1.

My generation of comics fans had a reading list. In grade school, we dug Chris Claremont’s S&M take on the X-Men and reprints of Jack Kirby’s Fantastic Four. When we were 12, we picked up Watchmen, The Dark Knight Returns, and Maus, which dealt with the things 12 year olds think of as adult, like fascism, the military industrial complex, and the Holocaust. In either our senior year of high school or freshman year of college, a friend turned us on to Neil Gaiman, Adrian Tomine’s short stories, and, because it’s fun to see Betty Boop actually have sex, reprints of the Tijuana Bibles. A teaching assistant in a public policy class assigned Joe Sacco’s Palestine, which came with a foreword from Edward Said. There were a few other milestones that brought our interests into the literary mainstream, like Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth, Art Spiegelman’s September 11 New Yorker cover, Fun Home, as well as two novels, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay and The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. We had always kept copies of Eightball next to our issues of Granta. Now the rest of the world does the same.

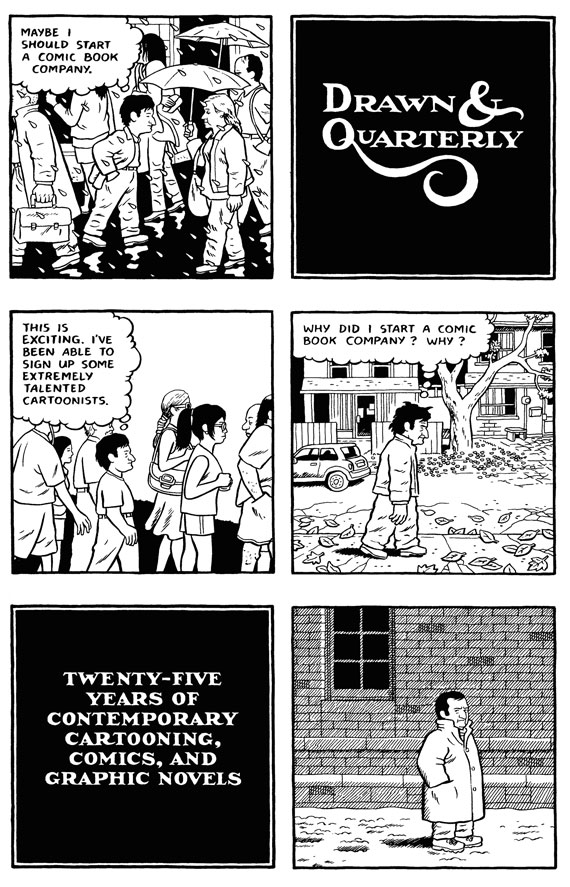

The roster of Drawn and Quarterly — Lynda Barry, Kate Beaton, Chester Brown, Daniel Clowes, Julie Doucet, Jason Lutes, Joe Matt, Joe Sacco, Seth, James Sturm, Jillian Tamaki, Adrian Tomine, and Chris Ware — represents at least a quarter of this high-art, high-literary comics renaissance in the Anglophone world. This summer, the Montreal-based independent comics publisher released a 776-page anthology in celebration of its silver anniversary, Drawn and Quarterly: Twenty-Five Years of Contemporary Cartooning, Comics, and Graphic Novels. It’s a fun book, filled with old and new work by the house’s artists and appreciation essays from scholars, fellow travelers, and novelists.

A publisher’s anthology of its own work will be a hagiography. That’s okay. There are other places for brutal criticism of comics. The mainstream press is learning to develop a more discerning eye towards the form, to not declare every new graphic novel by a semi-famous artist a groundbreaking innovation. The Internet has many take-down podcasts. D&Q’s anthology reads like a high school yearbook, complete with scrapbook-level photographs. The personal essays describe career changes that are more interesting to their authors than to their readers. With that said, the book also provides an important service. The initial phase of the comics renaissance is over, and the publication of this anthology offers an opportunity for understanding what defined D&Q, what we readers were looking for in comics throughout the past 25 years, and what we are looking for now.

2.

Chris Oliveros, the founding editor of D&Q, was smart, industrious, and he had an excellent eye for talent, but there were others before him. Fantagraphics had been around for awhile when Oliveros started his project and it published The Comics Journal, an exuberant and angry forum for comics journalism and criticism. Fantagraphics’s premiere artists, Los Bros. Hernandez, were Latino children of the punk scene. Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly edited RAW. Robert Crumb, Peter Bagge, and Aline Kominsky-Crumb edited Weirdo. Alison Bechdel and Howard Cruse had homes in the niche gay press. There were places for ferocious comics creators who told stories other people weren’t telling, but those spaces were limited. D&Q was a welcome addition to the comics world.

D&Q began in April 1990 as a black-and-white comics anthology. It fit the standard newsstand magazine size at 8.5″ x 11″. It was 32 pages long. It had a glossy cover. In its first issue, Oliveros, who was then in his early-20s, called for higher standards for the comics medium and lamented the “private boys’ club” that characterized the comics industry. The manifesto set a tone for what the company eventually became.

The magazine’s sales were based on the “direct market,” comic-book specialty stores which would buy the magazine on a non-returnable basis. It was the most economically viable option at the time, but it also limited the magazine’s reach. Soon after the first issue of the anthology, Oliveros started publishing single-artist comic books. In a few years, the original anthology magazine went to color and D&Q found inroads into Virgin Megastores (which have disappeared from North America), Tower Records (which are all now gone), and pre-monopoly Amazon. Oliveros started compiling serialized stories in quality paperbacks and hardcovers and published stand-alone graphic novels. Storeowners didn’t quite know what to do with these comics, how to sell them to the people who read literary novels. Peggy Burns, a publicist at DC Comics, came to D&Q in 2003 and in 2005 she negotiated a distribution deal with FSG. The people who published Jonathan Franzen also worked with Adrian Tomine, which was as it should be.

The essays here claim D&Q treats its creators well. D&Q allows its artists to do what they want to do, letting some of them design their books in meticulous detail, determining paper type, size, and printer quality. They are book-makers at heart. D&Q’s artists are good to their fans. They get to know them at conventions and spend a long time inscribing their books with cartoons during signings. The audience who reads this anthology has probably also read the major popular comics histories of the last few years and it knows that a comics publisher that allows creators space for their genius, doesn’t force them to hire a lawyer, and doesn’t populate its staff with misogynists is a special publisher.

3.

No one agrees why D&Q was so good. The testimonials contradict each other.

Jason Lutes, the author of Berlin and Jar of Fools: “They were the kind of comics I was hungry for — taking a cue from the precedent set by Art Spiegelman’s RAW magazine, but stepping out from under the influence of the American underground, which had overshadowed so much of ‘alternative comics’ up to that point.”

Jason Lutes, the author of Berlin and Jar of Fools: “They were the kind of comics I was hungry for — taking a cue from the precedent set by Art Spiegelman’s RAW magazine, but stepping out from under the influence of the American underground, which had overshadowed so much of ‘alternative comics’ up to that point.”

TV on the Radio’s Tunde Adebimpe on his introduction to D&Q: “From then on I only wanted to read and make ‘underground’ comics, watch and make ‘underground’ films, listen to ‘underground’ music, and basically soak up anything that seemed even a little bit subversive.”

Anders Nilsen describes the publisher’s “quiet, understated commitment to quality work.”

It’s not always clear who is on the inside and who is on the outside, what is dangerous and what is just new. Those contradictions define D&Q.

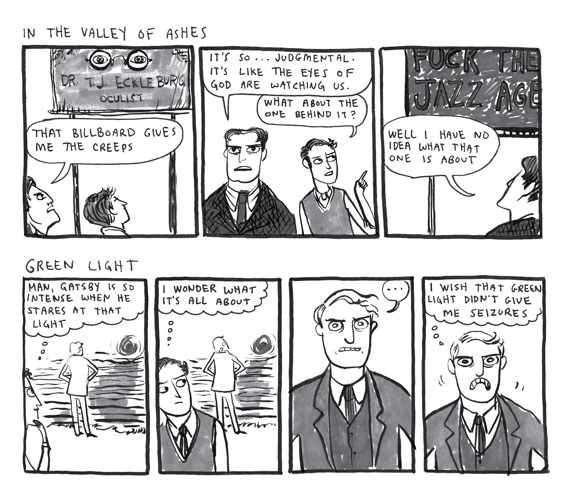

Let’s start with Kate Beaton, who uses the comic-strip format and her naïve style to take down the myths of Western high culture. In her appreciation essay, Margaret Atwood writes, “Let she who has never drawn arms and a moustache on a picture of the Venus de Milo in her Latin book cast the first rubber eraser.” In one of Beaton’s parodies of The Great Gatsby, our hero complains that the green light gives him seizures. Beaton’s work isn’t that subversive. A hip teacher would hand that strip to her students. She would smile when her students told her the strip is better than the corresponding passage in the book. Atwood goes on, “Of course, in order to burlesque a work of literature or an historic event, you have to know it and, in some sense, love it — or at least understand its inner workings.”

In the early ’90s, Adrian Tomine was a prodigy scribbling away at his grim mini-comics and taking notes from Oliveros by mail. His work has grown more somber and mature through the years and now he is a master of narrative in different permutations of the comics form. Françoise Mouly describes the “handsome, stripped-down aesthetics” of his New Yorker covers, which “form a paean to the poignancy of daily life in the big city.” The moments he captures in these covers are pregnant with ambiguity, and he “finds the humanity of a small town within the big one.” His stories depict human beings who struggle with their own mediocrity. Tomine’s work is even-keeled. The lines are careful. The page layouts and panel organization don’t invite any confusion. He has a gentle, classical style and he can bring you just to the edge of tears.

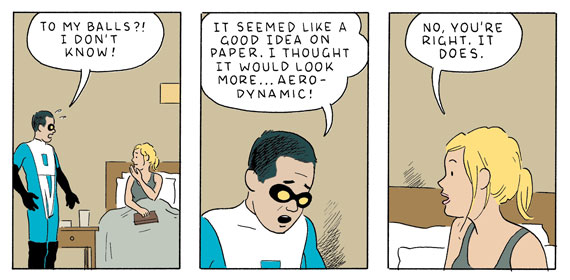

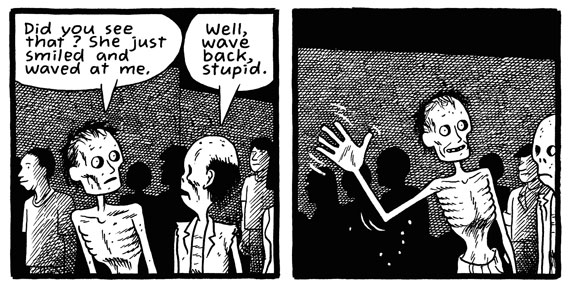

Jonathan Lethem describes Chester Brown as a “citizen of the timeless nation of the dissident soul, as much as Dostoevsky’s underground man. At the same time, he’s also a citizen of a nation of one: Chesterbrownton, or Chesterbrownsylvania, a desolate but charged region he seems to have no choice but to inhabit.” Brown’s subjects veer between the respectable and the borderline subversive. His best-known book Louis Riel is now a staple of Canadian public schools. Paying for It is a memoir of his life as a john. The anthology includes “The Zombie Who Liked the Arts,” a tale from 2007 about a zombie’s infatuation with a human female. These are stories about lonely men, a would-be revolutionary who fights madness, and lovers who dislike their own bodies. Brown’s connection to the underground may be less tenuous, but unlike the folks at RAW and Weirdo, unlike Fyodor Dostoevsky for that matter, he doesn’t hide his polish.

Are these books threatening? In his 2005 book Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature, Charles Hatfield noted that the appeal of the comix underground in the 1970s required the medium of the traditional comic book itself, and the ironies that involved using a medium associated with the “jejune” to discuss illicit, “adult” topics. “[T]he package was inherently at odds with the sort of material the artists wanted to handle, and this gave the comix books their unique edge.” I don’t know if the packaging still matters in the same way, if the placement of Tomine’s mature, sad stories within the firm pages of a graphic novel causes such a disjuncture.

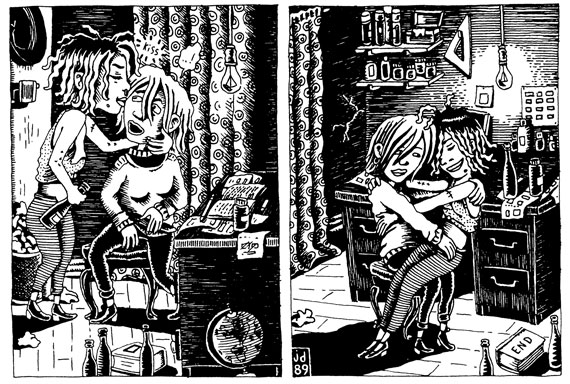

My special edition of Julie Doucet’s exploration of sexual insanity Lève Ta Jambe Mon, Poisson Est Mort! comes complete with a lithograph of a nude belly dancer on the frontispiece and a rave review from ArtForum on the jacket cover. Sean Rogers describes Doucet’s “beguiling forays into an untrammeled imagination, rich with fantastic displays of menstrual flow, severed unmentionable body parts, and inanimate objects forced into service for pleasure.” Doucet is one of D&Q’s more anarchic writers and it may be true that this finely crafted hardbound edition cannot contain her sexuality. But I don’t know if it’s any more scandalous to read Leaves of Grass or Portnoy’s Complaint in a Library of America edition.

The packaging of these books matters for other reasons. Eleanor Davis, the author of How to Be Happy, explains why:

The packaging of these books matters for other reasons. Eleanor Davis, the author of How to Be Happy, explains why:

Loving a book containing prose is like loving a cup filled with a wonderful drink: the cup and drink are only connected by circumstance. Loving a comic book is different. The content and the form of a comic are connected inextricably. The little autonomous drawings are held tightly in the pages of the book the comic is printed in, and they cannot get away. When you hold the comic book, you hold those worlds. They are yours.

Drawn and Quarterly publishes extraordinary comics. And because they are an extraordinary company they know to make extraordinary books for these comics to live in.

It’s not irony that makes the fine hardcover editions of Beaton, Tomine, Brown and Doucet so good, it’s the craftsmanship that marries the content comfortably with the medium, a craftsmanship that understands that a small, standard, novel-size hardcover is appropriate for the spare intimate melancholy of Brown’s I Never Liked You, and that a large, flat, Tintin-like edition is appropriate for the grim fantasy of Daniel Clowes’s The Death-Ray. The various forms of packaging in D&Q’s catalogue simply offers an added texture to each of their creators’ distinct voices.

It’s not irony that makes the fine hardcover editions of Beaton, Tomine, Brown and Doucet so good, it’s the craftsmanship that marries the content comfortably with the medium, a craftsmanship that understands that a small, standard, novel-size hardcover is appropriate for the spare intimate melancholy of Brown’s I Never Liked You, and that a large, flat, Tintin-like edition is appropriate for the grim fantasy of Daniel Clowes’s The Death-Ray. The various forms of packaging in D&Q’s catalogue simply offers an added texture to each of their creators’ distinct voices.

After 25 years, the D&Q artists’ formalist methods, their wry sense of humor, their careful delineation of human emotions, their firm grasp of the comic book/graphic novel as a medium have become not just familiar to comics readers but also the standard for quality comics. Their content, for the most part, is not shocking, and even the subversive voices are much less threatening now than they were before. Brown’s discussion of prostitution is no more provocative than Dan Savage’s. Doucet’s frank discussion of female sexuality was more shocking in the early ’90s than it will ever be again. These artists were never revolutionaries. They were never reactionaries either. They are Burkean liberals of the comics form.

4.

For all its self-congratulation, the anthology does have a sense of humor about itself, the comics industry, and comics celebrity. The book contains a new story from Jillian Tamaki about a D&Q intern who finds fame and fortune after Oliveros fires her for writing a blog post critical of the company. It includes a handwritten note from Spiegelman to Oliveros declining the editor’s request. “I’m a big fan of Julie’s work and I can probably be bullied into giving a quote but would appreciate being left off the hook only because I’ve had to write so many damn blurbs recently. I dunno.” The book begins with a short strip by Chester Brown, “A History of Drawn & Quarterly in Six Panels,” which depicts Oliveros’s advance from youth to middle-age. In the final panel, Oliveros stands alone on a cold, quiet Montreal street.

Oliveros is retiring this year. Peggy Burns, the publicist who moved to D&Q from DC Comics, will now head the company. This anthology stands as a monument to Oliveros and what he accomplished. He discovered extraordinary talent, he widened the audience for non-superhero comics, he created a minor Canadian institution, and he published forgotten comics that would otherwise have been left to the archives. (D&Q has a secondary role as an NYRB Classics of comics, publishing reprints of vintage American comics creators like John Stanley and translations of classic foreign artists and writers like the Finnish author Tove Jansson.) With those accomplishments behind him, the message of Brown’s strip is ambiguous, but I take it to be this: The comics industry doesn’t really change anything. Most of the world is indifferent to your work just as most of the world is indifferent to poetry. This art form of comics will not bring you any closer to enlightenment and it will not bring you any great happiness. It won’t bring you any misery either. Comics makers and comics readers will grow older and come a little bit closer to death, the same way they would if they followed another vocation or indulged in another pastime.

Some of D&Q’s comics may have educated a few minds, but most of the publisher’s craftsmen embrace their own irrelevance. When I was young, I read Maus, Watchmen, and The Dark Knight Returns because they were about mass death, because they were strange, because they treated violence in a way that I thought was real. I still have them on my shelf and thumb through them now and again, but their appeal has changed. Watchmen, I realize now, is a comedy. The Dark Knight Returns is pretty funny too. Maus is as much about the horrors of the present as it is about the horrors of the past. I read Beaton, Brown, Tomine, and the rest because, in every well-placed line, in every well-told joke, they remind me that monotony has its own pleasures and comics don’t have to be important.