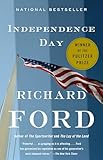

As I rode the train home from work one afternoon a little over a year ago, I read the “gnostic truth of real estate” put forth by the realtor Frank Bascombe in Independence Day:

People never find or buy the house they say they want. A market economy, so I’ve learned, is not even remotely premised on anybody getting what he wants. The premise is that you’re presented with what you might’ve thought you didn’t want, but what’s available, whereupon you give in and start finding ways to feel good about it and yourself.

A moment later — timing that would have been ham-fisted had it taken place in a novel — my phone buzzed with a text from my husband. “Pack your bags” it read, accompanied by screenshot from Redfin showing a dilapidated property with a “sold” banner plastered across. We had gone to look at this house the previous week — a teardown monstrosity in an unhip San Francisco neighborhood adjacent to our own unhip San Francisco neighborhood. Listed for $338,000, at that moment the lowest price in the city, the house was called a “contractor’s special;” two of its three bedrooms were qualified on the listing agent’s half-assed flier as “legality unknown.” When we went to the open house, the same agent eyed my eight-months-pregnant stomach and advised me to cover my mouth and nose before stepping inside. My husband’s screenshot indicated that this house had been purchased by someone for $550,000, ostensibly in cash. Add to this the cost, whatever that should happen to be, of building an entirely new house in its place.

A moment later — timing that would have been ham-fisted had it taken place in a novel — my phone buzzed with a text from my husband. “Pack your bags” it read, accompanied by screenshot from Redfin showing a dilapidated property with a “sold” banner plastered across. We had gone to look at this house the previous week — a teardown monstrosity in an unhip San Francisco neighborhood adjacent to our own unhip San Francisco neighborhood. Listed for $338,000, at that moment the lowest price in the city, the house was called a “contractor’s special;” two of its three bedrooms were qualified on the listing agent’s half-assed flier as “legality unknown.” When we went to the open house, the same agent eyed my eight-months-pregnant stomach and advised me to cover my mouth and nose before stepping inside. My husband’s screenshot indicated that this house had been purchased by someone for $550,000, ostensibly in cash. Add to this the cost, whatever that should happen to be, of building an entirely new house in its place.

At the time, my husband and I lived in a rented, one-bedroom, 750-square-foot house that, like any standalone single-family dwelling in San Francisco, is not subject to rent control. When we learned that we were expecting a baby, we thought we should try to find something with more space (and rent control). Our landlady, who we think was born in the 1930s, cautioned us against a month-to-month lease. Her health was not good, she told us, and she mentioned, not for the first time, an ominous set of people she called “heirs” who would swoop in from the Central Valley and sell the house out from under us in the event of her death. She also told us that she had lived in the house with her parents until she was 23 years old, sleeping in the small dining room. Her counsel notwithstanding, obsessed with bourgeois aspirations of a second bedroom, we went month-to-month and began looking at Craigslist listings. The appearance of heirs, it turns out, would cast us — with baby, two cats, student loans, and no car — into a rental market where a transit-accessible two-bedroom apartment could exceed $5,000 per month in San Francisco and $3,000 in the East Bay.

Ludicrous prices are old hat to people in the Bay Area, who find themselves in the tiresome position of having thoroughly exhausted the topic of the housing situation but being nonetheless unable, most of the time, to talk about anything else. That is a feature of housing bubbles; in Life Would Be Perfect If I Lived in that House, Meghan Daum’s account of her real estate travails in Los Angeles circa 2004, she wrote: “At the risk of making a perverse and offensive comparison, I truly don’t think I’d observed so much absorption with one topic since the attacks of September 11, 2001.”

Ludicrous prices are old hat to people in the Bay Area, who find themselves in the tiresome position of having thoroughly exhausted the topic of the housing situation but being nonetheless unable, most of the time, to talk about anything else. That is a feature of housing bubbles; in Life Would Be Perfect If I Lived in that House, Meghan Daum’s account of her real estate travails in Los Angeles circa 2004, she wrote: “At the risk of making a perverse and offensive comparison, I truly don’t think I’d observed so much absorption with one topic since the attacks of September 11, 2001.”

We punched numbers into questionable online mortgage calculators and began touring open houses. Houses that listed for $279,000 and sold for $365,000 (East Oakland). Houses that listed for $365,000 and sold for $500,000 (West Oakland). Houses that listed for $499,000 and sold for $700,000 (San Francisco, barely). And these were the low, low prices of 2014. Median home prices reached $1.3 million at the end of last year.

People who have actually experienced home-ownership advise the uninitiated against getting romantic about it. But when you have a bun in the oven and are looking at Craigslist rentals, it is easy to invest the condition with near-sacred profundity (even before totting up the tax breaks that the government has seen fit to bestow upon the property-owning class). I began placing an outsize burden on every undistinguished property we saw; every dubious condo, every termite-eaten hovel miles from the train, none of which we could afford in any case. I pictured the dour heirs, and our growing family in one of the illegal basement in-laws listed for more than our current rent. Like V.S. Naipaul’s unforgettable Mr. Biswas, it seemed critical to find a place to call our own: “How terrible it would have been…to have lived without even attempting to lay claim to one’s portion of the earth; to have lived and died as one had been born, unnecessary and accommodated.”

Unlike that of Mr. Biswas, though, this is the housing account of an intensely privileged person, in both the local and the world-historical sense. We began our search at a time when the U.S. news was just starting to register the desperate people streaming out of Syria, when there were already one million displaced Syrians in Lebanon alone. A month before the baby was born I watched a presentation at work about an entire nation’s middle class decimated in only a couple of years — a cataclysm that will take generations to repair. And this is only the most recent and the most vivid cataclysm. There are people who have been living in camps for decades — people whose children and whose children’s children will be born outdoors.

In our local context, we are privileged because we do not live in a state of economic precarity, like many people in San Francisco and the East Bay who are being rapidly pushed out (often by people like us sniffing around for cheaper housing). Low-income people are disproportionately affected by the outlandish housing costs, and while it is a nice feature for us to live near family and friends, it’s a necessity for people who cannot afford regular childcare or do not get paid sick time. Just last Monday, activists shut down the Bay Bridge in a truly breathtaking action, protesting not only police killings of black people, but gentrification; first on their list of demands was “The immediate divestment of city funds for policing and investment in sustainable, affordable housing so Black, Brown and Indigenous people can remain in their hometowns of Oakland and San Francisco.” The housing concerns of people with a statistically high household income are not in and of themselves compelling, as this author points out, and if we have to leave the Bay Area we will find somewhere else to live.

Like everyone we know who lives in San Francisco, we have thought — we think every day — about moving away. And like everyone, we hope to stay. My husband works for the City of San Francisco and I work for UC Berkeley, which seem like important local institutions. Neither of us grew up in San Francisco, but four generations of my foremothers were born in California (although if you’re white, which I am, that just means your people were in on the ground floor of some original displacement). Even so, my baby, now a year old, has a grandmother and a great-grandmother a short train ride away. Why should we be the ones to move?, we think, just like everyone else. Self-righteous defiance is never a good feeling; add to it the knowledge of complicity in a fundamentally unequal society, evident in every public housing-adjacent Victorian flipped and sold for enormous profit, every gingerly-worded spiel from a realtor about Oakland neighborhoods, every crowd of white house-gawkers on streets where black people have lived for a century.

Our situation is not remotely dire — it is merely one of recalibration. Most Americans our age are letting go of the cherished, unexamined assumption that they will be able to give their own children the comforts — or preferably more comforts than — they themselves had. These are comforts captured in movies and books from the very recent past: I idly remember the movie Home Alone and my first thought is How the fuck did they afford that place? (Don’t get me started on Full House.) In The Sportswriter, the first of Richard Ford’s Bascombe novels, Frank is a writer and his wife doesn’t work; they have three small children and live in a house that they own:

Our situation is not remotely dire — it is merely one of recalibration. Most Americans our age are letting go of the cherished, unexamined assumption that they will be able to give their own children the comforts — or preferably more comforts than — they themselves had. These are comforts captured in movies and books from the very recent past: I idly remember the movie Home Alone and my first thought is How the fuck did they afford that place? (Don’t get me started on Full House.) In The Sportswriter, the first of Richard Ford’s Bascombe novels, Frank is a writer and his wife doesn’t work; they have three small children and live in a house that they own:

We went on vacations…We paid bills, shopped, went to movies, bought cars and cameras and insurance, cooked out, went to cocktail parties, visited schools, and romanced each other in the sweet, cagey way of adults.

Yesterday’s magazine writer is today’s millionaire. As one of Meghan Daum’s friends lamented in her book: “…boomers live in mansions they bought for $67 in the early 1980s and we’re destined to live our lives paying rent to guys who wear tinted eyeglasses and Members Only jackets.”

The beloved children’s writer Beverly Cleary enshrined a much humbler vision of middle-class life on Klickitat street in Portland, Ore.; her characters Ramona and Beezus Quimby live in a modest but pleasant house with parents who haven’t finished college and who have a series of jobs that couldn’t comfortably support life in most urban areas today: shop clerk, office worker for a moving company, medical receptionist. Beezus and Ramona live in Portland, but many of Cleary’s less-well-known books — Mitch and Amy, Sister of the Bride, Fifteen — describe middle-class families giving their children good lives in nice Bay Area dwellings, the air scented with eucalyptus. Cleary herself was a California transplant; she attended UC Berkeley and lived around the Bay with her husband Clarence. In 1948, they bought a house in the Berkeley hills. She was a librarian-turned-writer and he was a contracts analyst at the university, a job which today commands a respectable annual salary between $49,000 and $65,000. But I’ve seen a two-bedroom, 792-foot-square-foot house in the same area list for over a million dollars.

The beloved children’s writer Beverly Cleary enshrined a much humbler vision of middle-class life on Klickitat street in Portland, Ore.; her characters Ramona and Beezus Quimby live in a modest but pleasant house with parents who haven’t finished college and who have a series of jobs that couldn’t comfortably support life in most urban areas today: shop clerk, office worker for a moving company, medical receptionist. Beezus and Ramona live in Portland, but many of Cleary’s less-well-known books — Mitch and Amy, Sister of the Bride, Fifteen — describe middle-class families giving their children good lives in nice Bay Area dwellings, the air scented with eucalyptus. Cleary herself was a California transplant; she attended UC Berkeley and lived around the Bay with her husband Clarence. In 1948, they bought a house in the Berkeley hills. She was a librarian-turned-writer and he was a contracts analyst at the university, a job which today commands a respectable annual salary between $49,000 and $65,000. But I’ve seen a two-bedroom, 792-foot-square-foot house in the same area list for over a million dollars.

After the news that our local wreck, the “contractor’s special,” sold for $200,000 over asking, I began to cling desperately to the rental we were in. Heavily pregnant, I lumbered around the place with loving purpose, directing my husband in the hanging of new curtains, adjusting the crib in the baby’s corner of our room, filling our closet with elaborate stacking drawers. I moved so far from my original position about the house’s size that I even schemed to buy it from our landlady, until it became clear that we couldn’t afford it at its current valuation.

There are spiritual implications for a person’s dwelling. As Frank Bascombe puts it, thinking about this anxious clients, the home they buy will

…partly determine what they’ll be worrying about but don’t yet know, what consoling window views they’ll be taking (or not), where they’ll have bitter arguments and make love, where and under what conditions they’ll feel trapped by life or safe from the storm.

I understood that the manic bursts of scrubbing and fussing and considering pillows that afflicted me during pregnancy were something called nesting, and were a known biological phenomenon. I was not expecting this mania to stick around. But, a lifetime slob, I now find myself in the kitchen making the practiced gestures of somebody else’s mother — wiping away a piece of wet fuzz or straightening a placemat, putting all of the puzzles together and stacking them in a corner at night. Some of this, I’m sure, is garden-variety patriarchy stuff that is bound to pop up after millennia of foremothers tidying up. But I am surprised by the feeling of total, whole-body well-being that comes over me when I’m in my special corner of the couch surveying the clean living room. And by the way this feeling seems obscurely connected to the panic-making wave of love that overcomes me at odd moments as I watch my daughter play on the living room rug (a rug, as it happens, that I coveted and lobbied and hoarded for and finally bought when it went on sale).

“Home is so sad,” wrote Philip Larkin, but he probably never held a baby on a soft rug on a sunny day in a nice room that he made for her. I know it’s very irritating to hear people describe the ways that having a child changed them, but this is one that really caught me off-balance: I’ve become house-proud. I think of all the other house-proud women leaving their special corners and favorite rugs in Syria and Iraq, holding close their precious children and stepping into the waves.

When we consider the people in camps, the people in the frigid sea off of Lesvos and Ayvalık, if we believe that all humans are brothers and sisters, none of us deserve stability in the broad moral sense. Aim the telescope back at America, where we have codified a national myth that if you have a good job you’ll have a nice place to live for as long as you want to live there. Articles like this one show how untrue that myth has been for vast swathes of our citizenry, and for how long it has been untrue. If you are a narcissist who was raised in a religious tradition you might feel that your own, absurdly mild housing anxiety is the opening sally of an absent-minded deity who has finally put down his paperback and noticed that things seem off-kilter. I know that I don’t deserve to have a nice place to live for as long as I want to live there, apart from the idea that all human beings deserve this. But that doesn’t mean I don’t — the we all don’t — want it real bad.

The “contractor’s special” went on the market again for $850,000, and sold for $1.1 million a couple of months ago. From the outside it’s still one of the ugliest houses in San Francisco. What ended up happening to us is the thing that you find happened to any San Franciscan who isn’t rich but has a good living situation: we got unreasonably lucky. When our baby was three months old, our next-door neighbors did the almost impossible and managed to buy a short-sale house with a special loan from the city. Our landlady, who also owns their place and is a deeply decent person, let us move in without significantly raising the rent. Deus ex machina. The people, meanwhile, who moved into our old place had been evicted from their decade-plus rental in another neighborhood; they are in their 50s or 60s and clearly paying more for less space than they used to have. Last week a woman strolling up and down our block told me she had grown up a few houses over, but that she couldn’t afford to live in the city anymore. “It should be me in there,” she said, gesturing at her old house. And begrudgingly corrected herself: “I wish it were me.”

We are favored, for now, in San Francisco’s zero-sum housing game. We dearly love our new place, even though it has wall-to-wall carpeting and it isn’t ours. We still don’t have rent control, but we hope for the best. We walk to the BART; we walk to the daycare, where our baby learns Cantonese words from her fellow sixth-generation Californians. What will the gods exact from us, for our good fortune? The twin specters of death and heirs loom all around. But death and heirs are waiting in the wings, I suppose, whether you rent or own.