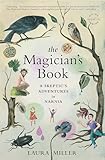

Early in The Magician’s Book: A Skeptic’s Adventures in Narnia, Laura Miller talks about what it feels like to fall in love with a book — and to want to keep it all to yourself. “Discovering Narnia felt like a breathtaking expansion of the boundaries of my world,” she writes, “yet it was also an intensely private event.” Throughout her bibliomemoir, Miller talks to dozens of other Narnia lovers, including Neil Gaiman, Susanna Clarke, and Jonathan Franzen. But perhaps more importantly, she talks to the teacher who introduced her to C.S. Lewis’s fantasy series. “You were so excited you couldn’t talk about it. I tried, but you sort of clammed up,” Wilanne Belden tells her. “I knew how important it was to you, but I think you thought that if you talked about it, it would get away.”

Among all the people she interviewed for The Magician’s Book, Miller describes the few friends who remembered an eagerness to discuss and share Narnia — or Middle Earth — as exceptions to the rule. Most people described childhoods in which they selfishly guarded their most beloved books, the memories of falling into fictional worlds wrapped up with memories of deep solitude. It’s a sentiment I’ve been encountering with some regularity recently, talking to friends and colleagues and a number of authors, notably ones who write books for younger readers — people who arguably have a more acute recollection of the formative power of books at that age.

Among all the people she interviewed for The Magician’s Book, Miller describes the few friends who remembered an eagerness to discuss and share Narnia — or Middle Earth — as exceptions to the rule. Most people described childhoods in which they selfishly guarded their most beloved books, the memories of falling into fictional worlds wrapped up with memories of deep solitude. It’s a sentiment I’ve been encountering with some regularity recently, talking to friends and colleagues and a number of authors, notably ones who write books for younger readers — people who arguably have a more acute recollection of the formative power of books at that age.

When I cast back to my own childhood, I don’t remember a burning desire to share the books I loved with other people — but I don’t remember worrying that the magic would slip away if I tried to share any of that, either. I had no trouble tumbling head-first into fictional worlds, and I would linger there, writing the sort of un-networked fanfiction that lots of children dabble in. In adolescence, I came online, and saw that millions of other people were eager to talk about books they loved (and to write networked fanfiction, the kind that I study and write about, that’s meant to be shared, texts talking to texts). I lurked for years, sitting in a paradoxical place where I felt like I was a part of an enormous conversation about my favorite books — but I never said a word.

Is reading an inherently solitary experience? For many of us, our earliest encounters with books probably weren’t solitary at all: if we were lucky, adults read to us until we were skilled enough to take matters into our own hands. If late childhood is the time of unfettered solitary reading, it’s in adolescence when we learn to read together again, critically now, in classrooms as well as outside them. If we keep reading into adulthood, our habits are mostly dictated by preference: if we choose to share the experience of a good book, it’s with a friend or two, or a book club, or 1,000 other people in an online community. Sometimes it’s the book itself that dictates how much or little to share; more often, it’s a reader’s inclination. And sometimes readers are like my paradoxical lurking self: they want to experience something very private together.

In my capacity as a fandom journalist, I’ve spent the past few years attending fan conventions of various shapes and sizes, from the bombast of San Diego Comic-Con to the organic inclusiveness of NineWorlds in London. But I love books more than most of the pop culture on display at these cons, so I prefer gatherings that have books at the heart, from YALC at London Film and Comic-Con to Book Expo America’s consumer-facing BookCon to GeekyCon, which began years back as LeakyCon, named after the Harry Potter fan hub “The Leaky Cauldron.” These events are usually a mix of author panels and signings, and the publishers come out — with books to sell — in full force. But there’s something notable about the crowds at these bookish conventions, and it’s something I’ve puzzled over: they’re mostly young, mostly female, and while you spot plenty of groups geeking out over books, you see a fair number of readers on their own — actively reading. Tucked up in the corners of convention centers, these cons are full of people skipping out on all the programming to read, a curious sort of collective solitude on display.

Last weekend I trekked to the far, far west side of Manhattan to attend the inaugural Book Riot Live. It was the first major event for Riot New Media, the group that owns the popular bookish site Book Riot, and it brought in about 50 speakers, two dozen vendors, and more than 1,100 guests over the course of the weekend. “Book Riot Live came out of our desire to get the community together in real life,” Riot New Media’s events and programming director, Jenn Northington, told me. “Making sure that [it] reflected and celebrated our community was our number one concern. It influenced everything — programming, the layout, the vendors we invited, everything…What are they interested in, which authors have we seen people get the most excited about, what topics have created the most dynamic conversations.”

It was a weekend characterized by dynamic conversations: on the various stages, there were live podcast recordings, panels on bookish topics ranging from specific craft-related challenges to issues of inclusion and diversity in publishing at large, and authors like Margaret Atwood and Laurie Halse Anderson to get the crowds riled up (they were talking about sexism and censorship, respectively). Thankfully for me, it had a far more fannish feel than, say, the programming at BEA, where panelists (in my experience, at least) often seem like they’re confused by things they’re observing rather than speaking with authority about book fandom. These panels were populated by actual fans of books — and that was reflected pretty visibly in the audience, too.

But one of the most interesting things at Book Riot Live was up front, near a set of floor to ceiling windows that offered up a great view of the tourists approaching the Intrepid, moored in the Hudson. There were a few large, circular tables, and beside them, a circle of little beanbag armchairs, all occupied by people reading silently — people sitting alone together. “I can’t remember exactly when we had this idea, but it was part of the planning from very early on!” Northington told me when I asked her about it. “I cannot tell you how many times at other conferences and conventions I’ve heard people say ‘I wish there was a Quiet Room’ or ‘I wish there was somewhere I could just go and sit and look at all these books I now have.’ We definitely all wish for that on staff! So it was a no-brainer to set up a space for it.”

Whenever I took a seat in the quiet area, at a table or squashed down on one of the beanbags, I was struck by what a thoughtful space it was. If you took out a book in any random public space, you’d have to work to block out the rest of the world. (When I forget my noise-cancelling headphones, I often feel like I’m doing battle with the rest of the world when I’m trying to read or write — especially if the book’s a drag.) At Book Riot Live, that exchange was seamless, and silently negotiated: people seemed to sense exactly who wanted to strike up a conversation with another book-loving stranger — and who just wanted to be alone with a book they loved.

Northington and her colleagues seem to have a deep understanding of the duality at play here. “We are all big-mouths about books, all the time,” she told me. “Book Riot as a site came out of the litblogger community and was originally conceived as a blogger collective, and that’s a self-selecting group. You don’t start a blog unless you’re dying to talk with other people about what you’re reading. But I can completely understand folks who just want to sit with the work. There are stories that become so intensely personal that talking about them in public can make you feel mentally naked, and very vulnerable. There have certainly been times I’ve had to process my reaction to a book for a while before I could talk to anyone about it.”

When I write about book fandom, especially for an audience that’s less broadly fannish and more broadly bookish, I often sense a tension from people who can’t imagine reading being a communal experience. For them, it isn’t. I see that same tension with every book start-up that emerges and eventually folds: so many of them have aimed to socially network the reading experiences of the types of readers who just want to be left alone with their books. What a lot of these attempts fail to acknowledge is the people who want to read communally don’t need a new app to do it. If you want to talk about books with other people, you’ll find your spaces online, ones where you get to dictate how — and how much — you share what you’re reading.

These spaces are plentiful in the digital world; perhaps in the future, they’ll be just as easy to find in the analog world as well. If digital technologies have made our private spaces more public, maybe we need more squashy beanbags to make our public spaces a little more private. Maybe we’ll regularly be able to say, “I’m going to go out — and curl up with a good book.”

Image Credit: Flickr/Erin Kelly.