1.

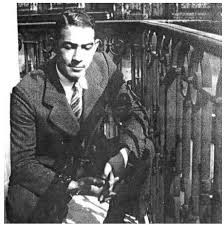

I remember when I began to hate Patrick Modiano. It was in November, 1978. Lingering at the newsstand next to the old Arts Cinema in Cambridge, England, waiting to catch a matinée and leafing through the latest copy of the magazine Le Nouvel Observateur, I came across a photo that soured my entire day.

I’d begun to teach myself French some six months earlier, having had a useless three years of it in high school, and another wasted two semesters in college. I’d learned nothing. Rien. So looking through French news magazines was a bit of an ego boost. The articles and captions were as simple to follow as Monsieur le Président Valéry Giscard d’Estaing’s very slow and deliberate delivery before he faded into obscurity.

There Modiano is, smiling at me, gloating over his newly-crowned Prix Goncourt novel Rue des Boutiques Obscures (Missing Person), seeming to say, “Mon ami, you are a loser,” while a bank of excited press photographers crouches to capture his image. He had good hair, he was young, I had good hair, I was young, but my career as a published author was still a few very long years away. I had travelled 3,000 miles to make a career for myself, and here I was, looking at the face of success. And so, privately, without any basis in reality, without having read a single word by him, I turned my wrath upon Patrick Modiano. What is it Gore Vidal used to say? Whenever a friend succeeds, a little something in me dies. I’d reached the stage in which total strangers were flaying me alive.

The damage wasn’t permanent. Having lingered far too long over Voltaire and Guy de Maupassant and Alphonse Daudet’s incredibly tedious Tartarin de Tarascon, I needed something contemporary to challenge me. At the time I’d been doing a good deal of research into the German Occupation of Paris for a novel that in fact became my first to see the light of publication, and Modiano’s work, being set during that period, was suddenly back on my radar screen. I picked up a copy of his first novel, La Place de l’Étoile, set during the Occupation of Paris and published when this wunderkind was barely into his 20s. It has just been issued in English in what the publisher calls The Occupation Trilogy: three titles, three different translators, each set during the time of the German Occupation: the ground zero of Modiano’s body of work, the foundation for everything that will come after, though after these three titles the Occupation will stand always at an angle to his novels, a shadow cast over the succeeding volumes of what is, even by his own estimation, really a single, long work. When he faces the Occupation head-on once again, it’s with Dora Bruder, his masterful nonfiction (and to some extent autobiographical) story of a missing Jewish girl and the author’s attempts to understand her fate and give her a second life.

The damage wasn’t permanent. Having lingered far too long over Voltaire and Guy de Maupassant and Alphonse Daudet’s incredibly tedious Tartarin de Tarascon, I needed something contemporary to challenge me. At the time I’d been doing a good deal of research into the German Occupation of Paris for a novel that in fact became my first to see the light of publication, and Modiano’s work, being set during that period, was suddenly back on my radar screen. I picked up a copy of his first novel, La Place de l’Étoile, set during the Occupation of Paris and published when this wunderkind was barely into his 20s. It has just been issued in English in what the publisher calls The Occupation Trilogy: three titles, three different translators, each set during the time of the German Occupation: the ground zero of Modiano’s body of work, the foundation for everything that will come after, though after these three titles the Occupation will stand always at an angle to his novels, a shadow cast over the succeeding volumes of what is, even by his own estimation, really a single, long work. When he faces the Occupation head-on once again, it’s with Dora Bruder, his masterful nonfiction (and to some extent autobiographical) story of a missing Jewish girl and the author’s attempts to understand her fate and give her a second life.

2.

Unlike Marcel Proust’s great novel, and unlike the romans fleuves of the last century, such as Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time, Modiano’s work, including his most recent novel, Pour Que Tu Ne Te Perdes Pas Dans Le Quartier (So You Don’t Get Lost in the Neighborhood), released in France just before he was awarded the Nobel Prize, is more a series of incremental epiphanies on the past, on lost opportunities, on lost people, on the small gaps in memory that leave his narrators and protagonists in a world from which they are one step removed. The language in the later books is uncomplicated, and what the author leaves out is as important as what he puts on the page.

Unlike Marcel Proust’s great novel, and unlike the romans fleuves of the last century, such as Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time, Modiano’s work, including his most recent novel, Pour Que Tu Ne Te Perdes Pas Dans Le Quartier (So You Don’t Get Lost in the Neighborhood), released in France just before he was awarded the Nobel Prize, is more a series of incremental epiphanies on the past, on lost opportunities, on lost people, on the small gaps in memory that leave his narrators and protagonists in a world from which they are one step removed. The language in the later books is uncomplicated, and what the author leaves out is as important as what he puts on the page.

What readers find most audacious about La Place de l’Étoile is how intimate the writing is. To deal with a period in which one never lived, to make a leap of imagination and bring the voice of the past vividly and credibly to life, is very much a part of what being a novelist is. But the difference between the historical novelist — who, in adding facts and details and color in hoping to contextualize the fiction, inevitably distances the readers — and what Modiano does in this trilogy is to lend an immediacy and an intimacy to the muddy tide of those years, catching the language, the flow, the Zeitgeist of the period without once having to step back to situate us in the narrative. Since La Place de l’Étoile I haven’t stopped following Modiano, reading each new volume as it’s released, and celebrating his being awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. My apologies, monsieur. My rancor was entirely misplaced.

3.

The title, La Place de l’Étoile, the epigraph informs us, comes from a Jewish story:

In June 1942, a German officer approaches a young man and says, “Excuse me, monsieur, where is the Place de l’Étoile?” The young man gestures to the left side of his chest.

The Place de l’Étoile is both a famous square in central Paris and the place on the body where Jews under the German Occupation were required to wear the Yellow Star, the word juif sewn inside it, over their heart. Modiano had begun writing this in the summer of 1966, when he was 21, and the manuscript was handed to the redoubtable French publisher Gallimard by the great Raymond Queneau, who had been a friend of both the young author and his mother, the Belgian-born actress Louisa Colpeyn. (All autobiographical details are drawn from Denis Cosnard’s indispensable Dans la Peau de Patrick Modiano, published by Fayard in 2010 and not yet available in English translation.)

It was eventually published in 1968, when Modiano was 23 (though everyone believed he was only 21; for several years, out of homage to his late brother Rudy, he had claimed his year of birth as 1947) and it made of him an instant literary phenomenon. As with his second novel, Night Watch, the main character exists in the slippery surreal space of Occupied Paris, where identities shift with one’s loyalties, often vanishing behind several aliases. Modiano makes vividly clear what the German Occupation meant to the French: it was never an unambiguous us-versus-them situation; some openly collaborated with the Nazis, others courageously resisted. And then there was that cloudy intermediate no man’s land occupied by those who played both sides: serving their French masters one day, placating their German ones the next, and that’s where Modiano’s novel is situated. It’s an audacious, ambitious, risky work, especially for a young, first-time novelist, for he was writing in the voice of a Jew who is working with the French Gestapo. This is an author who launched a career by decidedly not playing safe.

Modiano did not come unprepared when he set out to write that first novel. It was in his genes from the start. As he relates in his sort-of-life (to borrow Graham Greene’s title), Pedigree, translated by Mark Polizzotti and just out from Yale University Press, his father, of Italian-Jewish parentage, had been enmeshed in the two worlds that Paris became after 1940, and because, like a virus, the Occupation and its hazy aftereffects had remained long after the last German had left the city, the young Patrick had been drawn into a life filled with colorfully disreputable characters who lingered on into postwar France: real people who drift in and out of his novels (from Night Watch: “I have invented nothing. All the people I have mentioned really existed”): phantoms from a lost world, the displaced many who had done their worst during the war only to find themselves surviving in a self-imposed purgatory, swinging between doomed love affairs, petty crime, the company of faded movie stars, smarmy bands of South-of-France gigolos, and the melancholic regret of Russian émigrés; the comforting oases of rose-tinted, cognac-softened memory. Like them, Modiano’s father had played both sides: dealing with the gangsters of the French Gestapo, endlessly cutting deals on the black market, and refusing to wear the yellow star required by German law. Albert Modiano was neither here nor there, neither one thing or another, a creature of the night forever on the make, a man of such intense self-regard that he could simply cast away his children like so many business deals gone sour.

Modiano did not come unprepared when he set out to write that first novel. It was in his genes from the start. As he relates in his sort-of-life (to borrow Graham Greene’s title), Pedigree, translated by Mark Polizzotti and just out from Yale University Press, his father, of Italian-Jewish parentage, had been enmeshed in the two worlds that Paris became after 1940, and because, like a virus, the Occupation and its hazy aftereffects had remained long after the last German had left the city, the young Patrick had been drawn into a life filled with colorfully disreputable characters who lingered on into postwar France: real people who drift in and out of his novels (from Night Watch: “I have invented nothing. All the people I have mentioned really existed”): phantoms from a lost world, the displaced many who had done their worst during the war only to find themselves surviving in a self-imposed purgatory, swinging between doomed love affairs, petty crime, the company of faded movie stars, smarmy bands of South-of-France gigolos, and the melancholic regret of Russian émigrés; the comforting oases of rose-tinted, cognac-softened memory. Like them, Modiano’s father had played both sides: dealing with the gangsters of the French Gestapo, endlessly cutting deals on the black market, and refusing to wear the yellow star required by German law. Albert Modiano was neither here nor there, neither one thing or another, a creature of the night forever on the make, a man of such intense self-regard that he could simply cast away his children like so many business deals gone sour.

As he describes it in Pedigree, Modiano was essentially abandoned by both his parents, “like a mutt with no pedigree,” as he puts it: his mother was consumed with her life as an actress and treated her eldest child like an accessory, a thing that could be left wherever to be looked after by others, and his father showed him more or less open disdain. It was what bonded him to his brother Rudy, who died at 10 of leukemia, and of whose death he heard as a kind of casual aside: “On the road to Paris, my Uncle Ralph, who was driving, pulled over and stepped out of the car, leaving me alone with my father. In the car, my father told me my brother had died. I had spent the afternoon with him the previous Sunday in our room on Quai de Conti. We had worked on our stamp collection.” As he also writes in Pedigree, “Apart from my brother, Rudy, his death, I don’t believe that anything I’ll relate here truly matters to me.”

4.

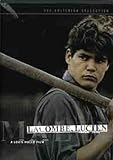

La Place de l’Étoile (translated by Frank Wynne) is as much a novel about language as it is about the narrator, a kind of EveryJew named Raphaël Schlemielovitch, “the Indispensable Jew,” “the official Jew of the Third Reich,” as he calls himself, who is identified with all the famous Jewish authors who preceded him, most notably the half-Jewish Marcel Proust. It’s a Céline-esque spew of a narrative, full of pastiche and alive with the bile and dark wit of a man who has sold his soul to the worst of his generation. It’s a journey to the end of a nightmare set in a time when trust becomes an item to be retailed, along with names and reputations, to the highest bidder, almost always someone with solid friends in the Occupationist hierarchy. It’s a world in which once-loyal French men and women are sucked into the gravitational pull of the collaborationist universe, like the young Lucien in Louis Malle’s film Lacombe, Lucien, with a script by Modiano, where the temptations of power and the ratatat of automatic weaponry are eerily close to what is happening today with young Westerners being drawn to the barbarism of ISIS.

La Place de l’Étoile (translated by Frank Wynne) is as much a novel about language as it is about the narrator, a kind of EveryJew named Raphaël Schlemielovitch, “the Indispensable Jew,” “the official Jew of the Third Reich,” as he calls himself, who is identified with all the famous Jewish authors who preceded him, most notably the half-Jewish Marcel Proust. It’s a Céline-esque spew of a narrative, full of pastiche and alive with the bile and dark wit of a man who has sold his soul to the worst of his generation. It’s a journey to the end of a nightmare set in a time when trust becomes an item to be retailed, along with names and reputations, to the highest bidder, almost always someone with solid friends in the Occupationist hierarchy. It’s a world in which once-loyal French men and women are sucked into the gravitational pull of the collaborationist universe, like the young Lucien in Louis Malle’s film Lacombe, Lucien, with a script by Modiano, where the temptations of power and the ratatat of automatic weaponry are eerily close to what is happening today with young Westerners being drawn to the barbarism of ISIS.

This dreamlike narrative allows notorious anti-Semitic writers such as Louis-Ferdinand Céline to be identified as Jews, where Sigmund Freud gets to quote Jean-Paul Sartre, and Franz Kafka is the elder brother of Charlie Chaplin. At one point the narrator relates a little side story that is also firmly based in family lore:

His own father had also encountered Gérard the Gestapo. He had mentioned him during their time in Bordeaux. On 16 July 1942 Gérard had bundled Schlemilovitch père into a black truck: ‘What do you say to an identity check at the rue Lauriston and a little spell in Drancy?’ Schlemilovitch fils no longer remembered by what miracle Schlemilovitch père escaped the clutches of this good man.

In Pedigree the author writes of his father telling him about his arrests during the Occupation, and his sheer good fortune in escaping deportation to Auschwitz:

And he told me of a second arrest, in the winter of 1943, after “someone” had denounced him. He had been brought to the Depot, from where “someone” had freed him…He said only that the Black Marias had made the rounds of the police stations before reaching the lockup. At one of the stops, a young girl had got on and sat across from him. Much later, I tried, in vain, to pick up her trace, not knowing whether it was in the evening of 1942 or in 1943.

The “young girl” in question was Dora Bruder, the subject of one his most celebrated works. Albert Modiano managed to escape; her future was, of course, much more horrible.

La Place de l’Étoile is a journey into the mind of a man firmly screwed into the darkest period of 20th-century French history as told by the Marx Brothers. But it’s also a way for the author to attempt to come to grips with what his father did during those very dark times. Without some knowledge of the leading lights of collaborationist Paris some references will seem obscure, and the footnotes are either unhelpfully sketchy or simply wrong: the banker and embezzler Alexandre Stavisky, appears here as “Stavinsky.”

These three novels gathered into a single volume constitute the primal stew of all of Modiano’s books. Shifting loyalties, hidden identities, and missing people regularly appear in a body of work that is so remarkably consistent that, taken as a whole, they seem to be one long novel.

The narrator in Ring Roads, the third of this so-called trilogy — published in Caroline Hillier’s translation, but newly “revised” by Wynne — a hack writer named Serge Alexandre, is caught up in what he calls a “hopeless enterprise” in trying to track down his father. In doing so he has to descend into the dregs of society: “Pornographer, gigolo, confidant to an alcoholic and to a blackmailer…Would I have to sink even lower to drag you out of your cesspit?”

This novel sets the central theme of all of Modiano’s work: the search. In Ring Roads it’s for his father; for the amnesiac protagonist of the Goncourt-prize winning Rue des Boutiques Obscure (available in translation as Missing Person) it’s for himself; and this search, so different from that of Proust’s great novel, establishes the groundwork for all of the work that follows, though stylistically we won’t see another like La Place de l’Étoile again. After this, and the second title in the volume, Night Watch, to a degree an early version of his screenplay Lacombe, Lucien, his work grows increasingly more spare, achieving what the French call Modiano’s petite musique, this allusive, elusive approach to writing that has not only marked his novels, but also his speech. Watching filmed interviews with him (most notably with Bernard Pivot, host of Apostrophes), one hears him respond with maybe a few words, frequent ellipses, and sentences that simply trail off without conclusion. The unsayable is as powerful as the words surrounding it.

Though after Ring Roads the Occupation remains in the background, what follows are works of short fiction that examine not just the themes of loyalty and deception, but also the temperament of a series of young narrators who could be thought of as Modiano himself. Taken as a whole, and as a work-in-progress, his body of work is about perception, deception, disappointment, and discovery, borrowing from the conventions of the detective genre.

For those coming anew to Modiano, reading Pedigree first might be a wise choice. His life, such as he tells it here, is as extraordinary and as bizarre as the situations of his fiction. The fact that Pedigree was published 37 years after the publication of La Place de l’Étoile says much about Modiano’s famous reticence about his family and background, on which, until then, he had been notably elliptical. His childhood had been a remarkable one, and by today’s standards it would have been considered borderline abusive. The lack of parental involvement and even interest in Patrick’s well-being is astonishing, and his bitterness is understandable. But it also goes a long way to show what made him a writer.

As the writer Jenny Diski wrote in a recent essay for the London Review of Books, a memoir is “a form that in my mind plays hide and seek with the truth.” Such is the universe of Patrick Modiano.