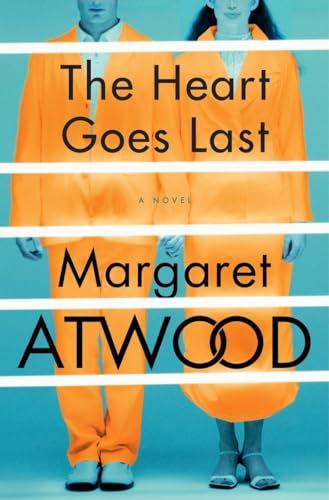

The Heart Goes Last — Margaret Atwood’s first standalone novel since The Blind Assassin, which won the Man Booker in 2000 — is a novel that teeters on the fine edge between comedy and horror. The writing is full of Atwood’s wry humor, but the dystopian world in which the characters live, whether they are a sleeping in a car and fleeing thugs or under surveillance in a tightly controlled community, is an alternate world that is full of horror.

The novel tells the story of Stan and Charmaine. After a great financial crash, their home is repossessed, their credit is frozen, and they are left to eek out a meager life living in their cramped Honda for shelter. Stan sleeps in the driver’s seat so they can flee quickly during the night if need be. With only Charmaine’s money from a bartending job, they dumpster dive, eat day old doughnuts, and have no viable prospects for their future. When Charmaine sees an ad on TV for Consilience, a suburban utopia and a ‘social experiment,’ she signs them up to take a look. Participants are given a home of their own in exchange for going to prison every other month.

The idea behind Consilience is that a full prison creates full employment and all prosper. While Charmaine and Stan do their month in jail, they swap places with an alternate couple who live their life, drive their scooters, and sleep in their bed until the month is up and they trade places again. In a set up that recalls a Midsummer’s Night Dream-like mix up, unknown to each other both Stan and Charmaine have chance encounters with their alternates. Confusion, obsession, and mistrust turn into revelations about the truth about Consilience.

The more I read, the more I questioned whether I could describe the community of Consilience and the chaos outside its gates as taking place in an alternate world. So much of what happens in this novel, from foreclosed houses to private prisons, is already part of our world. The world of The Heart Goes Last feels more like a twisted version of our current reality. Only small changes would be needed to make it all ‘true.’ Just as Charmaine and Stan’s lives contort when they seek out their alternates, utopian turns dystopian and comedy bends into horror with, as Atwood says, “one small turn of the wrench.”

I interviewed Atwood over the phone from her hotel room in New York. We spoke about not having sex with furniture, Pepper the greeting robot, themes in Victorian literature, and quotas in private prisons.

The Millions: The Heart Goes Last has your trademark humor, but the circumstances that Stan and Charmaine find themselves in are horrifying.

Margaret Atwood: A lot of things are funny to those watching them, but not to the person undergoing them. The person who slips on the banana peel doesn’t think it’s funny as a rule.

TM: Charmaine says near the beginning of the book that, “comedy is so cold and heartless, it makes fun of people’s sadness.”

MA: It does, unfortunately. Sometimes people make fun of themselves, but if you dig down there’s a bit of that too. On the other hand, where would we be if we couldn’t laugh? I think they’ve always been joined at the hip.

TM: At the beginning of the novel, you quote Ovid, William Shakespeare, and a blog post by writer Adam Frucci[1] — who sets out to test an ottoman with a fake vagina. I have to ask: Did you have sex with furniture to research this novel?

MA: I think that piece of furniture is intended only for men?

TM: Frucci warned that it was, “no Kleenex clean up, my friends.” Actually, what he endured to test the ottoman is a good example of something that is funny for the reader, but not so for the person going through the experience.

MA: One of the headlines of that post is “I did this so you don’t have to.” Frucci has probably woken to find himself strangely famous. A lot of people are reading that blog post.

The other thing that has to trouble your mind is — who had this idea for this piece of furniture? And would you have this in your living room? I have many questions.

TM: Maybe you’ve given the ottoman maker a little sales bump?

MA: I have a feeling that a piece of furniture with a sex thing built into it came and went fairly swiftly. If that blog post was written in 2009, the furniture has fairly quickly been superseded by the advances in robotics.

Do you know about Pepper the robot? Pepper is not a sex robot. In fact, Pepper comes with instructions that say explicitly that you are not supposed to use it for sex, though I don’t know how you could.

Pepper is a greeting robot, like one that Stan, the main character in The Heart Goes Last, is working on before he gets fired at Dimple Robotics. Except that Stan’s is a grocery bagging robot. It is supposed to smile at you.

Pepper is supposed to be able to read your emotions. They were installing Pepper as a greeting robot in Japan where greeting is a social custom. And then they put him/her on for private sale and he/she sold out very quickly. Apparently we want someone who can read our emotions.

TM: At Dimple Robotics, Stan’s job, before he looses it, was working on the empathy module of his robot.

MA: Personally, I don’t want someone who can read my emotions, because then you can’t dissimulate, can you? If somebody asks if you are having a nice day and you say yes, but you’re actually not…it spoils your act.

TM: It’s the white lies that get us through.

MA: I’m afraid that’s correct. They do. “That’s a lovely dress! You look wonderful!”

TM: The novel is filled with this kind of joke — your humor is always close to hand. I love a line on writing from Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be?: “You have to know where the funny is, and if you know where the funny is, you know everything.” Do you agree?

TM: The novel is filled with this kind of joke — your humor is always close to hand. I love a line on writing from Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be?: “You have to know where the funny is, and if you know where the funny is, you know everything.” Do you agree?

MA: No, but it’s a good hint. You don’t know everything if you know that, but you know some things. It’s true in a negative way. If something is unintentionally funny, you ought to know. If you intended it to be very serious and dramatic, but actually it’s funny, then you are in trouble.

There is a wonderful book called The Stuffed Owl. It’s an anthology of good, but bad, verse. It’s well worth reading. It is full of writers who were aiming for the heights and tripped on the banana peel.

There is a wonderful book called The Stuffed Owl. It’s an anthology of good, but bad, verse. It’s well worth reading. It is full of writers who were aiming for the heights and tripped on the banana peel.

TM: As I was reading The Heart Goes Last, I kept thinking back to Survival, your thematic guide to Canadian literature that was published in 1972. In it you said: “I read then primarily to be entertained.” Do you still?

MA: Go back to what the ancients used to say, that art should entertain and instruct. They didn’t say to what degree. If it doesn’t entertain, and by entertain I don’t mean just frivolous, I mean engage your attention and keep you going. If that doesn’t happen, you’re not going to turn the page. So there has to be something engaging enough to keep you reading.

That is why first chapters are so important. If you can’t get the reader through the first chapter, they are never going to get to your pithy piece of wisdom on page 85.

On the other hand, if there is nothing serious in it, you may be entertained on a superficial level and it’s a one time read. Or it’s what we call a “beach read.” Or what I sometimes call a “hotel room drawer read.” I leave them there for others to enjoy. I did that in Hong Kong once and they were so screamingly honest that they collected the books and mailed them back to me. I thought that was so sweet.

TM: The Heart Goes Last is about characters who give up their freedom for comfort. When Stan and Charmaine tour Consilience for the first time they both feel reason to worry about how it runs. However, after experiencing the discomfort and fright of life in a car, they opt for comfort, “the bath towels clinched the deal.”

MA: Yes. It’s also about how circumstances cause people to do things that they would otherwise not do. That is a human universal truth. Stan and Charmaine give up their freedom, but of what does their freedom consist? They don’t have a lot of money, they are living in their car, they are subject to every thug and criminal that stumbles across them, so that is maybe “freedom,” but of a very limited kind.

TM: Can we expect a scared or thirsty human to make good decisions?

MA: You can’t. Self-preservation kicks in. A person will make the decision that you think gives him or her the best chance of getting through.

TM: In that way, is The Heart Goes Last a survival story?

MA: A lot of people lived that, or something close to it, when the 2008 crash happened. They were thrown out onto their front lawn or living in their cars. That is ongoing.

There’s a movie that just came out that I must go and see called 99 Homes — it’s the story of a man who evicts people from their houses because they couldn’t pay their mortgages. As I said, the situation is ongoing.

I was listening to the radio in London, England, and there was a show about people who had moved back into their parents’ houses, or parents who have had their kids move back in, because they could not afford to either rent or buy in London. It was too expensive.

TM: The set up of your novel felt so real.

MA: It is real.

TM: But it’s not necessarily your reality. David Mitchell wrote about how he imagines the far past or the far future, that to get in the right mindset he thinks about the things that the characters might take for granted in life.

MA: We did a lot of car travel when I was a child. We also did a lot of camping out. So that wasn’t under duress, but I know what it’s like to sleep in a car.

TM: There are other parts of the book that could be taken as speculative fiction, but aren’t, like private prisons.

MA: There are private prisons in the U.S. The Atlantic just did a huge piece on this. There is nothing in the U.S. constitution that says you can’t make people do enforced labor if they are convicted criminals.

There’s a history of that kind of prison as enterprise. The Australian penal colony was one of them. They would send people to work off their sentence. Someone was making money out of it.

TM: I also read that in Arizona there are three private prisons that require 100 percent inmate occupancy.

MA: You have to keep them full to make them profitable and that is a recipe for creating more prisoners.

TM: In 2008, when you published Payback, a book of non-fiction about the nature of debt, it almost felt like the world of finance had collapsed at your feet. The timing was quite something. Tell me about your crystal ball?

TM: In 2008, when you published Payback, a book of non-fiction about the nature of debt, it almost felt like the world of finance had collapsed at your feet. The timing was quite something. Tell me about your crystal ball?

MA: I don’t actually have a crystal ball, but I do read advertisements when I’m sitting on the subway. I was seeing a lot of them that said “let us help you get out of debt.” I thought, boy, if there are all these enterprises doing that, there must be an awful lot of people in debt.

The other thing is that, if you are a student of Victorian literature, as once I was, debt is a big theme. Not only with Dickens, but a number of other writers as well. So is the prison system.

TM: In Survival you wrote, “Literature is not only a mirror; it is also a map.” Can The Heart Goes Last be read as a map?

MA: Maybe a map, but also a door. Open the door and what’s inside? Stan and Charmaine are in a planned prison system, a for-profit enterprise. What they don’t know when they go in is how the enterprise is making its money. The thing to ask about private prisons is who is making the profit? And how much are they making. Maybe it’s time to rethink. What should we have instead?

__

[1] I contacted Adam Frucci, author of “I Had Sex with Furniture: The Shameful (NSFW) Fleshlight Motion Review,” to comment about the honor of becoming an Atwood epigraph: “I didn’t really believe it at first — Ovid, Shakespeare, and my goofy blog post from 2009. I can’t say that of all of the things I’ve ever written that this is the one I want people to remember and attach to my name, but what can you do? All I can really do is be honored and assume that Margaret Atwood is a huge fan of all of my work and looks to me for inspiration all the time. That’s about accurate, right?”