This post is substantially based on a prior project put together by Laura Petelle. We encourage you to visit her Pinterest board hosting the project and her website.

Carel Fabritius’ The Goldfinch, a priceless piece of art has found more fame since the publication of Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch. The actual piece of art The Goldfinch eclipses the other artworks mentioned in the novel, but Tartt’s novel is not just about Fabritius’ painting. The entire art world falls under Tartt’s gaze: criticism, heists, trades, valuations, appreciation. Tartt mentions dozens of paintings, adding depth and richness to her text.

Carel Fabritius’ The Goldfinch, a priceless piece of art has found more fame since the publication of Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch. The actual piece of art The Goldfinch eclipses the other artworks mentioned in the novel, but Tartt’s novel is not just about Fabritius’ painting. The entire art world falls under Tartt’s gaze: criticism, heists, trades, valuations, appreciation. Tartt mentions dozens of paintings, adding depth and richness to her text.

So I present: a definitive list of the artworks in The Goldfinch. (At times, Tartt only provides a loose description, so I have done my best guesswork. Also, when the novel mentions the artist but not the name of the painting, I have chosen the closest example.)

A winter landscape with peasants skating and playing kolf on a frozen river, a town beyond, Pieter Brueghel the Younger, 1621

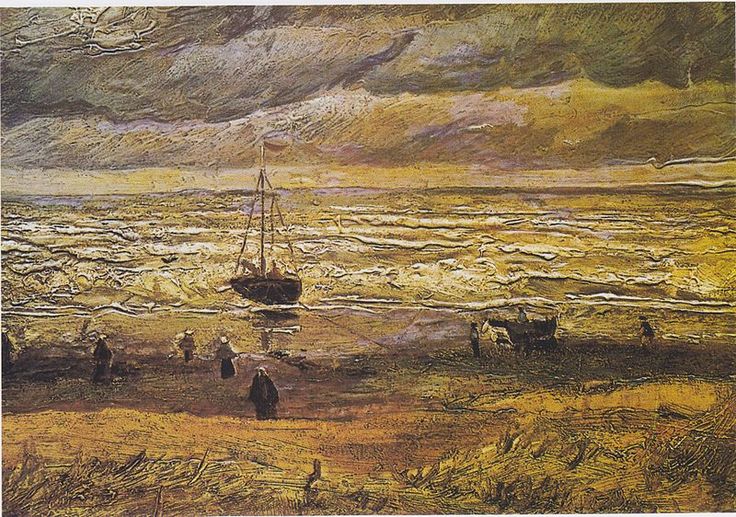

An Estuary with Row and Sail Boats, Jan van Goyen, late 1640

“I spent an unreasonable amount of time scrutinizing a tiny pair of gilt-framed oils hanging over the bureau, one of peasants skating on an ice-pond by a church, the other a sailboat flouncing on a choppy winter sea… I studied them as if they held, encrypted, some key to the secret heart of the old Flemish masters.”

The Jolly Toper, Frans Hals, ca. 1630

Regents of the Old Men’s Almshouse, Frans Hals, 1664

Regentesses of the Old Men’s Almshouse, Frans Hals, 1664

“I hate to race through like this,” she was saying as I caught up with her at the top of the stairs, “but then again it’s the kind of show where you need to come two or three times. There’s The Anatomy Lesson, and we do have to see that, but what I really want to see is one tiny, rare piece by a painter who was Vermeer’s teacher. Greatest Old Master you’ve never heard of. The Frans Hals paintings are a big deal, too. You know Hals, don’t you? The Jolly Toper? And the almshouse governors?”

“Right,” I said tentatively. Of the paintings she’d mentioned, The Anatomy Lesson was the only one I knew. A detail from it was featured on the poster for the exhibition: livid flesh, multiple shades of black, alcoholic-looking surgeons with bloodshot eyes and red noses.

Three Medlars with a Butterfly, Adriaen Coorte, 1705

“I like this one too,” whispered my mother, coming up alongside me at a smallish and particularly haunting still life: a white butterfly against a dark ground, floating over some red fruit. The background—a rich chocolate black—had a complicated warmth suggesting crowded storerooms and history, the passage of time.

“They really knew how to work this edge, the Dutch painters—ripeness sliding into rot. The fruit’s perfect but it won’t last, it’s about to go. And see here especially,” she said, reaching over my shoulder to trace in the air with her finger, “this passage—the butterfly.” The underwing was so powdery and delicate it looked as if the color would smear if she touched it. “How beautifully he plays it. Stillness with a tremble of movement.”

“How long did it take him to paint that?”

My mother, who’d been standing a bit too close, stepped back to regard the painting—oblivious to the gum-chewing security guard whose attention she’d attracted, who was staring fixedly at her back.

“Well, the Dutch invented the microscope,” she said. “They were jewelers, grinders of lenses. They want it all as detailed as possible because even the tiniest things mean something. Whenever you see flies or insects in a still life—a wilted petal, a black spot on the apple—the painter is giving you a secret message. He’s telling you that living things don’t last—it’s all temporary. Death in life. That’s why they’re called natures mortes. Maybe you don’t see it at first with all the beauty and bloom, the little speck of rot. But if you look closer—there it is.”

I leaned down to read the note, printed in discreet letters on the wall, which informed me that the painter—Adriaen Coorte, dates of birth and death uncertain—had been unknown in his own lifetime and his work unrecognized until the 1950s.

Young Man holding a Skull, Frans Hals, 1626-28

The Banquet of the Officers of the St George Militia Company in 1616, Frans Hals, 1616

The Banquet of the Officers of the St Adrian Militia Company in 1627, Frans Hals, 1627

(“Now, Hals. He’s so corny sometimes with all these tipplers and wenches but when he’s on, he’s on. None of this fussiness and precision, he’s working wet-on-wet, slash, slash, it’s all so fast. The faces and hands—rendered really finely, he knows that’s what the eye is drawn to but look at the clothes—so loose—almost sketched. Look how open and modern the brushwork is!”). We spent some time in front of a Hals portrait of a boy holding a skull (“Don’t be mad, Theo, but who do you think he looks like? Somebody”—tugging the back of my hair—“who could use a haircut?”)—and, also, two big Hals portraits of banqueting officers, which she told me were very, very famous and a gigantic influence on Rembrandt. (“Van Gogh loved Hals too. Somewhere, he’s writing about Hals and he says: Frans Hals has no less than twenty-nine shades of black! Or was it twenty-seven?”)

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, Rembrandt, 1632

“Now, Rembrandt,” my mother said. “Everybody always says this painting is about reason and enlightenment, the dawn of scientific inquiry, all that, but to me it’s creepy how polite and formal they are, milling around the slab like a buffet at a cocktail party. Although—” she pointed—“see those two puzzled guys in the back there? They’re not looking at the body—they’re looking at us. You and me. Like they see us standing here in front of them—two people from the future. Startled. ‘What are you doing here?’ Very naturalistic. But then”—she traced the corpse, midair, with her finger—“the body isn’t painted in any very natural way at all, if you look at it. Weird glow coming off it, do you see? Alien autopsy, almost. See how it lights up the faces of the men looking down at it? Like it’s shining with its own light source? He’s painting it with that radioactive quality because he wants to draw our eye to it—make it jump out at us. And here”—she pointed to the flayed hand—“see how he calls attention to it by painting it so big, all out of proportion to the rest of the body? He’s even turned it around so the thumb is on the wrong side, do you see? Well, he didn’t do that by mistake. The skin is off the hand—we see it immediately, something very wrong—but by reversing the thumb he makes it look even more wrong, it registers subliminally even if we can’t put our finger on it, something really out of order, not right. Very clever trick.”

The Goldfinch, Carel Fabritius, 1654

“This is just about the first painting I ever really loved,” my mother was saying. “You’ll never believe it, but it was in a book I used to take out of the library when I was a kid. I used to sit on the floor by my bed and stare at it for hours, completely fascinated—that little guy! And, I mean, actually it’s incredible how much you can learn about a painting by spending a lot of time with a reproduction, even not a very good reproduction. I started off loving the bird, the way you’d love a pet or something, and ended up loving the way he was painted.” She laughed. “The Anatomy Lesson was in the same book actually, but it scared the pants off me. I used to slam the book shut when I opened it to that page by mistake.”

The girl and the old man had come up next to us. Self-consciously, I leaned forward and looked at the painting. It was a small picture, the smallest in the exhibition, and the simplest: a yellow finch, against a plain, pale ground, chained to a perch by its twig of an ankle.

“He was Rembrandt’s pupil, Vermeer’s teacher,” my mother said. “And this one little painting is really the missing link between the two of them—that clear pure daylight, you can see where Vermeer got his quality of light from. Of course, I didn’t know or care about any of that when I was a kid, the historical significance. But it’s there.”

I stepped back, to get a better look. It was a direct and matter-of-fact little creature, with nothing sentimental about it; and something about the neat, compact way it tucked down inside itself—its brightness, its alert watchful expression—made me think of pictures I’d seen of my mother when she was small: a dark-capped finch with steady eyes.

…

“Well, Egbert was Fabritius’s neighbor, he sort of lost his mind after the powder explosion, at least that’s how it looks to me, but Fabritius was killed and his studio was destroyed. Along with almost all his paintings, except this one.” She seemed to be waiting for me to say something, but when I didn’t, she continued: “He was one of the greatest painters of his day, in one of the greatest ages of painting. Very very famous in his time. It’s sad though, because maybe only five or six paintings survived, of all his work. All the rest of it is lost—everything he ever did.”

…

“Anyway, if you ask me,” my mother was saying, “this is the most extraordinary picture in the whole show. Fabritius is making clear something that he discovered all on his own, that no painter in the world knew before him—not even Rembrandt.”

Very softly—so softly I could barely hear her—I heard the girl whisper: “It had to live its whole life like that?”

I’d been wondering the same thing; the shackled foot, the chain was terrible; her grandfather murmured some reply but my mother (who seemed totally unaware of them, even though they were right next to us) stepped back and said: “Such a mysterious picture, so simple. Really tender—invites you to stand close, you know? All those dead pheasants back there and then this little living creature.”

…

“People die, sure,” my mother was saying. “But it’s so heartbreaking and unnecessary how we lose things. From pure carelessness. Fires, wars. The Parthenon, used as a munitions storehouse. I guess that anything we manage to save from history is a miracle.”

View of Delft after the Explosion of 1654, Egbert van der Poel, 1654

The Explosion of the Delft Magazine, Egbert van der Poel, 1654

A View of Delft with the Explosion of 1654, Egbert van der Poel, 1654

“It was a famous tragedy in Dutch history,” my mother was saying. “A huge part of the town was destroyed.”

“What?”

“The disaster at Delft. That killed Fabritius. Did you hear the teacher back there telling the children about it?”

I had. There had been a trio of ghastly landscapes, by a painter named Egbert van der Poel, different views of the same smouldering wasteland: burnt ruined houses, a windmill with tattered sails, crows wheeling in smoky skies. An official looking lady had been explaining loudly to a group of middle-school kids that a gunpowder factory exploded at Delft in the 1600s, that the painter had been so haunted and obsessed by the destruction of his city that he painted it over and over.

Two people stand over the bloody aftermath of the US Civil War battle of Antietam in September, Matthew Brady, 1862

“We had a set of Mathew Brady photographs come through the shop a few years ago — Civil War stuff, so gruesome we had a hard time selling it. … I also knew about Brady’s photographs of the dead at Antietam: I’d seen the pictures online, pin-eyed boys black with blood at the nose and mouth.”

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner: Plate 11: The Death-Fires Danced at Night, Gustave Doré, 1878

When I was a kid—’Rime of the Ancient Mariner,’ those Doré illustrations—no, the ocean gives me the shivers…

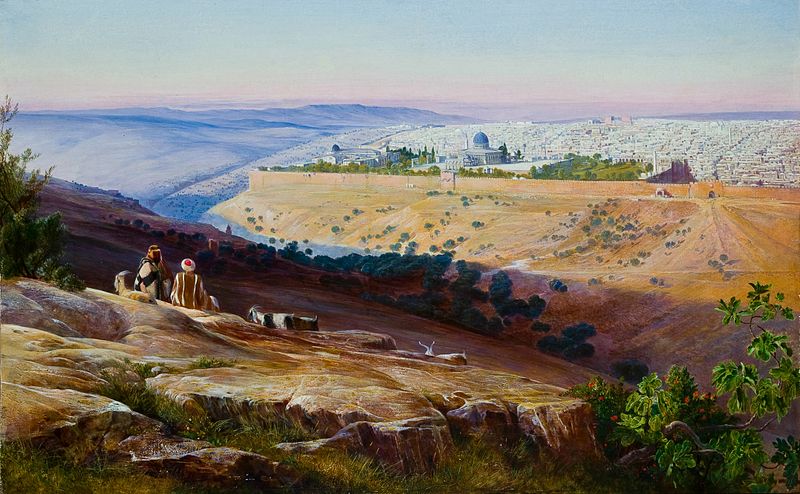

Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives, Edward Lear, 1858-9

“they were across the room fussing over some Edward Lear watercolors”

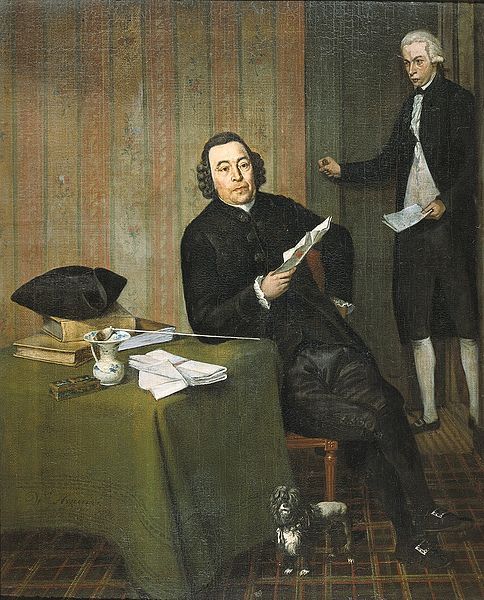

Portret van Cornelis Ploos van Amstel, George van der Mijn, 1758

Wernerus Köhne met zijn knecht Jan Bosch, Wybrand Hendriks, 1787

The Jewish Bride, Rembrandt, 1667

Police, acting on a tip, had recovered three paintings – a George van der Mijn; a Wybrand Hendriks; and a Rembrandt, all missing from the museum since the explosion – from a Bronx home.

Christ washing the feet of his disciples, Rembrandt, 1665

There was a tiny pen-and-brown-ink of Christ washing the feet of St. Peter that was so deftly done (the weary slump and drape of Christ’s back; the blank, complicated sadness on St. Peter’s face) it might have been from Rembrandt’s own hand.

The Aegean Sea, Frederic Edwin Church, 1877

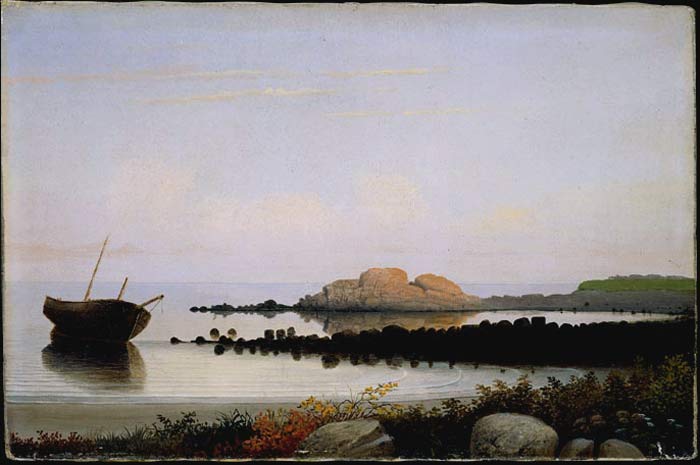

Brace’s Rock, Eastern Point, Gloucester, Fitz Henry Lane, 1864

Still Life with Cake, Raphaelle Peale, ca. 1822

Portrait of Mary Clarke, John Singleton Copley, late 1700s

“when you were a child, I used to catch you in the hallway studying my paintings. You’d always go straight to the best ones. The Frederic Church landscape, my Fitz Henry Lane and my Raphaelle Peale, or the John Singleton Copley — you know, the oval portrait, the tiny one, girl in the bonnet?”

Still Life of Flowers, Fruit, Shells, and Insects by Balthasar van der Ast, 1629, p.498

I’d taken great comfort in the fact that most people assumed that whoever had made off with the van der Asts from Galleries 29 and 30 had stolen my painting, too.

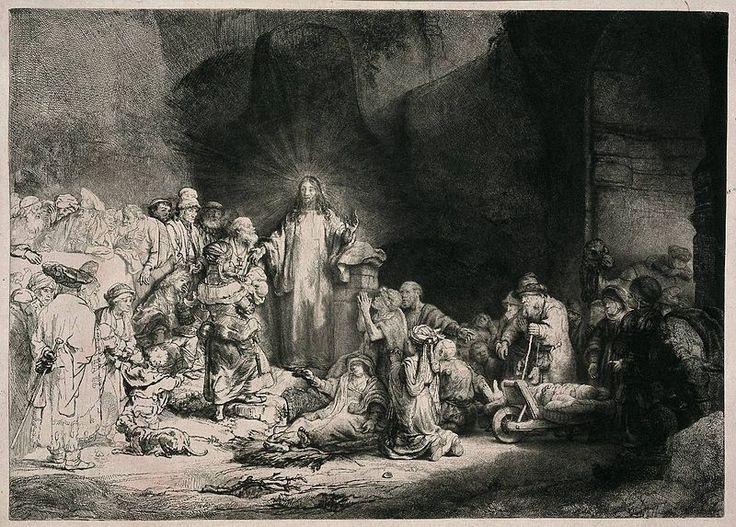

The Hundred Guilder Print, Rembrandt, 1646-50

I knew the work, one of the great stormy drypoints at the Morgan, the Hundred Guilder Print as it was called: the price that Rembrandt himself, according to legend, had been forced to pay to buy it back.

Vanitas, Pieter Claesz, 1625

Italian Landscape with Mountain Plateau, Nicolaes Berchem, 1655

Across the room, I’d noticed several other paintings propped on the wainscoting: a still life, a couple of small landscapes.

“Go look, if you want.” It was Horst. “The Lépine is fake. But the Claesz and the Berchem are for sale if you’re interested.”

Boris laughed and reached for one of Horst’s cigarettes. “He’s not in the market.”

“No?” said Horst genially. “I can give him a good price on the pair. The seller needs to get rid of them.”

I stepped in to look: still life, candle and half-empty wineglass. “Claesz-Heda?”

“No—Pieter. Although—” Horst put the box aside, then stood beside me and lifted the desk lamp on the cord, washing both paintings in a harsh, formal glare—“this bit—” traced mid-air with the curve of a finger—“the reflection of the flame here? and the edge of the table, the drapery? Could almost be Heda on a bad day.”

“Beautiful piece.”

“Yes. Beautiful of its type.” Up close he smelled unwashed and raunchy, with a strong, dusty import-shop odor like the inside of a Chinese box. “A bit prosaic to the modern taste. The classicizing manner.

Much too staged. Still, the Berchem is very good.”

“Lot of fake Berchems out there,” I said neutrally.

“Yes—” the light from the upheld lamp on the landscape painting was bluish, eerie—“but this is lovely… Italy, 1655‥… the ochres beautiful, no? The Claesz not so good I think, very early, though the provenance is impeccable on both. Would be nice to keep them together… they have never been apart, these two. Father and son. Came down together in an old Dutch family, ended up in Austria after the war. Pieter Claesz…” Horst held the light higher. “Claesz was so uneven, honestly. Wonderful technique, wonderful surface, but something a bit off with this one, don’t you agree? The composition doesn’t hold together. Incoherent somehow. Also—” indicating with the flat of his thumb the too-bright shine coming off the canvas: overly varnished.

A Scene on the Ice Near Dordrecht, Jan van Goyen, 1642

I much prefer the van Goyen there. Sadly not for sale.”

“Van Goyen? I would have sworn that was a Corot.”

“From here, yes, you might.” He was pleased at the comparison. “Very similar painters—Vincent himself remarked it—you know that letter? ‘The Corot of the Dutch’? Same tenderness of mist, that openness in fog, do you know what I mean?”

“Where—” I’d been about to ask the typical dealer’s question, where did you get it, before catching myself.

“Marvelous painter. Very prolific. And this is a particularly beautiful example,” he said, with all a collector’s pride. “Many amusing details up close—tiny hunter, barking dog. Also—quite typical—signed on the stern of the boat. Quite charming…

“I must say, I’ve grown so fond of it, I’ll hate to see it go. He dealt paintings himself, van Goyen. A lot of the Dutch masters did. Jan Steen. Vermeer. Rembrandt. But Jan van Goyen—” he smiled—“was like our friend Boris here. A hand in everything. Paintings, real estate, tulip futures.”

White Duck, Jean Baptiste Oudry, 1753, stolen in 1992

Christ in the Storm on the Lake of Galilee, Rembrandt, 1633, stolen in 1990

A Lady and Gentleman in Black, Rembrandt, 1633, stolen in the same heist as the seascape in 1990

Strand von Scheveningen bei stürmischen Wetter, Vincent Van Gogh, 1882, stolen in 2002

“You know what, Theo? Know what? Guess! Guess how lucky we were! Not only do they have your bird in there, but—who would have guessed it? Many other stolen pictures!”

“What?”

“Two dozens, or more! Missing for many years, some of them! And—not all of them are as lovely or beautiful as yours, in fact most of them are not. This is my own personal opinion. But there are big rewards out on four or five of them all the same—bigger than for yours. And even some of the not-so-famous ones—dead duck, boring picture of fat-faced man you don’t know—even these have smaller rewards—fifty thousand, hundred thousand here and there. Who would think? ‘Information leading to recovery of.’ It adds up. And I hope,” he said, with some austerity, “that maybe you can forgive me for that?”“What?”

“Because—they are saying, ‘one of great art recoveries of history.’ And this is the part I hoped would please you—maybe not, who knows, but I hoped. Museum masterworks, returned to public ownership! Stewardship of cultural treasure! Great joy! All the angels are singing! But it would never have happened, if not for you.”

I sat in silent amazement.

…

“Other paintings they recovered. Not just mine.”

“Yes, did you not just hear me say—?”

“What other paintings?”

“Oh, some very celebrated and famous ones! Missing for years!”

“Such as—?”

Boris made an irritated sound. “Oh, I do not know the names, you know not to ask me that. Few modern things—very important and expensive, everyone very excited although I will be frank, I do not understand why the big deal on some of them. Why does it cost so much, a thing like from kindergarten class? ‘Ugly Blob.’ ‘Black Stick with Tangles.’ But then too—multiple works of historic greatness. One was a Rembrandt.”

“Not a seascape?”

“No—people in a dark room. Little bit boring. Nice van Gogh, though, of a sea shore. And then… oh, I don’t know… usual thing, Mary, Jesus, many angels. Some sculptures even. And Asian artworks too. They looked to me worth nothing but I guess they were a lot.”

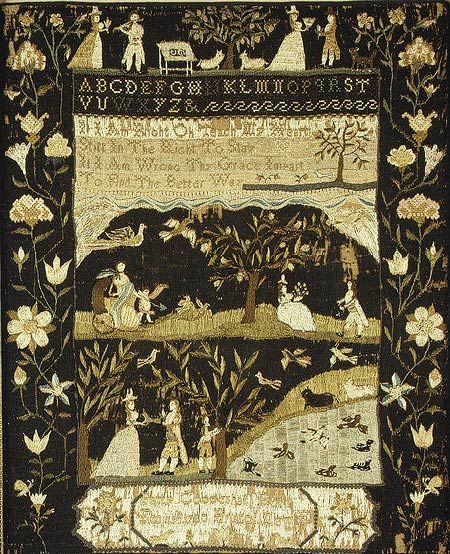

Silk on linen sampler by Martha (Patty) Coggeshall, American, 1780-1797

“Okay,” I said, wondering why he hadn’t mentioned his gift: a child’s needlework sampler, vine-curled alphabet and numerals, stylized farm animals worked in crewel, Marry Sturtevant Her Sample-r Aged 11 1779. Hadn’t he opened it? I’d unearthed it in a box of polyester granny pants at the flea market—not cheap for the flea market, four hundred bucks, but I’d seen comparable pieces sell at Americana auctions for ten times as much. In silence I watched him pottering around the kitchen on autopilot—wandering in circles a bit, opening the refrigerator door, closing it without getting anything out, filling the kettle for tea, and all the time wrapped in his cocoon and refusing to look at me.

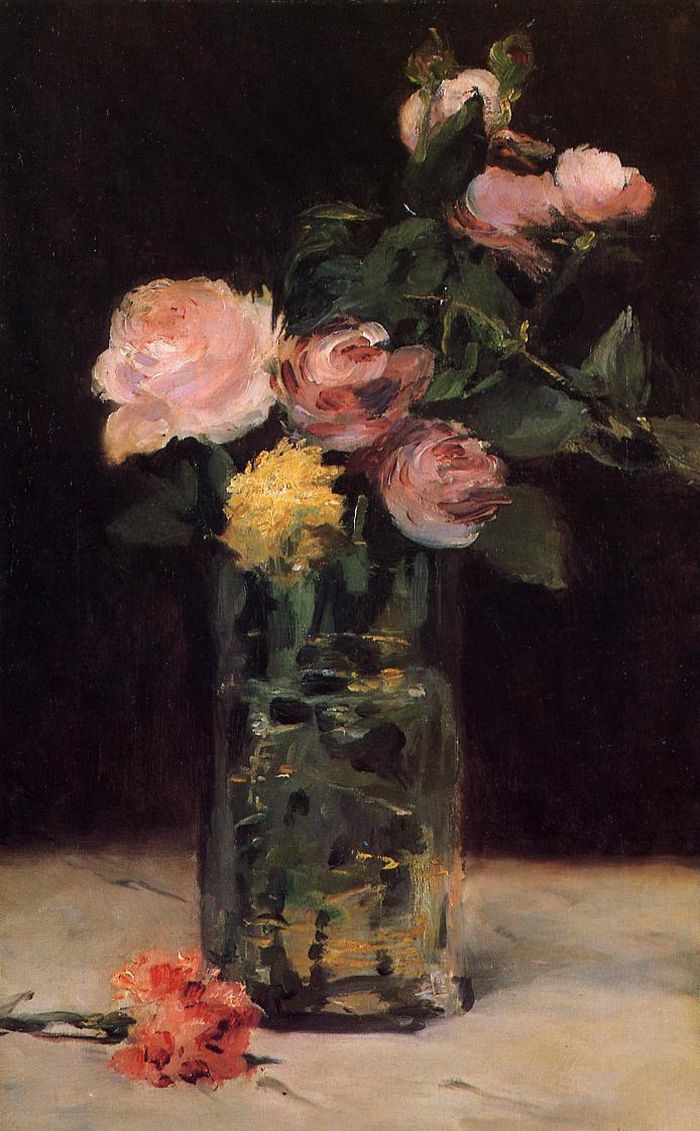

Roses in a Glass Vase, Edouard Manet, 1883

The Trials and Calling of Moses (detail), Sistine Chapel, Botticelli, 1481-1482

“No, no. Wait here. I want to show you something.”

He got up and creaked into the parlor. He was gone a while. And—when he came back—it was with a falling-to-pieces photo album. He sat down. He leafed through it for several pages. And—when he got to a certain page—he pushed it across the table to me. “There,” he said.

Faded snapshot. A tiny, beaky, birdlike boy smiled at a piano in a palmy Belle Époque room: not Parisian, not quite, but Cairene. Twinned jardinières, many French bronzes, many small paintings. One—flowers in a glass—I dimly recognized as a Manet. But my eye tripped and stopped at the twin of a much more familiar image, one or two frames above.

It was, of course, a reproduction. But even in the tarnished old photograph, it glowed in its own isolated and oddly modern light.

“Artist’s copy,” said Hobie. “The Manet too. Nothing special but—” folding his hands on the table—“those paintings were a huge part of his childhood, the happiest part, before he was ill—only child, petted and spoiled by the servants—figs and tangerines and jasmine blossoms on the balcony—he spoke Arabic, as well as French, you knew that, right? And—” Hobie crossed his arms tight, and tapped his lips with a forefinger—“he used to speak of how with very great paintings it’s possible to know them deeply, inhabit them almost, even through copies. Even Proust—there’s a famous passage where Odette opens the door with a cold, she’s sulky, her hair is loose and undone, her skin is patchy, and Swann, who has never cared about her until that moment, falls in love with her because she looks like a Botticelli girl from a slightly damaged fresco. Which Proust himself only knew from a reproduction. He never saw the original, in the Sistine Chapel. But even so—the whole novel is in some ways about that moment. And the damage is part of the attraction, the painting’s blotchy cheeks. Even through a copy Proust was able to re-dream that image, re-shape reality with it, pull something all his own from it into the world. Because—the line of beauty is the line of beauty. It doesn’t matter if it’s been through the Xerox machine a hundred times.”