1.

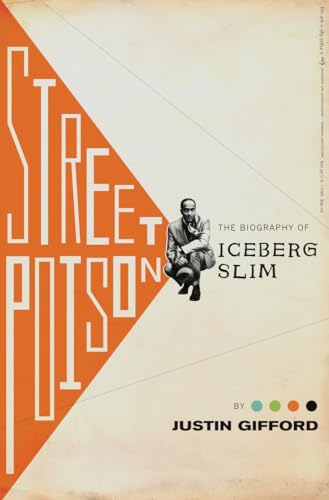

Justin Gifford’s timing is impeccable. He has just published his second book, Street Poison: The Biography of Iceberg Slim, a vivid retelling of the fluorescently eventful life of a hardened pimp, drug addict, and convict who turned to writing highly autobiographical pulp fiction about black street life. Though published by a small press and available mostly in drugstores, liquor stores, barbershops, and prisons, Iceberg Slim’s books, including his scorching autobiography Pimp: The Story of My Life, sold millions of copies and influenced countless writers, actors, directors, comedians, and musicians, including the creators of blaxploitation films, street fiction, and gangsta rap. Chris Rock, Ice-T, and Andrew Vachss are major fans. “He is arguably one of the most influential figures of the past fifty years,” Gifford writes, “and yet, apart from what he reveals in his own writings, very little is known about this fascinating and contradictory character.”

Gifford’s worthy goal is to right this wrong. He tells us that Iceberg Slim was born Robert Lee Moppins Jr., in Chicago in 1918, and later changed his name to Robert Beck. His abusive father left soon after his birth, and his mother abandoned her devoted second husband in favor of a street hustler, a pivotal event in young Robert’s life. Another was his sexual abuse at the age of three by a babysitter. These traumas spawned a deep ambivalence toward women, especially his mother. He despised school — he got expelled after a brief stint at Tuskegee Institute because he spent most of his time in juke joints — and he saw no future in straight, menial jobs. He would do time in prisons that were little more than academies for refining criminal skills. Later he described his world as a “black hell” awash in “the poisonous pus of double standard justice, racial bigotry and criminal economic freeze-out.” It was almost inevitable that he got seduced by the dazzle of the pimp life.

Gifford’s worthy goal is to right this wrong. He tells us that Iceberg Slim was born Robert Lee Moppins Jr., in Chicago in 1918, and later changed his name to Robert Beck. His abusive father left soon after his birth, and his mother abandoned her devoted second husband in favor of a street hustler, a pivotal event in young Robert’s life. Another was his sexual abuse at the age of three by a babysitter. These traumas spawned a deep ambivalence toward women, especially his mother. He despised school — he got expelled after a brief stint at Tuskegee Institute because he spent most of his time in juke joints — and he saw no future in straight, menial jobs. He would do time in prisons that were little more than academies for refining criminal skills. Later he described his world as a “black hell” awash in “the poisonous pus of double standard justice, racial bigotry and criminal economic freeze-out.” It was almost inevitable that he got seduced by the dazzle of the pimp life.

Street Poison paints a rich picture of a young pimp’s unsentimental education. The trade secrets were passed down by word of mouth from veteran pimps in the form of the unwritten pimp “book.” Young Beck drank in these lessons, spent hours practicing his come-ons. As he put it with typical flair, “I had memorized an arsenal of howitzer motivators I’d kept on instant alert in my skull. I’d barraged them daily for three years to persuade a ten ho stable to hump my pockets obese.” Beck was in awe of the smooth Chicago pimps, who drove Duesenbergs and kept pet ocelots. One of his most influential mentors was a notorious Chicago pimp and killer named Albert “Baby” Bell, who set an impossibly high standard of cruelty. “Bell’s form of pimping was more violent and manipulative than anything Beck had ever seen in prison or in the taverns of Milwaukee,” Gifford writes. “His main philosophy was ‘One whore ain’t got but one pussy and one jib. You got to get what there is in her as fast as you can…’” Bell encouraged Beck to beat his whores with a coat hanger when they got out of line because “ain’t no bitch, freak or not, can stand up to that hanger.”

Beck had never been shy about using physical force, but Bell showed him that he had a serious career liability: He didn’t hate women enough. Beck admitted as much in later interviews: “I had a very good mother. Most of the successful pimps in those days had been dumped in garbage cans, had been abandoned and had never known maternal love. They were the cold-blooded ones…But I always had that sucker streak in me…I was never the best pimp. To be a great pimp, you’ve really got to hate your mother.”

That shortcoming didn’t stop him from having a long career with all the conventional trappings: the hotel suites, the fine clothes, the jewelry, the Cadillacs, the dope (Beck was partial to speedballs), and the inevitable prison stretches. His street name was oddly high-tone: Cavanaugh Slim.

After his release from the grim Chicago House of Correction in 1962, Beck left the pimp life and relocated to Los Angeles, where he hoped to reconcile with his dying mother. He started a family and worked straight jobs. He also started writing, acting out the stories of his life for his white common-law wife, Betty Mae Shew, who typed them up. Together, they turned Cavanaugh Slim into Iceberg Slim and in 1967 they sold Pimp to Holloway House, a small L.A. publisher. The book became an underground sensation, and several autobiographical novels followed. Within a few years, Iceberg Slim was the bestselling black author in America.

Small wonder. His writing leaps off the page. Here, for instance, are an ex-con’s rueful ruminations after he gets double-crossed by his former cellmate and decides to salve the wound by finding himself a whore:

It was black ghetto Christmas. Saturday night! Easy to cop a ho! I’d guerilla my Watusi ass into a chrome-and-leather ho den and gattle-gun my pimp-dream shit into some mud-kicker’s frosty car. I pimp-pranced toward a ho jungle of neon blossoms a half mile away. Some ass-kicker was a cinch to be a ho short when the joints folded in the a.m.

In Pimp, Beck recounts being transfixed the first time he heard a group of pimps performing a “toast,” a cousin of the dozens, a bawdy, nearly Shakespearean roundelay of boasts, puns, putdowns, and one-ups-man-ship. Neither subtle nor politically correct, the pimp toast proved electrifying to certain ears. As Gifford writes, “Although he couldn’t know it at the time, Beck was witnessing one of the origins of gangsta rap and hip-hop in these toasts…Like the dozens and the pimp book, these toasts grew out of African American oral expressions, and they became the direct forerunners of the comedy of Rudy Ray Moore and the gansta rap of N.W.A., Ice-T and Snoop Dogg.” Rudy Ray Moore’s bad-ass character Dolemite, for instance, concocted this toast-inspired putdown: “You ain’t nothin’ but a born-insecure, rat-soup-eatin’, barnyard muth-a-fucka!”

Which brings us back to Justin Gifford’s impeccable timing.

2.

A few days after Street Poison was published, a splashy Hollywood production called Straight Outta Compton, directed by F. Gary Gray, opened in theaters nationwide. It tells the 1980s origin story of N.W.A., a group of young rappers in the Compton section of Los Angeles led by three buddies, Eazy-E (played by Jason Mitchell), Dr. Dre (Corey Hawkins) and Ice Cube (O’Shea Jackson Jr., Ice Cube’s real-life son). As Gifford points out, numerous hip-hop artists have drawn on the legend of Iceberg Slim for their monikers and their attitude. He singles out Ice Cube and Ice-T, but he could have added the Houston rappers Pimp C and Slim Thug, among many others.

Like Robert Beck, the members of N.W.A. were faced with limited options in terms of jobs and housing. As crack cocaine and gang warfare engulfed their corner of L.A., they repeatedly tasted the wrath of a brutal police force. Joining the drug trade was one career choice — the movie opens with Eazy-E making a delivery to a drug house moments before the police storm the place — but these buddies decide to pursue music instead. You know the rest.

Though it’s a sanitized version of N.W.A.’s story, Straight Outta Compton does have its moments, including a live performance of the incendiary anthem “Fuck tha Police,” which triggers a riot inside a Detroit arena. Several songs on the soundtrack reveal gangsta rap’s twin lodestars: the prizing of flash and money, and the simultaneous devaluing of women as nothing more than sex toys and furniture. In one telling scene, Dr. Dre and Eazy-E are poolside at their respective compounds, talking by phone about a possible N.W.A. reunion — while Dre’s woman reads a magazine and Eazy-E’s touches up her toenail polish. As N.W.A. sings in “Gangsta Gangsta,” “Life ain’t nothin’ but bitches and money.”

Straight Outta Compton stops far short of revealing the dark flipside of this mantra — gangsta rappers’ history of physical violence against women, something Iceberg Slim knew a great deal about. As the movie debuted, three women came forward with stories about receiving vicious physical beatings from Dr. Dre, who had recently sold his Beats company to Apple for $3 billion. After scoffing at these charges for decades, Dr. Dre suddenly came clean, issuing an apology that made the front page of The New York Times: “Twenty-five years ago I was a young man drinking too much and in over my head with no real structure in my life. However, none of this is an excuse for what I did…I apologize to the women I’ve hurt.” The timing of this apology made it impossible not to question its sincerity. It sounded like a billionaire’s advisers had finally convinced him that misogyny is bad for business.

Dubious as this sudden turnabout was, it couldn’t match the somersaults of the movie’s director, F. Gary Gray. The original script included Dr. Dre’s beating of the hip-hop journalist Dee Barnes, which resulted in his plea of no contest to assault and battery charges. (Dr. Dre was sentenced to community service and probation, fined $2,500, and ordered to make a public service announcement denouncing domestic violence. A civil suit was settled out of court for an undisclosed sum.) Asked why the scene was dropped from the final version of “Straight Outta Compton,” Gray said the filmmakers decided the movie “wasn’t about a lot of side stories.” He added, “You can make five different N.W.A. movies. We made the one we wanted to make.”

What they did not want to make, obviously, was a movie that would make hip-hop’s first billionaire look bad.

3.

Once again, Iceberg Slim was way ahead of the curve. Even before his literary career began to take off, he’d become a supporter of the Black Panthers and of another former pimp who turned his life around, Malcolm Little, aka Detroit Red, aka Malcolm X. As Beck’s autobiography and fiction gained popularity among black readers, he expanded into writing essays, vignettes, and personal deliberations, also lecturing at libraries and colleges and appearing on television. He was a tireless promoter of black liberation and a tireless critic of the racism that had shaped his life — the shabby housing and limited job opportunities, the police and the prisons, the undying disdain of white America. The street was his pulpit and street people were his flock, leading him to disparage not only white racists but also the black bourgeoisie, all the prosperous movie stars, professors, preachers, politicians, and landlords who are nothing more than “outlaw whores in the stable of the white power structure.”

Gifford, an associate professor of English at the University of Nevada, Reno, is also the author of Pimping Fictions: African American Crime Literature and the Untold Story of Black Pulp Publishing. He spent 10 years researching and writing Street Poison, and though his prose is sometimes wooden, his knowledge and affection for his subject are evident on every page. Near the book’s end, Gifford recounts Beck’s appearance on a TV show called Black Journal, where he gave an interview that might have been addressed personally to Dr. Dre and his fellow gangsta rappers. Gifford writes:

Gifford, an associate professor of English at the University of Nevada, Reno, is also the author of Pimping Fictions: African American Crime Literature and the Untold Story of Black Pulp Publishing. He spent 10 years researching and writing Street Poison, and though his prose is sometimes wooden, his knowledge and affection for his subject are evident on every page. Near the book’s end, Gifford recounts Beck’s appearance on a TV show called Black Journal, where he gave an interview that might have been addressed personally to Dr. Dre and his fellow gangsta rappers. Gifford writes:

Here he outlined how his failed life as a pimp ultimately led to his revolutionary consciousness. As he proclaims at the end of the interview, ‘I’m here tonight appearing before you as a well individual. Free of the street poison that put me into the kind of position where I brutalized and exploited our black queens. You have to have a realization that when you exploit your own kind, that you are, in effect, counter-revolutionary.’

Beck had been both exploiter and exploited. He received a fraction of the royalties due him from Holloway House — which meant, ironically, that he got pimped by his publisher. Beck had also been an eyewitness to the Watts riots of 1965, and as he lay dying of diabetes and gangrene in a Los Angeles hospital bed in 1992, fire was again sweeping the city — following the acquittal of four white L.A. cops for the brutal, videotaped beating of black motorist Rodney King. So much had changed, so little had changed. So little has changed. But we can be glad that one thing remains the same: Iceberg Slim has something timeless to say not just to gangsta rappers, but to all Americans, black and white, rich and poor, male and female, criminal and law-abiding. It’s in his books, and it’s in the pages of the timely and richly rewarding biography Street Poison.