britain may seem the most tiresome of tropes. Moreover in this era of YouTube, cell phones, and Snapchat, the possibility of real strangeness or feelings of isolation in foreign travel are almost impossible to recover, in addition to the sometimes unpleasant colonial overtones some such novels evoke. In Venusberg, however, the charm and humor of such a setting comes through, even as Powell searches after deeper themes. Venusberg is the name of a hapless Baltic town to which the main character, a writer named Lushington, goes purportedly on assignment. In fact, he is running from a woman, Lucy, whom he loves but who loves another. Lushington’s fellow travelers are refugees from their own sort of romance, homes, and countries they left or were forced to leave (or as is the case with a mother and daughter traveling together, a Habsburg Empire that is no more.)

The long boat trip gives Powell the opportunity to indulge his finely tuned sensibilities to differences in class, wealth, and station, and to develop what Stahl describes as “his remarkable talent for grotesquerie,” though one leavened by a humane sympathy. Thus his protagonist finds among the passengers a disaffected (and possibly fraudulent) count and others thrown about by the disaster of post-World War I Europe. Included among these is Ortrud Mavrin, a married Austrian woman with whom he begins an affair. Inevitably, Lushington befriends her husband, an older professor, with some comic results. Once in Venusberg, he becomes entangled with a member of the British diplomatic delegation, da Costa, who is his rival for his Lucy’s affections. Other figures include the valet Pope, possibly fake Russian aristocrats, and various nobles, soldiers, businessmen, and bureaucrats who operate in a semi-totalitarian political environment.

The love story that is the moving plot of the novel focuses on whether Lushington will continue to pursue his indifferent object of affection at home, or follow Mavrin, the European lady of mysterious background. This is perhaps a metaphor for British writers seduced by European modernism (which Powell by and large was not), or more generally the exoticism the Continent held for many British. Venusberg is, in legend, a place of seduction that captivates its admirers who must tear themselves away to return home, and the tension in the novel is how, or whether, Powell will have Lushington make the break.

Wheel, the first novel Powell published after completing Dance, has a decidedly smaller geographical ambit, but a much longer temporal one. Powell excels at the long arc; what makes Dance most compelling is the realistic way Powell describes aging and the passing of years, with all the sexual, professional, and social triumphs and disappointments those years offer. Powell makes us feel both weighted with the passage of time and also satisfaction at the unfolding of full adult lives, which I think is perhaps Powell’s real lasting literary gift.

Wheel follows a writer and critic named G.F.H. Shadbold and the petty and at times absurd world of literary culture. Powell knew this world well, and his send-up of literary pretension is classic. Shadbold is haunted and embarrassed by the memory of a half-forgotten novel of a dead man whom we would now term a “frenemy,” a schoolmate turned stockbroker named Cedric Winterwade. Shadbold has himself becomes something of a middling literary figure, with early promise but who chose instead a more certain if unimaginative career; after “the slimmest of slim volumes of verse,” and some indifferently-received novels, Shadbold settled into something like literary respectability.

Notwithstanding the comparative leanness of his output Shadbold was not to be dismissed as a lightweight, a mere hack. He has worked hard reviewing other people’s books up hill and down dale, tirelessly displayed himself on the media and elsewhere…[and] also always prepared to offer views on marginally political subjects for which he was less accredited by instinct.

Shadbold married a writer of potboiler detective novels, who is much more successful than he. However, Winterwade comes to dominate his thoughts. Shadbold learns Winterwade kept a diary in which it is revealed he was the more prodigious lover when they were younger men together, including having an affair with a woman Shadbold himself desired. This revelation raises old feelings of sexual jealousy, even after a remove of years, especially when the woman, Isolde, comes back late in Shadbold’s life; in the process, he learns Winterwade was in some respects a better man than he. Moreover, Winterwade’s literary fortunes are rising on the basis of that one novel, decades after his death. Winterwade retains the promise of young man cut down before his prime, while Shadbold must struggle with the realities of a writing life that has its share of grubbiness and self-promotion. Isolde pleads with Shadbold to help resuscitate Winterwade’s reputation.

Stahl is right that neither of these books is likely to eclipse the magnificent work that is Dance. However Venusberg is valuable because we see Powell working out perspectives that would later form the basis of Dance in the form of the novels’ narrator, Nick Jenkins. But it is the work of a young man and some of the dialogue and scenes, while surely sharp at the time, do not carry the same resonance today. But for those not yet ready to tackle Dance, Wheel is a work of the mature Powell, very sensitive to those unforeseen changes in fortune or circumstance that occur throughout life and which give the book its title.