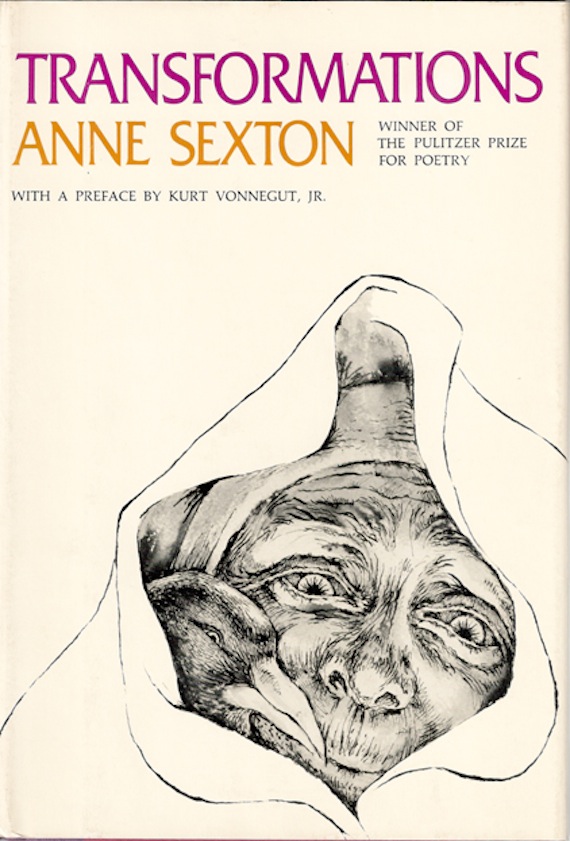

Transformations, Anne Sexton’s 1971 collection of poems, is a portal. The front cover, our entrance, is a drawing of a peasant and a raven, taken from the Brothers Grimm tale “The Little Peasant.” During a storm, a traveling peasant seeks shelter at a mill. The miller’s wife is home alone, and she gives the peasant food, drink, and apparently much more. The miller returns home, and his wife is frightened that he will discover her infidelity. The peasant diverts the husband’s wrath by presenting a raven wrapped in cowhide as a soothsayer.

The peasant is a trickster, one transformed. His wizened face is the proper entrance to this experience. Our exit is of the now-defunct, full-page author photograph variety: Anne Sexton sitting on a screened-in porch. She wears a white dress and sits in a wicker chair, holding a half-smoked cigarette. Sexton is curator, narrator; she who transforms. She opens the collection with a frame: “The speaker in this case / is a middle-aged witch, me.” She implores her readers to “draw near,” and asks, even at 56 years old, “Do you remember when you / were read to as a child?” She laments our adult loss of wonder and terror. She offers this book as a poisonous antidote.

Transformations feels so absolutely a product of the early ’70s. Poems from the book appeared in Cosmopolitan and Playboy. The experience of reading Sexton’s poems mirrors a child finding and scouring through Grimm’s tales in a wood-paneled basement during that decade. Huddled in a dark corner within a brightly-lit suburb, she sees another, older, darker world — while surrounded by board games, extension cords, and Christmas decorations.

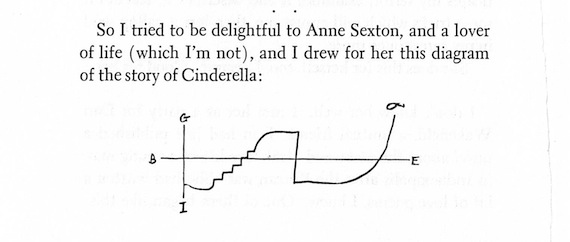

Sexton dedicated the book to her daughter Linda, “who reads Hesse and drinks clam chowder.” It is the only book of poetry that contains a preface by Kurt Vonnegut. Vonnegut met Sexton at a party, and drew her a story diagram for Cinderella.

Sexton was already retelling the Grimm fairy tales, a manuscript that would become Transformations. Vonnegut has high praise for Sexton: “she domesticates my terror, examines it and describes it, teaches it some tricks which will amuse me, then lets it gallop wild in my forest once more.” “How do I explain these poems?,” he wonders. “Not at all.” Vonnegut’s preface reads like the gasp of an admirer, who seeks not to explain but to bear witness.

Sexton injects the modern world into Grimm’s fairy tales, but does so by inserting mundane references and contemporary mood. The result is poems with the architecture of archetype but modern anxiety. She inserts prefatory poems before the tales proper. Some prefaces, as for “The White Snake,” connect narrator to transformation: “I knew that the voice / of the spirits had been let in–/ as intense as an epileptic aura–/and that no longer would I sing / alone.” Others, as for “Rumpelstiltskin,” connect past to present: “He speaks up as tiny as an earphone / with Truman’s asexual voice.”

In Sexton’s re-telling of that tale, a miller says his daughter could spin gold from straw. The land’s king locks her in a room, where “she would die like a criminal…Poor thing. / To die and never see Brooklyn.” The modern creeps into “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” with the virgin’s “cheeks as fragile as cigarette paper.” Or when the queen “dressed herself in rags / and went out like a peddler to trap Snow White,” and wraps lacing “as tight as an Ace bandage” around Snow White. The marriage of legend with Limoges is quite surreal.

Sexton also documents the secret transformations that surround us. From “Red Riding Hood:”

The suburban matron,

proper in the supermarket,

list in hand so she won’t suddenly fly,

buying her Duz and Chuck Wagon dog food,

meanwhile ascending from earth,

letting her stomach fill up with helium,

letting her arms go loose as kite tails,

getting ready to meet her lover

a mile down Apple Crest Road

in the Congregational Church parking lot.

Other than the cleverness of her updates, Sexton delivers stirring lines. “Rapunzel” begins “A woman / who loves a woman / is forever young.” In another tale, the narrator notes “The unusual needs to be commented upon.” I have always thought of Anne Sexton in tandem with Sylvia Plath for this exact line. Sexton and Plath are often coupled because of their suicides, but they are connected in poetry through their spinning of the unusual. Consider Plath’s “Sow,” her ode to a “Mire-smirched, blowzy” marvel that had been “impounded from public stare, / Prize ribbon and pig show.” From “Pheasant:” “It startles me still, / the jut of that odd, dark head, pacing / through the uncut grass on the elm’s hill.” Sexton’s poetry feels like it has consistently more thorns than Plath’s, whose movement toward myth felt more folk than dark.

I also return to Transformations because it is a God-soaked book. There are small touches, as when Hansel and Gretel’s mother “gave them / each a hunk of bread / like a page out of the Bible,” as well as an overall tone that reflects the detritus of Sexton’s Protestant upbringing. Her final book was the posthumously published The Awful Rowing Toward God. An epigraph to her earlier poem “The Starry Night,” is an excerpt from Van Gogh’s letter to his brother: “That does not keep me from having a terrible need of — shall I say the word — religion. Then I go out at night to paint the stars.”

I also return to Transformations because it is a God-soaked book. There are small touches, as when Hansel and Gretel’s mother “gave them / each a hunk of bread / like a page out of the Bible,” as well as an overall tone that reflects the detritus of Sexton’s Protestant upbringing. Her final book was the posthumously published The Awful Rowing Toward God. An epigraph to her earlier poem “The Starry Night,” is an excerpt from Van Gogh’s letter to his brother: “That does not keep me from having a terrible need of — shall I say the word — religion. Then I go out at night to paint the stars.”

Sexton corresponded for years with Brother Dennis Farrell, a Benedictine monk from California. Sexton’s letters are whimsical. She “wishes you’d convert my doubt to belief” but “knows you won’t cuz it ain’t that easy.” She had been reading The Way of the Cross: “I like it. I see it twice, through my eyes and through yours…I think of Mary…I wonder what she felt…What was she wearing? How long was her labor? Things like that…it is the poet in me that wants to know. The book is giving me a new insight and love and understanding of Jesus and of his humanity.” She even sent the monk a draft of a poem that she “dared not publish” for she wonders “if it insults Christ…for I will change the last two lines if they do not work.”

Farrell apparently fell in love with Sexton, decided to leave his monastery, and hoped to see her. Sexton responded in a long, recursive, passionate missive, but her rejoinder is firm: “Our letters…no matter how direct and human they may seem to you are not to be compared to a direct relationship.” In an earlier letter she indirectly warned that “people think poets are in touch with some mystical power and they endow us with qualities we do not possess and love us for words that we only wrote for ambition and not for love.” The monk had forgotten a poet’s letters of love are poems, not truth.

In the notes to Anne Sexton: A Self-Portrait in Letters, Sexton’s daughter and Lois Ames explain that following the “gradual dissolution of her deepest relationships,” when Sexton’s “friends provided less and less support, she turned to God for comfort.” She would “read Xeroxed weekly sermons from a church in Dedham” and became friends with the pastor. Sexton was not a traditional convert. Her God was a personal revision of the Protestant God she had found so wanting.

In the notes to Anne Sexton: A Self-Portrait in Letters, Sexton’s daughter and Lois Ames explain that following the “gradual dissolution of her deepest relationships,” when Sexton’s “friends provided less and less support, she turned to God for comfort.” She would “read Xeroxed weekly sermons from a church in Dedham” and became friends with the pastor. Sexton was not a traditional convert. Her God was a personal revision of the Protestant God she had found so wanting.

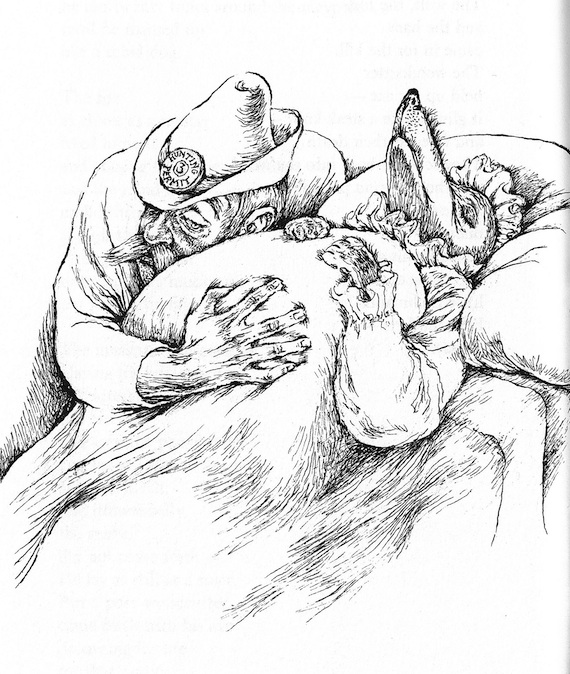

That revision is reflected in the tone within Transformations. Vernon Young, in one of the first reviews of the book, called the poems “occasionally vulgar, often brilliant, nearly always hilarious,” and the complementing drawings “importunate and macabre; Gothic and placental.” Barbara Swan’s work is the perfect twin to Sexton:

I return to Transformations to be snatched back to the past. The most disturbing story-memory from my own childhood is the scene in Rumpelstiltskin when the queen’s messenger saw a fire burning in front of a little house: “Around that fire a ridiculous little man / was leaping on one leg and singing: / Today I bake. / Tomorrow I brew my beer. / The next day the queen’s only child will be mine.” I think it was the proximity of mundane life and legend, of joy and horror. Sexton inhales the Brothers Grimm and exhales something darker and newer, all while sitting in a white dress on a white wicker chair, smirking at us.