Two debut novels – one freshly published, the other on its way to becoming a classic – have reminded me that for the past century American writers and artists have been obsessed with that shimmering, sexy, liberating, lethal contraption known as the automobile. Small wonder. Is there a more potent metaphor for American restlessness, for the American hunger for status and sex, for the American tendency to wind up, broken and bloody, in a ditch?

In a thesis written in 2007, a doctoral candidate named Shelby Smoak neatly summed up the role of the automobile in American fiction as a way for characters to experience “violence, sacredness and consumption.” Reversing this order, cars give writers and artists a way to talk about that unholy troika: status, escape (including sexual escapades), and death. In the bargain, the automobile, which introduced the concept of planned obsolescence back in the 1930s, is the shiny embodiment of American capitalism’s relentless quest to make consumers hunger for the next new thing, whether they need it or not.

The first of the two debut novels that brought all this home to me is Lot Boy by Buffalo native Greg Shemkovitz, just published by Sunnyoutside Press. It’s the story of Eddie Lanning, a twentysomething fuckup in Buffalo who works as the titular lot boy, performer of the lowliest tasks at the Ford dealership founded by his late grandfather and now run by his father, who’s dying of cancer. All Eddie wants to do is hook back up with his former girlfriend and get the hell out of Buffalo. To finance his escape, Eddie’s working a scam selling hot auto parts from the dealership, which inspires this rosy portrait of the local scenery:

The first of the two debut novels that brought all this home to me is Lot Boy by Buffalo native Greg Shemkovitz, just published by Sunnyoutside Press. It’s the story of Eddie Lanning, a twentysomething fuckup in Buffalo who works as the titular lot boy, performer of the lowliest tasks at the Ford dealership founded by his late grandfather and now run by his father, who’s dying of cancer. All Eddie wants to do is hook back up with his former girlfriend and get the hell out of Buffalo. To finance his escape, Eddie’s working a scam selling hot auto parts from the dealership, which inspires this rosy portrait of the local scenery:

To get here, you have to go through a shitty part of South Buffalo to get to an even shittier section, until you cross a bridge into the wetlands and fields and eventually hit the rundown industrial lakeshore. Seeing all this decay and frozen debris pass by my windows, I realize that the only reason anyone would come here is to sell stolen auto parts to somebody who would only come here to buy them.

Among its many virtues, this novel offers a peek behind the curtain of a world few people have experienced – the claustrophobic, corrupt, filthy, noisy, inefficient and mind-numbingly banal world of a Big Three car dealership. Reading Lot Boy, you’ll find yourself rooting for Eddie’s escape, while coming to understand why the American automobile industry went so far down the toilet that the U.S. taxpayer had to reach in and pull it out. Here’s the terse but uplifting author note at the end of this winning novel: “Greg Shemkovitz left Buffalo.”

Theodore Weesner, who died on June 25 at age 79, published his debut novel in 1972 to foam-at-the-mouth critical praise but modest sales. The Car Thief is the sometimes brutal, sometimes tender story of a troubled teenage boy named Alex Housman whose biography has much in common with Weesner’s. Alex’s hard-drinking mother abandoned him in infancy, and after spending some time in foster care he’s now growing up in a Michigan factory town, living with his alcoholic father, an autoworker. To give his “uncounted” life some account, Alex steals cars and takes them on aimless drives before abandoning them and stealing again. It’s the only means of self-expression available to a boy in such stunted circumstances. Here’s the novel’s opening:

Theodore Weesner, who died on June 25 at age 79, published his debut novel in 1972 to foam-at-the-mouth critical praise but modest sales. The Car Thief is the sometimes brutal, sometimes tender story of a troubled teenage boy named Alex Housman whose biography has much in common with Weesner’s. Alex’s hard-drinking mother abandoned him in infancy, and after spending some time in foster care he’s now growing up in a Michigan factory town, living with his alcoholic father, an autoworker. To give his “uncounted” life some account, Alex steals cars and takes them on aimless drives before abandoning them and stealing again. It’s the only means of self-expression available to a boy in such stunted circumstances. Here’s the novel’s opening:

Again today Alex Housman drove the Buick Riviera. The Buick, coppertone, white sidewalls, was the model of the year, a ’59, although the 1960 models were already out. Its upholstery was black, its windshield was tinted a thin color of motor oil. The car’s heater was issuing a stale and odorous warmth, but Alex remained chilled. He had walked several blocks through snow and slush, wearing neither hat nor gloves nor boots, to where he had left the car the night before. The steering wheel was icy in his hands, and he felt icy within, throughout his veins and bones. Alex was sixteen; the Buick was his fourteenth car.

There is not a shred of sentimentality or self-pity in this book, and it never sinks to the dreary level of a treatise on “the juvenile delinquent problem.” This is a work of art, fuelled by all those purloined Buick Rivieras and Chevy Bel Airs. In the end, like Lot Boy, it is less a coming-of-age story than a story about our shared yearning to escape.

Here are a dozen other writers and artists who have used the automobile to tell stories about Americans on their way to escape, status and death, sometimes all three. This list doesn’t pretend to be exhaustive. Feel free to offer your own additions:

Scott Fitzgerald’s Rolls-Royce

Few cars in American fiction have done as much lifting as Jay Gatsby’s 1922 Rolls-Royce. It’s the status symbol that fairly shouts Gatsby’s nouveau riche bona fides; it’s the dream machine that whisks Gatsby and Nick Carraway through the Valley of Ashes, past the unblinking eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg and onto the Gilded Isle of Manhattan; and finally it’s the weapon that ends Myrtle Wilson’s life and leads her grieving husband to mistakenly seek vengeance against the owner of the deadly Rolls-Royce. Here’s our narrator Nick, who drives a stodgy Dodge, gushing over Gatsby’s versatile automobile:

It was a rich cream color, bright with nickel, swollen here and there in its monstrous length with triumphant hat-boxes and supper-boxes and tool-boxes, and terraced with a labyrinth of wind-shields that mirrored a dozen suns. Sitting down behind many layers of glass in a sort of green leather conservatory, we started to town.

John O’Hara’s Cadillac

Few American novelists were more finely attuned to – or hungrier for – the trappings of status than John O’Hara. The protagonist of his 1934 novel Appointment in Samarra is Julian English, son of an old Gibbsville, Pa., family, snug inside the upper-crust Lantenengo Country Club set, a hard drinker, a philanderer, and a Cadillac salesman at a time when the Depression is bottoming out and Cadillacs are becoming harder to sell. Despite appearances, Julian has problems – a drinking problem, a marital problem, a money problem, plus the fact that a lot of people in town secretly despise him. Julian’s seemingly perfect life unravels in a whiplash blur over the course of three days and, after an unsuccessful seduction attempt in his own living room, he pitches an epic drunk, playing records, smoking, spilling drinks, falling down, getting up, drinking more. Finally he grabs a pack of cigarettes and a fresh bottle of Scotch and goes out the front door and into the garage, where his Cadillac awaits. Then, after closing the garage door and making sure the windows are shut:

Few American novelists were more finely attuned to – or hungrier for – the trappings of status than John O’Hara. The protagonist of his 1934 novel Appointment in Samarra is Julian English, son of an old Gibbsville, Pa., family, snug inside the upper-crust Lantenengo Country Club set, a hard drinker, a philanderer, and a Cadillac salesman at a time when the Depression is bottoming out and Cadillacs are becoming harder to sell. Despite appearances, Julian has problems – a drinking problem, a marital problem, a money problem, plus the fact that a lot of people in town secretly despise him. Julian’s seemingly perfect life unravels in a whiplash blur over the course of three days and, after an unsuccessful seduction attempt in his own living room, he pitches an epic drunk, playing records, smoking, spilling drinks, falling down, getting up, drinking more. Finally he grabs a pack of cigarettes and a fresh bottle of Scotch and goes out the front door and into the garage, where his Cadillac awaits. Then, after closing the garage door and making sure the windows are shut:

He climbed in the front seat and started the car. It started with a merry, powerful hum, ready to go. ‘There, the bastards,’ said Julian, and smashed the clock with the bottom of the bottle, to give them an approximate time. It was 10:41.

There was nothing to do now but wait. He smoked a little, hummed for a minute or two, and had three quick drinks and was on his fourth when he lay back and slumped down in the seat. At 10:50, by the clock in the rear seat, he tried to get up. He had not the strength to help himself, and at ten minutes past eleven no one could have helped him, no one in the world.

It’s a remarkable moment: suicide by status symbol.

Vladimir Nabokov’s Buick

“Nothing,” according to Vladimir Nabokov, “is more exhilarating than philistine vulgarity.” So perhaps it’s not surprising that during their years in America Nabokov and his wife Vera owned a series of cars – Pontiacs, Oldsmobiles, Buicks – manufactured by General Motors, the most vigorous purveyor of philistine vulgarity the world has ever known. One in particular, a 1952 Buick, was crucial to the composition of Nabokov’s masterpiece, Lolita. With Vera at the wheel of the Buick, Nabokov wrote on index cards during transcontinental butterfly-hunting trips in the 1950s, gleefully cataloging the abundant philistine vulgarity whizzing past the windshield. Among the Nabokovs’ preferred lodgings were the Coral Log Motel in Afton, Wyo., and the Bright Angel Lodge on the rim of the Grand Canyon.

“Nothing,” according to Vladimir Nabokov, “is more exhilarating than philistine vulgarity.” So perhaps it’s not surprising that during their years in America Nabokov and his wife Vera owned a series of cars – Pontiacs, Oldsmobiles, Buicks – manufactured by General Motors, the most vigorous purveyor of philistine vulgarity the world has ever known. One in particular, a 1952 Buick, was crucial to the composition of Nabokov’s masterpiece, Lolita. With Vera at the wheel of the Buick, Nabokov wrote on index cards during transcontinental butterfly-hunting trips in the 1950s, gleefully cataloging the abundant philistine vulgarity whizzing past the windshield. Among the Nabokovs’ preferred lodgings were the Coral Log Motel in Afton, Wyo., and the Bright Angel Lodge on the rim of the Grand Canyon.

Lolita, of course, would not have been possible without cars. After Humbert Humbert’s bride (Lolita’s mother) is dispatched by an errant Packard, leaving the top of poor Charlotte Haze’s head “a porridge of bone, brains, bronze hair and blood,” Humbert, now the legal guardian of his prey, takes Lolita on a year-long, 27,000-mile, pedophile’s “joy ride,” during which his illicit lusts are slaked in roadside hostelries called Sunset Motel, U-Beam Cottages, Mac’s Courts, Kumfy Kabins and, most famously, the Enchanted Hunters. This ecstatic wallowing in philistine vulgarity and taboo sex is made possible by “the Haze jalopy with its ineffectual wipers and whimsical brakes.” In Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 movie adaptation of the novel, which Nabokov professed to admire (he wrote the screenplay), the “Haze jalopy” is a pedestrian 1957 Ford station wagon.

There was nothing pedestrian about the chariot the Nabokovs drove.

Jack Kerouac’s Hudson

Which brings us, inevitably, to that Holy Bible of American car novels, Jack Kerouac’s ricocheting pubescent kicks-quest known as On the Road. There are many vehicles in the novel, including cars, trucks and buses, but the most important one is the 1949 Hudson that Dean Moriarty buys on a whim and proceeds to punish until the rear end falls out on the way back from a high old time in a Mexican whorehouse. As impulse purchases go, this one’s a beauty, and Kerouac’s telling of it is instructive. For a writer so dedicated to spontaneous bop prosody and its fluorescent riffs and rambles, Kerouac’s writing could be stunningly flat. Dean’s purchase of the Hornet, so rich with possibilities for rapture, reads like a police blotter:

Which brings us, inevitably, to that Holy Bible of American car novels, Jack Kerouac’s ricocheting pubescent kicks-quest known as On the Road. There are many vehicles in the novel, including cars, trucks and buses, but the most important one is the 1949 Hudson that Dean Moriarty buys on a whim and proceeds to punish until the rear end falls out on the way back from a high old time in a Mexican whorehouse. As impulse purchases go, this one’s a beauty, and Kerouac’s telling of it is instructive. For a writer so dedicated to spontaneous bop prosody and its fluorescent riffs and rambles, Kerouac’s writing could be stunningly flat. Dean’s purchase of the Hornet, so rich with possibilities for rapture, reads like a police blotter:

(Dean) got a job on the railroad and made a lot of money.

He became the father of a cute little girl, Amy Moriarty. Then suddenly he blew his top while walking down the street one day. He saw a ’49 Hudson for sale and rushed to the bank for his entire roll. He bought the car on the spot. Ed Dunkel was with him. Now they were broke. Dean calmed Camille’s fears and told her he’d be back in a month. “I’m going to New York and bring Sal back.” She wasn’t too pleased at this prospect.

“But what is the purpose of all this? Why are you doing this to me?”

“It’s nothing, it’s nothing, darling – ah – hem – Sal has pleaded and begged with me to come and get him, it is absolutely necessary for me to – but we won’t got into all these explanations – and I’ll tell you why… No, listen, I’ll tell you why.” And he told her why and of course it made no sense.”

What made no sense is that Kerouac didn’t do more with glorious iron like this.

Richard Yates’s Pontiac

In the 2008 movie adaptation of Richard Yates’s masterpiece, Revolutionary Road, Frank Wheeler (played by Leonardo DiCaprio) drives a gargantuan, four-door 1954 Buick Roadmaster. The car is miscast. That big bulky Buick is a banker’s car, not the car of a disaffected suburbanite with vague artistic pretensions like Frank Wheeler. But no matter. There are two moments when cars are crucial to the novel’s effect. The first comes when Frank’s wife, April, is driving to rehearsals for a community theater production. It’s important to remember that Revolutionary Road is set in 1955, the year after President Dwight Eisenhower announced his plan to build a system of interstate highways, an acknowledgement that the chrome-encrusted, fire-breathing cars coming out of Detroit were traveling on hopelessly outdated roads. As April and her fellow Players make their way to rehearsal:

In the 2008 movie adaptation of Richard Yates’s masterpiece, Revolutionary Road, Frank Wheeler (played by Leonardo DiCaprio) drives a gargantuan, four-door 1954 Buick Roadmaster. The car is miscast. That big bulky Buick is a banker’s car, not the car of a disaffected suburbanite with vague artistic pretensions like Frank Wheeler. But no matter. There are two moments when cars are crucial to the novel’s effect. The first comes when Frank’s wife, April, is driving to rehearsals for a community theater production. It’s important to remember that Revolutionary Road is set in 1955, the year after President Dwight Eisenhower announced his plan to build a system of interstate highways, an acknowledgement that the chrome-encrusted, fire-breathing cars coming out of Detroit were traveling on hopelessly outdated roads. As April and her fellow Players make their way to rehearsal:

Their automobiles didn’t look quite right either – unnecessarily wide and gleaming in the colors of candy and ice cream, seeming to wince at each spatter of mud, they crawled along apologetically down the broken roads that led from all directions to the deep, level slab of Route Twelve. Once there the cars seemed able to relax in an environment all their own, a long bright valley of colored plastic and plate glass and stainless steel – KING KONE, MOBILGAS, SHOPORAMA, EAT…

The only thing missing is a Kumfy Kabins. This marvelous sketch repays re-reading, especially the way the cars “wince” and “crawl along apologetically” and are finally able to “relax.” But it merely sets the table for one of this bleak novel’s bleakest moments, the night April and a fawning neighbor named Shep Campbell find themselves pawing each other drunkenly in the front seat of Shep’s ’55 Pontiac in the parking lot outside Vito’s Log Cabin alongside Route Twelve:

The noise of their breathing had deafened them to all other sounds: the loud insects that sang near the car, the drone of traffic on Route Twelve and the fainter sounds from the Log Cabin – a woman’s shrieking laugh dissolving into the music of horn and piano and drums.

“Honey, wait. Let me take you somewhere – we’ve got to get out of – ”

“No. Please,” she whispered. “Here. Now. In the back seat.”

And the back seat was where it happened. Cramped and struggling for purchase in the darkness, deep in the mingled scents of gasoline and children’s overshoes and Pontiac upholstery, while a delicate breeze brought wave on wave of Steve Kovick’s final drum solo of the night, Shep Campbell found and claimed the fulfillment of his love at last.

When the deed is done, Shep blurts out that he loves April. She rebuffs this idiotic confession by telling him, “I don’t know who you are.” Then comes the final blow, which will prove to be a death sentence: “And even if I did,” she said, “I’m afraid it wouldn’t help, because you see I don’t know who I am either.”

Ah, the truths that pass back and forth in the sticky back seat of a ’55 Pontiac.

Robert Frank’s Ford

In 1955, the year Revolutionary Road was set, the Swiss-born photographer Robert Frank bought a second-hand 1950 Ford Business Coupe and set out on an epic year-long road trip of his own. Armed with two cameras and many boxes of film, sometimes traveling alone and sometimes accompanied by his wife and their young son, he set out to capture a visual record of what it meant to live in America – the frustrations and joys, the unease, the misgivings people think about but don’t discuss. This was the season of Emmett Till’s murder, the Montgomery bus boycott. The Deep South and Detroit proved to be two particularly fruitful locales for Frank – the hell of Jim Crow and the different hell where people went to escape it.

In 1955, the year Revolutionary Road was set, the Swiss-born photographer Robert Frank bought a second-hand 1950 Ford Business Coupe and set out on an epic year-long road trip of his own. Armed with two cameras and many boxes of film, sometimes traveling alone and sometimes accompanied by his wife and their young son, he set out to capture a visual record of what it meant to live in America – the frustrations and joys, the unease, the misgivings people think about but don’t discuss. This was the season of Emmett Till’s murder, the Montgomery bus boycott. The Deep South and Detroit proved to be two particularly fruitful locales for Frank – the hell of Jim Crow and the different hell where people went to escape it.

“I went to Detroit to photograph the Ford factories,” Frank said, “and then it was clear to me I wanted to do this. It was summer and so loud. So much noise. So much heat. It was hell. So much screaming.”

Frank loved his faceless ’50 Ford because, like him, it was inconspicuous. He saw himself as a detective, or a spy, surreptitiously chronicling the lives he encountered. He usually shot in public places – parks, drive-ins, city sidewalks, political rallies, churches, juke joints. His sympathies, he has said, “were with people who struggled. There was also my mistrust of people who made the rules.”

The resulting book is called The Americans, and today it’s an undisputed classic. The last image in the book shows Frank’s wife Mary and son Pablo asleep in the Ford on the shoulder of a road in Texas. It’s a testament to just how gritty and exhausting the journey was.

Flannery O’Connor’s…Ford?

In what may be her greatest short story, “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” Flannery O’Connor sends a Georgia family off to their doom aboard an automobile of unspecified make. Given the thoroughly middle-class, middle-brow nature of this Atlanta family, I’m going to guess the car was a Ford. It doesn’t really matter. What matters is that the chatterbox grandmother has concealed her cat in a hat box in the back seat, and when it springs onto the shoulder of the driver, the grandmother’s son, Bailey, the car lurches off the road and tumbles into a gulch, landing right-side-up, nobody seriously injured.

Now comes the best part. A car slowly approaches the scene of the accident: “It was a big black battered hearse-like automobile. There were three men in it.”

This unholy trinity are undertakers, all right, three prison escapees – The Misfit, Hiram and Bobby Lee – who set about slaughtering the whole family: husband and wife, son and daughter, infant and finally, most spectacularly, the grandmother. It’s the perfect ending to a perfect story, one that began with the promise of automobile-assisted escape, then progressed to an automotive mishap that led, finally, inevitably, to mass murder. As the story ends, The Misfit and his two psychopath sidekicks plan to fix the mildly damaged Ford and leave the hearse behind. That’s called trading up. That’s what you’re supposed to do with cars in America.

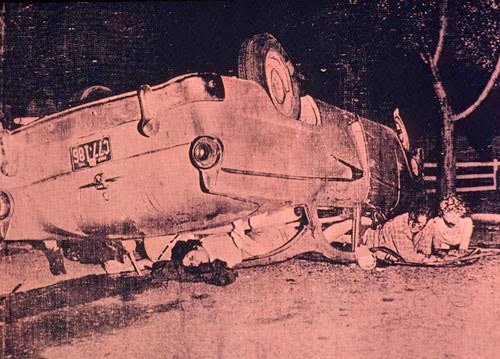

Andy Warhol’s Fords

If Henry Ford’s assembly line introduced the central impulse of the 20th century – the urge to replicate an act endlessly – then Andy Warhol introduced the notion that the replicable event was not only the essence of our age, it was also lowly stuff that could be transformed into high art. And so Warhol mass-produced images of things meant to be consumed in mass quantities, including Coca-Cola bottles, Campbell’s soup cans and Brillo boxes; movie stars (Marilyn, Liz, Elvis); political icons (Mao, Che, Nixon); pop stars (Michael Jackson, John Lennon, Debby Harry); and, inevitably, the automobile and its ubiquitous by-product, the car crash.

In 2013, 50 years after it was painted, Warhol’s “Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster)” sold at auction for $105 million, then the highest price ever paid for the artist’s work. The painting is repeating images of a body inside a mangled car after a crash.

For me, a far more chilling image from Warhol’s “Death and Disaster” series is “Pink Car Crash,” which shows three bloody people flung halfway out of a 1955 Ford that has landed on its roof. One of the two women appears to be alive, but she’s being hugged by a man who’s either unconscious or dead. It doesn’t get much grimmer than this.

Robert Bechtle’s Pontiac

The California-based painter Robert Bechtle makes very different use of automobiles in his hyper-realistic pictures. Rather than making cars into gaudy badges of status or conveyances of disaster and death, Bechtle treats them matter-of-factly as part of the furniture of middle-class American life. He paints everyday scenes without irony or condescension. As he states in the catalog of the inaugural show at the new Whitney Museum of American Art: “My interest in these subjects has nothing to do with satire or social comment. I paint them because they are part of what I know and as such I have an affection for them; I am interested in their commonness and in the challenge of making art from such ordinary fare.”

It’s telling that the above triptych, a self-portrait of the artist and his family on a blandly barbered suburban street, is called “’61 Pontiac.” The painting may give us Mom, Dad, Buddy and Sis, but the beige, no-frills Pontiac station wagon is clearly at the core of this nuclear unit.

Harry Crews’s Ford Maverick

Only Harry Crews would have thought to create a character who sets out to eat a car. His name is Herman Mack, son of the owner of a 43-acre auto junkyard, a true believer in the importance of the automobile. “Everything that’s happened in this goddam country in the last fifty years,” Herman says, “has happened in, on, around, with, or near a car.” And so Herman decides to eat a 1971 Ford Maverick, half a pound a day of blow-torched, swallowable pellets per day, until the car is gone. For good measure – since this 1972 novel, called Car, is a wicked satire of American consumerism – Herman collects the pellets after defecation and melts them down into mini-Mavericks, then sells them as key chains. Herman takes the concept of recycling to a whole new level.

Of course this is all carried on coast-to-coast television because Americans love a spectacle almost as much as they love their automobiles. But for all its conceptual hijinks, this novel, like all of Crews’s fiction, is firmly grounded in the very dirty and bloody real world. His description of a gruesome multi-car smashup is, in the words of one reviewer, “a superb grotesque of the ordinariness of death on the open American road.” Or as one obit writer put it after Crews’s death in 2002, his novels, including Car, out-Gothic Southern Gothic.

E.L. Doctorow’s Model T Ford

When he died on July 21 at the age of 84, E.L. Doctorow was eulogized as a writer who mined American history and historical figures to create a body of fiction that showed, in briskly entertaining fashion, how the past forever informs the present. While The March might be his greatest literary achievement, Doctorow’s most accessible and probably his best-loved novel is 1975’s audacious Ragtime. Michael Chabon recently noted that Doctorow’s blending of historical and fictional characters and his gleeful mining of historical events for fictional purposes provided a “magic way out” for writers caught between an unappetizing choice: dirty realism or arid postmodernism?

When he died on July 21 at the age of 84, E.L. Doctorow was eulogized as a writer who mined American history and historical figures to create a body of fiction that showed, in briskly entertaining fashion, how the past forever informs the present. While The March might be his greatest literary achievement, Doctorow’s most accessible and probably his best-loved novel is 1975’s audacious Ragtime. Michael Chabon recently noted that Doctorow’s blending of historical and fictional characters and his gleeful mining of historical events for fictional purposes provided a “magic way out” for writers caught between an unappetizing choice: dirty realism or arid postmodernism?

At any rate, Ragtime uses a vast canvas to paint a portrait of the twilight of American innocence on the eve of the First World War. It was an age that oozed isms, including patriotism, jingoism, feminism, socialism, hedonism and racism. This big gaudy portrait pivots around a single iteration of what was arguably the most influential invention of the so-called American Century: Henry Ford’s mass-produced Model T. This particular Model T is owned by a Negro musician named Coalhouse Walker Jr. “His car shone,” Doctorow tells us. “The brightwork gleamed. There was a glass windshield and a custom pantasote top.” Coalhouse Walker is terribly proud of his modest automobile, an unimaginable luxury for many black people at that time and, therefore, a scalding affront to many white people. So when a group of racist Irish firefighters desecrate his beloved car, Coalhouse Walker will settle for nothing less than complete justice. His insistence, much like April Wheeler’s confession in the back seat of that ’55 Pontiac, turns out to be a death sentence. Such a big fuss over one of Henry Ford’s affordable little cars!

Denis Johnson’s Oldsmobile

Denis Johnson’s “Car Crash While Hitchhiking” is that rarest thing – a work of fiction you don’t merely read, but experience as if you are inside the story while it’s taking place. Since it’s narrated by a hitchhiker, this short story is, naturally, crowded with cars – a salesman’s “luxury” car, a “VW no more than a bubble of hashish” and, finally, an Oldsmobile with a family inside that performs the story’s central business: it “headonned and killed forever a man driving west out of Bethany, Missouri…”

That “headonned” and “killed forever” hint at Johnson’s verbal wizardry, his ability to write sentences that startle as they sheer off in unexpected directions, creating a sense of disorientation that is crucial to the story’s effect. The hitchhiker passes under “Midwestern clouds like great gray brains.” Here’s the hitchhiker stuck by the side of the road in a downpour: “My thoughts zoomed pitifully. The travelling salesman had fed me pills that made the linings of my veins feel scraped out. I knew every raindrop by its name. I sensed everything before it happened. I knew a certain Oldsmobile would stop for me even before it slowed, and by the sweet voices of the family inside it I knew we’d have an accident in the storm.”

His prediction comes true, of course. Call this what you will: clairvoyance, madness, stoned lunacy. No matter what you call it, it’s great writing. Since the story was first published in the Paris Review in 1989, I’m guessing the deadly Oldsmobile was a mid-’80s model.

Don DeLillo’s Limousine

No one, to my knowledge, has claimed that Cosmopolis is Don DeLillo’s greatest achievement, but this 2003 novel does have an ingenious framing device: it takes place almost entirely inside a white stretch limousine as it conveys the protagonist, a super-rich currency trader named Eric Packer, across Manhattan to get a haircut. Here’s Eric after coming down from his 48-room apartment with its computerized bed, shark tank, gym, screening room and a pen for the borzois:

No one, to my knowledge, has claimed that Cosmopolis is Don DeLillo’s greatest achievement, but this 2003 novel does have an ingenious framing device: it takes place almost entirely inside a white stretch limousine as it conveys the protagonist, a super-rich currency trader named Eric Packer, across Manhattan to get a haircut. Here’s Eric after coming down from his 48-room apartment with its computerized bed, shark tank, gym, screening room and a pen for the borzois:

He put on his sunglasses. Then he walked back across the avenue and approached the lines of white limousines. There were ten cars, five in a curbside row in front of the tower, and five lined up on the cross street, facing west. The cars were identical at a glance.

The limo Eric rides is equipped with an array of visual display units full of financial data, a microwave oven, a heart monitor, a liquor cabinet, a floor made of Carrara marble. This baby puts Gatsby’s Rolls-Royce in the shade, but it’s forced to crawl to its destination, delayed by a presidential motorcade (more limos), a water main break, a political protest, a rap star’s funeral, and various other diversions.

Unfortunately, like so many high-concept ideas, this one sounds better as an elevator pitch than it reads on the page. Straining to sound portentous, these characters come off as gassy. When one of his minions asks Eric why he doesn’t have the barber come to his office, or even to this limo, he replies, “A haircut has what. Associations. Calendar on the wall. Mirrors everywhere. There’s no barber chair here. Nothing swivels but the spycam.”

Nobody talks like this, not even currency traders in danger of losing hundreds of millions of dollars for betting against the yen. But the very worst of this flawed novel’s missteps might be DeLillo’s choice of automobile. A white stretch limo doesn’t spell Master of the Universe; it spells prom night in Poughkeepsie. Cars, it turns out, can kill in more ways than one.