In one of his essays, the late Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe stated that “no one be fooled by the fact that we write in English, for we intend to do unheard-of things with it.” That “we” is, in essence, an authoritative oratorical posture that cast him as a representative of a group, a kindred of writers who — either by design or fate — have adopted English as the language of literary composition. With these words, it seems that to Achebe the intention to do “unheard-of” things with language is a primary factor in literary creation. He is right. And this should be the most important factor.

Achebe was, however, not merely speaking about the intention of his contemporaries alone, but also of writers who wrote generations before him. Among them would be, ironically, Joseph Conrad, whose prose he sometimes queried, but who embodied that intention to the extent that he was described by Virginia Woolf as one who “had been gifted, so he had schooled himself, and such was his obligation to a strange language wooed characteristically for its Latin qualities rather than its Saxon that it seemed impossible for him to make an ugly or insignificant movement of the pen.” That “we” also includes writers like Vladimir Nabokov of whom John Updike opined: “Nabokov writes prose the way it should be written: ecstatically;” Arundhati Roy; Salman Rushdie; Wole Soyinka; and a host of other writers to whom English was not the only language. The encompassing “we” could also be expanded to include prose stylists whose first language was English like William Faulkner, Shirley Hazzard, Virginia Woolf, William Golding, Ian McEwan, Cormac McCarthy, and all those writers who, in most of their works, float enthusiastically on blasted chariots of prose, and whose literary horses are high on poetic steroids. But these writers, it seems, are the last of a dying breed.

The culture of enforced literary humility, encouraged in many writing workshops and promoted by a rising culture of unobjective literary criticism, is chiefly to blame. It is the melding voice of a crowd that shouts down those who aspire to belong to Achebe’s “we” from their ladder by seeking to enthrone a firm — even regulatory — rule of creative writing. The enthroned style is dished out in the schools under the strict dictum: “Less is more.” Literary critics, on the other hand, do the damage by leveling variations of the accusation of writing “self-conscious (self-important; self-aware…) prose” on writers who attempt to do “unheard-of” things with their prose. The result, by and large, is the crowning of minimalism as the cherished form of writing, and the near rejection of other stylistic considerations. In truth, minimalism has its qualities and suits the works of certain writers like Ernest Hemingway, Raymond Carver, John Cheever, and even, for the most part, Chinua Achebe himself. With it, great writings have been produced, including masterpieces like A Farewell to Arms. But it is its blind adoption in most contemporary novels as the only viable style in the literary universe that must be questioned, if we are to keep the literary culture healthy.

The culture of enforced literary humility, encouraged in many writing workshops and promoted by a rising culture of unobjective literary criticism, is chiefly to blame. It is the melding voice of a crowd that shouts down those who aspire to belong to Achebe’s “we” from their ladder by seeking to enthrone a firm — even regulatory — rule of creative writing. The enthroned style is dished out in the schools under the strict dictum: “Less is more.” Literary critics, on the other hand, do the damage by leveling variations of the accusation of writing “self-conscious (self-important; self-aware…) prose” on writers who attempt to do “unheard-of” things with their prose. The result, by and large, is the crowning of minimalism as the cherished form of writing, and the near rejection of other stylistic considerations. In truth, minimalism has its qualities and suits the works of certain writers like Ernest Hemingway, Raymond Carver, John Cheever, and even, for the most part, Chinua Achebe himself. With it, great writings have been produced, including masterpieces like A Farewell to Arms. But it is its blind adoption in most contemporary novels as the only viable style in the literary universe that must be questioned, if we are to keep the literary culture healthy.

One of the insightful critics still around, Garth Risk Hallberg, describes this phenomenon in his 2012 New York Times Review of A.M Homes’s May We Be Forgiven with these apt observations:

One of the insightful critics still around, Garth Risk Hallberg, describes this phenomenon in his 2012 New York Times Review of A.M Homes’s May We Be Forgiven with these apt observations:

The underlying problem here is style. Homes’s ambitions may have grown in the quarter-century since The Safety of Objects was published, but her default mode of narration remains mired in the minimalism of that era: an uninflected indicative voice that flattens everything it touches. Harry gets some upsetting news: ‘Two days later, the missing girl is found in a garbage bag. Dead. I vomit.’ Harry gets a visitor: ‘Bang. Bang. Bang. A heavy knocking on the door. Tessie barks. The mattress has arrived.’

Hallberg goes on to describe, in the next two paragraphs, the faddist nature of the style:

Style may be, as Truman Capote said, ‘the mirror of an artist’s sensibility,’ but it is also something that develops over time, and in context. When minimalism returned to prominence in the mid-80s, its power was the power to negate. To record yuppie hypocrisies like some sleek new camera was to reveal how scandalous the mundane had become, and how mundane the scandalous. But deadpan cool has long since thinned into a manner. Its reflexive irony is now more or less the house style of late capitalism. (How awesome is that?)

As a non-Western writer, knowing the origin of this fad is comforting. But as Hallberg pointed out, context, not tradition, is what should decide or generate the style of any work of fiction. Paul West noted in his essay, “In Praise of Purple Prose,” written around the heyday of minimalism in 1985, that the “minimalist vogue depends on the premise that only an almost invisible style can be sincere, honest, moving, sensitive and so forth, whereas prose that draws attention to itself by being revved up, ample, intense, incandescent or flamboyant turns its back on something almost holy — the human bond with ordinariness.” This rationale, I dare say, misunderstands what art is and what art is meant to do. The essential work of art is to magnify the ordinary, to make that which is banal glorious through artistic exploration. Thus, fiction must be different from reportage; painting from photography. And this difference should be reflected in the language of the work — in its deliberate constructiveness, its measured adornment of thought, and in the arrangement of representative images, so that the fiction about a known world becomes an elevated vision of that world. That is, the language acts to give the “ordinary” the kind of artistic clarity that is the equivalence of special effects in film. While the special effect can be achieved by manipulating various aspects of the novel such as the structure, voice, setting, and others, the language is the most malleable of all of them. All these can hardly be achieved with sparse, strewn-down prose that mimics silence.

The sinuous texture of language, its snakelike meandering, and eloquent intensity is the only suitable way of telling the multi-dimensional and tragic double Bildungsroman of the “egg-twin” protagonists of Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things. Roy’s narrator, invested with unquestionable powers of insight and deliberative lens, is able to maintain a concentrated force of focus on a very specific instance, scene, or place, or action. Hence, the writer — like a witness of such a scene — is able to move with the sweeping prose that will at once appear gorgeous and at the same time be significant and memorable. Since Nabokov’s slightly senile narrator in Lolita posits that “you can always trust a murderer for a fancy prose style,” we are able to understand why Humbert Humbert would describe his lasped sexual preference for Dolores while in bed with her mum in this way: “And when, by means of pitifully ardent, naively lascivious caresses, she of noble nipple and massive thigh prepared me for the performance of my nightly duty, it was still a nymphet’s scent that in despair I tried to pick up, as I bayed through the undergrowths of dark decaying forests.” Even though the playfulness of Humbert’s elocution is apparent, one cannot deny aptness — and originality — of the description of Humbert’s response to the pleasure his victim is giving him is.

The sinuous texture of language, its snakelike meandering, and eloquent intensity is the only suitable way of telling the multi-dimensional and tragic double Bildungsroman of the “egg-twin” protagonists of Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things. Roy’s narrator, invested with unquestionable powers of insight and deliberative lens, is able to maintain a concentrated force of focus on a very specific instance, scene, or place, or action. Hence, the writer — like a witness of such a scene — is able to move with the sweeping prose that will at once appear gorgeous and at the same time be significant and memorable. Since Nabokov’s slightly senile narrator in Lolita posits that “you can always trust a murderer for a fancy prose style,” we are able to understand why Humbert Humbert would describe his lasped sexual preference for Dolores while in bed with her mum in this way: “And when, by means of pitifully ardent, naively lascivious caresses, she of noble nipple and massive thigh prepared me for the performance of my nightly duty, it was still a nymphet’s scent that in despair I tried to pick up, as I bayed through the undergrowths of dark decaying forests.” Even though the playfulness of Humbert’s elocution is apparent, one cannot deny aptness — and originality — of the description of Humbert’s response to the pleasure his victim is giving him is.

It is not, however, that the “less is more” nugget is wrong, it is that it makes a blanket pronouncement on any writing that tends to make its language artful as taboo. When sentences must be only a few words long, it becomes increasingly difficult to execute the kind of flowery prose that can establish a piece of writing as art. It also establishes a sandcastle logic, which, if prodded, should crash in the face of even the lightest scrutiny. For the truth remains that more can also be more, and that less is often inevitably less. What writers must be conscious of, then, is not long sentences, but the control of flowery prose. As with anything in this world, excess is excess, but inadequate is inadequate. A writer must know when the weight of the words used to describe a scene is bearing down on the scene itself. A writer should develop the measuring tape to know when to describe characters’ thoughts in long sentences and when not to. But a writer, above all, should aim to achieve artistry with language which, like the painter, is the only canvas we have. Writers should realize that the novels that are remembered, that become monuments, would in fact be those which err on the side of audacious prose, that occasionally allow excess rather than those which package a story — no matter how affecting — in inadequate prose.

It is not, however, that the “less is more” nugget is wrong, it is that it makes a blanket pronouncement on any writing that tends to make its language artful as taboo. When sentences must be only a few words long, it becomes increasingly difficult to execute the kind of flowery prose that can establish a piece of writing as art. It also establishes a sandcastle logic, which, if prodded, should crash in the face of even the lightest scrutiny. For the truth remains that more can also be more, and that less is often inevitably less. What writers must be conscious of, then, is not long sentences, but the control of flowery prose. As with anything in this world, excess is excess, but inadequate is inadequate. A writer must know when the weight of the words used to describe a scene is bearing down on the scene itself. A writer should develop the measuring tape to know when to describe characters’ thoughts in long sentences and when not to. But a writer, above all, should aim to achieve artistry with language which, like the painter, is the only canvas we have. Writers should realize that the novels that are remembered, that become monuments, would in fact be those which err on the side of audacious prose, that occasionally allow excess rather than those which package a story — no matter how affecting — in inadequate prose.

In the same vein, describing a writer’s prose as “self-conscious” isn’t wrong, it is that it misallocates blames to an ailing part of a writer’s work. Self-consciousness is a term that mostly describes the metafictional qualities of a work; it cannot, in effect, describe the use of language. “The hand of the writer” can appear in the framing of a story, in its structure, in the characterization, in the form of experimental works and frame narratives, but it cannot appear in its language. “Self-consciousness” cannot be applied to the use of words on the page, just as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart cannot be accused of self-conscious tune or Yinka Shonibare of self-conscious art. Self-consciousness or pomposity cannot be reflected in a piece of writing, except in its tone, and in fiction, this is even harder to detect. What can be reflected in a piece of writing is excess and lack of control, which can stand in the way of anything at all in life. What critics should be calling out should be pretentious, unsuccessful gloss that lacks measure and control. They should call out images that might be inexact, ineffective, or superfluous. When critics plunge head-on against great writers (Don Delilo, Cormac McCarthy, etc.,) in the manner of B.R. Myers’s agitated fracking masquerading as “criticism,” they only end up scaring other writers from attempting to pen artistic prose. Fear might be what many writers writing today seem to be showing by indulging in the writing of seemingly artless prose. Authorial howls of artful prose as created by James Joyce, Faulkner, Nabokov, Cormac McCarthy, Shirley Hazzard, are becoming increasingly rare — sacrificed on the altar of minimalism. Hence, it is becoming more and more difficult to differentiate between literary fiction and the mass market commercial genre pieces, which, more often than not, are couched in plain language.

The gravest danger in conforming to this prevailing norm is that contemporary fiction writers are unknowingly becoming complicit in the ongoing disempowering of language — a phenomenon that the Internet and social media are fueling. Words were once so powerful, so revered, that, as culture critic Sandy Kollick once observed, “to speak the name of something was in fact to invoke its existence, to feel its power as fully present. It was not then as it is now, where a metaphor or a simile merely suggests something else. To identify your totem for a preliterate gatherer-hunters was to be identical with it, and to feel the presence of your clan animal within you.” But no more so. Too many words are being produced in print and visual media that the power of words is diminishing. There are now simply too many newspapers, too many books, too many blogs, too many Twitter accounts for words to maintain their ancestral sacredness. And as writers adjust the language of prose fiction to conform to this era of powerless words, language is disempowered, leading — as Kollick further points out — to the inexorable “emptying out of the human experience,” the very object fiction was meant to preserve in hardbacks and paperbacks.

It is therefore necessary that writers everywhere should see it as their ultimate duty to preserve artfulness of language by couching audacious prose. Our prose should be the Noah’s ark that preserves language in a world that is being apocalyptically flooded with trite and weightless words. “The truest writers,” Derek Walcott said, “are those who see language not as a linguistic process, but as a living element.” By undermining the strongest element of our art, we are becoming unconscious participants in the gradual choking of this “living element,” the life blood of which is language. This we must not do. Rather, we must take a stand in confirmation of the one incontestable truth: that great works of fiction should not only succeed on the strength of their plots or dialogue or character development, but also by the audacity of their prose.

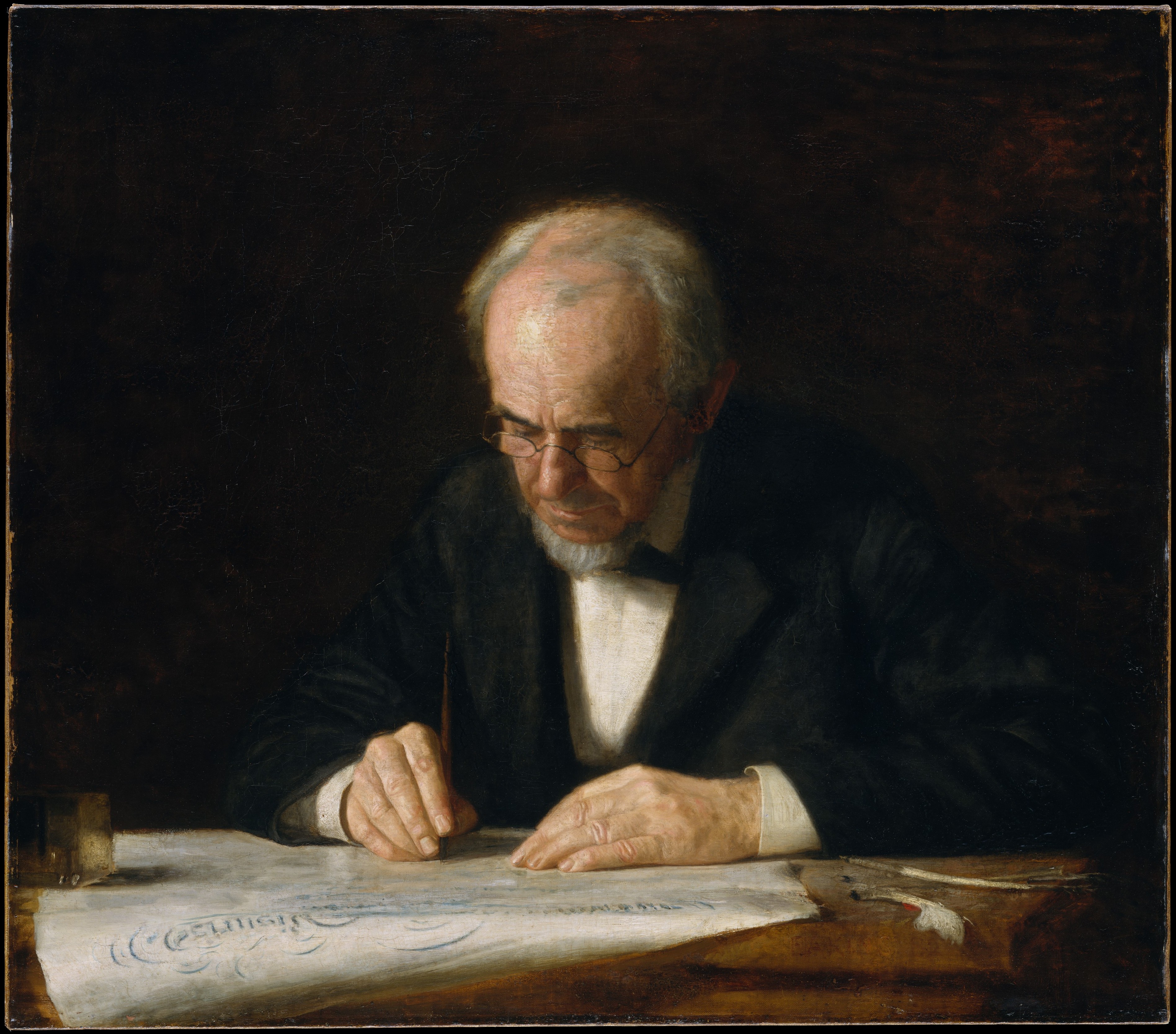

Image Credit: The Met.