There’ll always be a place for the sad sack in fiction, heroes of topsy-turvy Bildungsromans who regress or stall rather than develop. Call them protagonists of the comic or the failed coming-of-age tale, which has its obvious forbears in a work like Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy but also in the merciless irony of Gustave Flaubert’s Sentimental Education. In the classic version of the Bildungsroman, the hero seeks to define himself in a variety of ways — personally, educationally, professionally, romantically, or creatively if he happens to be an artist. The hero of the comic Bildungsroman tends to resist, or fail to achieve, these definitional ends. It is full of outsized characters who never quite fit into the narrative bounds imposed by the form: “Where will you ever end?” Ignatius Reilly is asked in The Confederacy of Dunces, a question that homes in on the particularly expansive comic spirit that refuses to conform or be confined to established conventions.

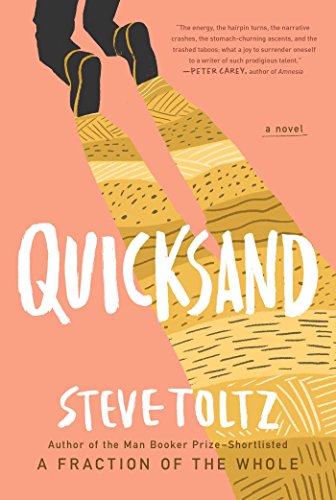

The same question could be put to Aldo Benjamin, who at one point in Steve Toltz’s Quicksand pleads, “My kingdom for a terminus!” Aldo is one of the two failures in the Australian novelist’s latest, an eminently successful novel about “the pilgrim’s frustrating lack of progress.” There’s a touch of Reilly in Aldo, but given Aldo’s mixture of libidinousness, thanatos, and linguistic virtuosity, Philip Roth’s priapic puppeteer Mickey Sabbath comes to mind as a closer precursor. Like all good comic characters, Aldo, a hapless entrepreneur, proves difficult to contain or circumscribe, not only because of the profusion of his misadventures but because he fancies himself as a real-life Tithonus, a “poor deathless, imperishable creature.” After a string of failed suicides — “suicide’s block” he calls it — Aldo thinks he has inadvertently caught a case of immortality: “In the face of forever, the contours of one’s life slacken and become not just poorly defined, but permanently resistant to definition.”

The same question could be put to Aldo Benjamin, who at one point in Steve Toltz’s Quicksand pleads, “My kingdom for a terminus!” Aldo is one of the two failures in the Australian novelist’s latest, an eminently successful novel about “the pilgrim’s frustrating lack of progress.” There’s a touch of Reilly in Aldo, but given Aldo’s mixture of libidinousness, thanatos, and linguistic virtuosity, Philip Roth’s priapic puppeteer Mickey Sabbath comes to mind as a closer precursor. Like all good comic characters, Aldo, a hapless entrepreneur, proves difficult to contain or circumscribe, not only because of the profusion of his misadventures but because he fancies himself as a real-life Tithonus, a “poor deathless, imperishable creature.” After a string of failed suicides — “suicide’s block” he calls it — Aldo thinks he has inadvertently caught a case of immortality: “In the face of forever, the contours of one’s life slacken and become not just poorly defined, but permanently resistant to definition.”

This indefinition proves a challenge for his friend Liam, an incompetent policeman — “I hit the siren. It startled me, as usual” — and failed novelist who is writing a book about him. Liam, noting that “[Aldo’s] existence needed room” and that “[h]e can’t tie up all his loose ends because he has an odd number of them,” eventually “[comes] to terms with the fact that there may be no place for every random anecdote and strange story about Aldo in my book.” There is a Whitmanian copiousness to Aldo evidenced in his “absurd” endurance despite and through “forty years of death throes” or in the host of oddly specific phobias he believes he has inherited from his ancestors:

…fear of unraveling rope bridges, fear of causing an avalanche by sneezing, fear of accidentally procreating with a half sister, fear of being shot in the face by a hunter…

Those fears never materialize, but pretty much every other nightmare scenario does as he is shuttled between the prison and the hospital, “two overpopulated hells.” (As he wryly reflects in the midst of one of his ordeals: “Even my subconscious hadn’t the temerity to go so far as to render me paralyzed at a rape trial.”) And yet like Mickey Sabbath, Aldo persists. He is a man of stubborn, and occasionally exhausting, exuberance. “My charm wears off like a local anesthetic,” he concedes after delivering over 140 pages of riveting, mordantly funny, and self-pitying testimony-cum-autobiography — the “short version” — to a beleaguered jury of his peers.

In her review, Lionel Shriver oddly objected to this bravura section by saying its “length strains credulity,” as if courtroom scenes have ever had more than a passing resemblance to realism. (I bet she’s fun to watch The Good Wife with.) Shriver’s critique ignores the novel’s logic of excess, which is established in the very first scene. We first see Aldo, paralyzed from the waist down after his latest accident, drinking at a beachside bar with Liam. Aldo has just come up with one of his idiosyncratic business ideas (e.g., peanut-allergy divining wand), but won’t, or can’t, tell it to Liam without first surrendering to his patience-testing compulsion to riff:

‘You know how we are such optimists that even out Armageddons aren’t final?…You know how people used to want to be rock stars, but now they just want rock stars to play at their birthday parties?…And how when someone’s coping mechanism fails, they just keep using it anyway?…And how businesssapiens are always having power nightmares?…Bad dreams during power naps…You know how when people talk of First World problems they forget to mention Alzheimer’s and dementia?…You know how unrequited love has no real-world applications?…’

These are selections from about 25 “you know” questions, all leading up to the final unveiling of his grand idea: disposable toilets, a fitting invention for a master bullshitter who always finds himself mired in the muck.

The toilet invention provides one clue, and the title a more obvious one, that Quicksand is a story of precipitous decline. Aldo is “not just the falling clown, but the falling clown who other falling clowns fall on,” a man whose life only gets worse after being erroneously charged with rape when he is still a virgin. From then on, he is constantly on trial (another dubious sex crime, murder(s)), in debt, or recovering from suicide attempts, my favorite being the “irreproachably considerate” plan he devises to take sleeping pills and slide himself into a hospital morgue drawer. Liam is slightly discomfited by watching “…a man on a decline from so low a starting point,” but also recognizes the narrative potential: “The only people worth watching are those who have reached rock bottom and bounced off it, because they always bounce off into very strange orbits.”

Aldo may be “a disaster waiting to happen, or a disaster that had just happened, or a disaster that was currently happening.” However, to be singled out for such a fate is its own kind of election. Etymologically, disaster means ill-starred, the empyrean heights determining the trajectory of mortals spiraling downward. Whether he is a modern-day Job or a tragic Greek hero who “locked eyes with the wrong god,” Aldo is a marked man both figuratively and literally. The history of his scars reveals a partial record of his singularly bad luck: “…motorcycles, skinheads, wrong turn, stray billiard ball, ambush by a part of thorns, Molotov cocktail, car antenna, gravel rash, cigar.”

Liam, on the other hand, is unmarked, a man whose own sad tale is eclipsed by that of his brilliantly inauspicious friend. Both lost sisters during adolescence, both have been “dodging success with drone-like precision for nearly two decades,” and both have not been “changed by [their] life-changing experiences.” However, Liam’s quiet desperation is ordinary. When Liam visits Aldo in the hospital after one accident, the latter instantly sees that he has the upper, or rather lower, hand: “His sad face conceded that my downward spiral had crushed his downward spiral. Ah, the pyrrhic victories of old friendships.” They spar with, aid, use, or bore one another during a friendship that is unbreakable despite, or rather because, there remains something “permanently unexpressed between” them.

We learn less and less about Liam as the novel focuses on its “natural subject,” Aldo, so that when Liam is surprised to discover that “people in general think I’m a ridiculous human being,” we do not know enough either to doubt or credit this general view of him. What can’t be called ridiculous is his devotion to Aldo, which is the only thing that keeps him from being a cipher: “You’re a good friend to Aldo,” his former teacher tells him. “That doesn’t make up for what you lack, but it’s not nothing.”

Which isn’t to say that Liam is selfless in his devotion. Like every other artist who comes across Aldo in the novel, he wants to “cannibalize” his life. An inveterate manipulator, Aldo is also an inveterate muse and obliging model; he lets himself be painted and photographed by Liam’s “copious rivals,” a group of bohemians residing in an artist’s colony, even describing his own features to a police sketch artist just for the fun of it. Portraitists circle him like vultures, sensing that his rotten life will provide artistic sustenance. “If they are artists, the truly unfortunate have a wealth of material,” reads an aphorism from Artist Within, Artist Without, Liam’s and Aldo’s vade mecum written by their old high school teacher, Mr. Morell. But what of the “truly unfortunate” supplying the material?

“Unused talent exerts downward pressure on the spirit,” is another of Morell’s nuggets. But squandered talent isn’t quite what drives Aldo, and consequently Liam, down to the level “where things get primordial.” Rather, it’s precisely by deploying his talent, which happens to be for erring, that sends the “King of Unforced Errors” back to the elemental: a barren rocky island at a remove from the society in which he was so incongruous. This tragicomic Bildungsroman fails as it should, spectacularly, its “half-human, half-crustacean” hero devolving in splendid isolation as, back on shore, the world goes calmly on.