A letter appears before the text of The Comedians, the 1966 novel by Graham Greene. The author penned the letter to Alexander Stuart Frere, his longtime publisher who had recently retired. Greene debunks the common assumption that he is the first person narrator of his novels: “in my time I have been considered the murderer of a friend, the jealous lover of a civil servant’s wife, and an obsessive player at roulette. I don’t wish to add to my chameleon nature the characteristics belonging to the cuckolder of a South American diplomat, a possibly illegitimate birth and an education by the Jesuits. Ah, it may be said Brown is a Catholic and so, we know, is Greene…[all characters] are boiled up in the kitchen of the unconscious and emerge unrecognizable even to the cook in most cases.”

A letter appears before the text of The Comedians, the 1966 novel by Graham Greene. The author penned the letter to Alexander Stuart Frere, his longtime publisher who had recently retired. Greene debunks the common assumption that he is the first person narrator of his novels: “in my time I have been considered the murderer of a friend, the jealous lover of a civil servant’s wife, and an obsessive player at roulette. I don’t wish to add to my chameleon nature the characteristics belonging to the cuckolder of a South American diplomat, a possibly illegitimate birth and an education by the Jesuits. Ah, it may be said Brown is a Catholic and so, we know, is Greene…[all characters] are boiled up in the kitchen of the unconscious and emerge unrecognizable even to the cook in most cases.”

Frere, of course, would not need this explanation, so why address the letter to him? Does it instead exist for the edification, or perhaps entertainment, of the reader? Greene’s letter appears without label. Is it an introduction, a preface, a foreword, or something else?

The distinctions between prefaces, introductions, and forewords are tenuous. In the essay “Introductions: A Preface,” Michael Gorra offers a useful introduction to, well, introductions. “An introduction,” he writes, “tells you everything you need to sustain an initial conversation. It might include a bit of biography or a touch of critical history, and it should certainly establish the book in its own time and location, and perhaps place it in ours as well.” Introductions often postdate the original publication of a work. Introductions turn back to move forward a book’s appreciation. Although introductions are often written by someone other than the author, they need not be objective. Gorra thinks the best introductions are “acts of persuasion — ‘See this book my way’ — coherent arguments as learned as a scholarly article but as lightly footnoted as a review.” Although they share a “review’s assertive zest…unlike a review they assume the importance of the work in question.”

Gorra remembers reading introductory essays in used, 1950s-era Modern Library editions as an undergraduate. His understanding of literary criticism was molded by this prefatory form: Robert Penn Warren on Joseph Conrad, Irving Howe on The Bostonians, Angus Wilson on Great Expectations, Randal Jarrell on Rudyard Kipling, Malcolm Cowley on William Faulkner, and Lionel Trilling on Jane Austen. Gorra notes “many of Trilling’s finest essays — pieces on Keats and Dickens and Orwell, on Anna Karenina and The Princess Casamassima — got their start as introductions.”

Gorra remembers reading introductory essays in used, 1950s-era Modern Library editions as an undergraduate. His understanding of literary criticism was molded by this prefatory form: Robert Penn Warren on Joseph Conrad, Irving Howe on The Bostonians, Angus Wilson on Great Expectations, Randal Jarrell on Rudyard Kipling, Malcolm Cowley on William Faulkner, and Lionel Trilling on Jane Austen. Gorra notes “many of Trilling’s finest essays — pieces on Keats and Dickens and Orwell, on Anna Karenina and The Princess Casamassima — got their start as introductions.”

Gorra moves beyond definition to explain the critic’s role within introductions. They need to know “how much or how little information a reader needs to make that book available; he must achieve a critical equipoise, at once accessible but not simplistic.” That care “puts a curb on eccentricity; however strongly voiced, an introduction shouldn’t be too idiosyncratic.” Introductions exist not for the critic, but for the reader. They should be “shrewd rather than clever.” Better to “address the work as a whole” than “approach it with a magic bullet or key or keyhole that claims to explain everything.” The introduction does not unlock the book for its readers; it takes a hand, leads them to the doorstep, and then leaves.

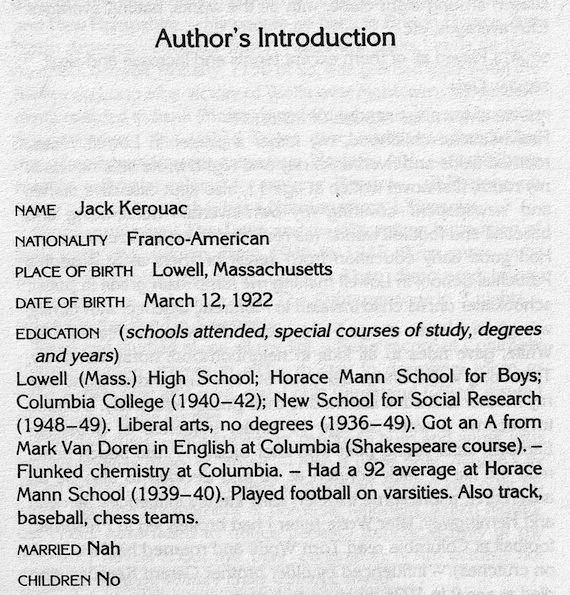

One of the few introductions written by the book’s own author is the unconventional opening to Lonesome Traveler, Jack Kerouac’s essay travelogue. Kerouac formats the essay as a questionnaire.

His response to “Please give a brief resume of your life” traces his childhood as the son of a printer in Lowell, Mass., to his “Final plans: hermitage in the woods, quiet writing of old age, mellow hopes of Paradise.” He shifts from family detail to statements of purpose and misreadings of critics: “Always considered writing my duty on earth. Also the preachment of universal kindness, which hysterical critics have failed to notice beneath frenetic activity of my true-story novels about the ‘beat’ generation. — Am actually not ‘beat’ but strange solitary crazy Catholic mystic.”

Kerouac ends his introduction by replying to the query “Please give a short description of the book, its scope and purpose as you see them” with a nice litany of subjects: “Railroad work, sea work, mysticism, mountain work, lasciviousness, solipsism, self-indulgence, bullfights, drugs, churches, art museums, streets of cities, a mishmash of life as lived by an independent educated penniless rake going anywhere.”

We know Kerouac’s essay is an introduction because he tells us so. It is not a foreword, which, according to The Chicago Manual of Style, is also typically written by someone other than the author. Some dictionary definitions identify a foreword as an introduction. They both introduce, in the sense that they both preface the work. But neither are prefaces — in the traditional sense.

Marjorie E. Skillin and Robert M. Gay’s Words into Type doesn’t differentiate between prefaces and forewords, noting that both consider the “genesis, purpose, limitations, and scope of the book and may include acknowledgments of indebtedness.” Forewords often feel promotional. Skillin and Gay also note that, in terms of numerical pagination, introductions are typically part of the text, while forewords and prefaces have Roman numerals.

My favorite foreword is Walker Percy’s comments on A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole. Percy was teaching at Loyola University in New Orleans in 1976 when “a lady unknown to me” started phoning him: “What she proposed was preposterous…her son, who was dead, had written an entire novel during the early sixties, a big novel, and she wanted me to read it.” Percy was understandably skeptical, but finally gave in, hoping “that I could read a few pages and that they would be bad enough for me, in good conscience, to read no farther.” Instead, he fell in love with the book, especially Ignatius Reilly, “slob extraordinary, a mad Oliver Hardy, a fat Don Quixote, a perverse Thomas Aquinas rolled into one.” Percy essay arrives as a pitch; no one would mistake it for a contemplative preface.

My favorite foreword is Walker Percy’s comments on A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole. Percy was teaching at Loyola University in New Orleans in 1976 when “a lady unknown to me” started phoning him: “What she proposed was preposterous…her son, who was dead, had written an entire novel during the early sixties, a big novel, and she wanted me to read it.” Percy was understandably skeptical, but finally gave in, hoping “that I could read a few pages and that they would be bad enough for me, in good conscience, to read no farther.” Instead, he fell in love with the book, especially Ignatius Reilly, “slob extraordinary, a mad Oliver Hardy, a fat Don Quixote, a perverse Thomas Aquinas rolled into one.” Percy essay arrives as a pitch; no one would mistake it for a contemplative preface.

That last comment admittedly comes from the hip, owing to seduction by sound. Introduction sounds clinical. Foreword sounds, well, you know. Preface massages the ear with that gentle f. Unlike introductions and forewords, prefaces are often written by the authors themselves, and are invaluable autobiographical documents. A preface is an ars poetica for a book, for a literary life. A preface often feels like the writer sitting across the table from the reader, and saying, listen, now I am going to tell you the truth.

In the preface to his second volume of Collected Stories, T.C. Boyle soon becomes contemplative: “To me, a story is an exercise of the imagination — or, as Flannery O’Connor has it, an act of discovery. I don’t know what a story will be until it begins to unfold, the whole coming to me in the act of composition as a kind of waking dream.” For Boyle, imagination and discovery means that he wants “to hear a single resonant bar of truth or mystery or what-if-ness, so I can hum it back and play a riff on it.” He includes memories of middle school, when “Darwin and earth science came tumbling into my consciousness…and I told my mother that I could no longer believe in the Roman Catholic doctrine that had propelled us to church on Sundays for as long as I could remember.” Boyle thinks “I’ve been looking for something to replace [faith] ever since. What have I found? Art and nature, the twin deities that sustained Wordsworth and Whitman and all the others whose experience became too complicated for received faith to contain it.”

In the preface to his second volume of Collected Stories, T.C. Boyle soon becomes contemplative: “To me, a story is an exercise of the imagination — or, as Flannery O’Connor has it, an act of discovery. I don’t know what a story will be until it begins to unfold, the whole coming to me in the act of composition as a kind of waking dream.” For Boyle, imagination and discovery means that he wants “to hear a single resonant bar of truth or mystery or what-if-ness, so I can hum it back and play a riff on it.” He includes memories of middle school, when “Darwin and earth science came tumbling into my consciousness…and I told my mother that I could no longer believe in the Roman Catholic doctrine that had propelled us to church on Sundays for as long as I could remember.” Boyle thinks “I’ve been looking for something to replace [faith] ever since. What have I found? Art and nature, the twin deities that sustained Wordsworth and Whitman and all the others whose experience became too complicated for received faith to contain it.”

By “received faith,” Boyle means a faith prescribed rather than practiced. He later found “the redeeming grace” of O’Connor; his “defining moment” was first reading “A Good Man Is Hard to Find:” “here was the sort of story that subverted expectations, that begin in one mode — situation comedy, familiar from TV — and ended wickedly and deliciously in another.” Boyle’s preface rolls and rolls — think of an acceptance speech that goes on a bit long, but we love the speaker so we shift in our seats and wait out of appreciation.

There are some gems. John Cheever, who taught Boyle at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, “was positively acidic on the subject of my academic pursuits,” but was otherwise “unfailingly kind and generous.” Cheever disliked Boyle’s self-identification as “experimental,” instead insisting “all good fiction was experimental…adducing his own ‘The Death of Justina’ as an example.”

He documents his early magazine submission attempts. He was quite successful, placing early stories in the likes of Esquire and Harper’s, but also had “plenty of rejection.” He covered his bedroom walls with the letters. He ends the preface with a return to first principles: “Money or no, a writer writes. The making of art — the making of stories — is a kind of addiction…You begin with nothing, open yourself up, sweat and worry and bleed, and finally you have something. And once you do, you want to have it all over again.” This act of writing fiction is the “privilege of reviewing the world as it comes to me and transforming it into another form altogether.”

Boyle has already elucidated some of these ideas in an essay, “This Monkey, My Back,” but for other fiction writers, prefaces are rare forays into autobiography. For jester-Catholic Thomas Pynchon, Slow Learner, his sole collection of stories, was his preferred confessional. The essay is labeled an introduction, but I think function trumps form. Pynchon’s essay is self-deprecating, contextual, and comprehensive. It is the closest he has ever come to being a teacher of writing.

Boyle has already elucidated some of these ideas in an essay, “This Monkey, My Back,” but for other fiction writers, prefaces are rare forays into autobiography. For jester-Catholic Thomas Pynchon, Slow Learner, his sole collection of stories, was his preferred confessional. The essay is labeled an introduction, but I think function trumps form. Pynchon’s essay is self-deprecating, contextual, and comprehensive. It is the closest he has ever come to being a teacher of writing.

The last story in the collection, “The Secret Integration,” was written in 1964. Pynchon admits “what a blow to the ego it can be to have to read over anything you wrote 20 years ago, even cancelled checks.” He hopes the stories are cautionary warnings “about some practices which younger writers might prefer to avoid.” Rather than presenting an abstract, sweeping declaration of his amateur past, Pynchon skewers each story in the collection. “The Small Rain,” his first published work, was written while “I was operating on the motto ‘Make it literary,’ a piece of bad advice I made up all by myself and then took.” One sin was his bad dialogue, including a “Louisiana girl talking in Tidewater diphthongs,” indicative of his desire “to show off my ear before I had one.” “Low-lands,” the second piece, “is more of a character sketch than a story,” the narrator of which was “a smart assed-jerk who didn’t know any better, and I apologize for it.” Next up is the infamous “Entropy,” fodder for his second novel, The Crying of Lot 49. Pynchon dismisses the tale as an attempt to force characters and events to conform to a theme. It was overwritten, “too conceptual, too cute and remote.” He looted a 19th-century guidebook to Egypt for “Under the Rose,” resulting in another “ass backwards” attempt to start with abstraction rather than plot and characters. The same “strategy of transfer” doomed “The Secret Integration,” as he culled details from a Federal Writers Project guidebook to the Berkshires.

Pynchon served in the Navy between 1955 and 1957, and notes that one positive of “peacetime service” is its “excellent introduction to the structure of society at large…One makes the amazing discovery that grown adults walking around with college educations, wearing khaki and brass and charged with heavy-duty responsibilities, can in fact be idiots.” His other influences were more literary: Norman Mailer’s “The White Negro.” On the Road by Kerouac. Helen Waddell’s The Wandering Scholars. Norbert Wiener’s The Human Use of Human Beings. To the Finland Station by Edmund Wilson. Niccolo Machiavelli’s The Prince. Hamlet. Our Man in Havana by Graham Greene. Early issues of the Evergreen Review. And jazz, jazz, jazz: “I spent a lot of time in jazz clubs, nursing the two-beer minimum. I put on hornrimmed sunglasses at night. I went to parties in lofts where girls wore strange attire.” The time was post-Beat; “the parade had gone by.”

Pynchon served in the Navy between 1955 and 1957, and notes that one positive of “peacetime service” is its “excellent introduction to the structure of society at large…One makes the amazing discovery that grown adults walking around with college educations, wearing khaki and brass and charged with heavy-duty responsibilities, can in fact be idiots.” His other influences were more literary: Norman Mailer’s “The White Negro.” On the Road by Kerouac. Helen Waddell’s The Wandering Scholars. Norbert Wiener’s The Human Use of Human Beings. To the Finland Station by Edmund Wilson. Niccolo Machiavelli’s The Prince. Hamlet. Our Man in Havana by Graham Greene. Early issues of the Evergreen Review. And jazz, jazz, jazz: “I spent a lot of time in jazz clubs, nursing the two-beer minimum. I put on hornrimmed sunglasses at night. I went to parties in lofts where girls wore strange attire.” The time was post-Beat; “the parade had gone by.”

The essay ends on a note of nostalgia “for the writer who seemed then to be emerging, with his bad habits, dumb theories and occasional moments of productive silence in which he may have begun to get a glimpse of how it was done.” A reader taken with Boyle will forgive his trademark bravado; a reader taken with Pynchon will forgive his self-parodic deprecation. Those who dislike the fiction of either writer won’t stay around for the end of his preface — or crack open the book in the first place.

More often than not, introductory materials are welcomed because we appreciate the fiction that follows. Such expectation can cause problems. The most notable examples are the forewords of Toni Morrison’s Vintage editions, which began with the 1999 version of The Bluest Eye. In “Lobbying the Reader,” Tessa Roynon casts a skeptical eye toward these prefatory remarks. She begins her critique with Morrison’s foreword for Beloved. “Without any apparent self-conscious irony,” Roynon notes, Morrison says she wants her reader “to be kidnapped, thrown ruthlessly into an alien environment as the first step into a shared experience with the book’s population — just as the characters were snatched from one place to another, from any place to any other, without preparation or defense.” This before the reader encounters the first sentence of the actual novel, “124 was spiteful,” which becomes neutered by Morrison’s prefatory, critical self-examination.

More often than not, introductory materials are welcomed because we appreciate the fiction that follows. Such expectation can cause problems. The most notable examples are the forewords of Toni Morrison’s Vintage editions, which began with the 1999 version of The Bluest Eye. In “Lobbying the Reader,” Tessa Roynon casts a skeptical eye toward these prefatory remarks. She begins her critique with Morrison’s foreword for Beloved. “Without any apparent self-conscious irony,” Roynon notes, Morrison says she wants her reader “to be kidnapped, thrown ruthlessly into an alien environment as the first step into a shared experience with the book’s population — just as the characters were snatched from one place to another, from any place to any other, without preparation or defense.” This before the reader encounters the first sentence of the actual novel, “124 was spiteful,” which becomes neutered by Morrison’s prefatory, critical self-examination.

Roynon’s love for Morrison’s fiction is contrasted with her disappointment in the forewords. She considers the essays formulaic and rushed, containing “apparently indisputable interpretations of the text…among profoundly suggestive ambiguities,” as if Morrison is hoarding her own meanings. Roynon worries that Morrison’s goal is the “desire to ensure that readers appreciate the scope of her artistry and her vision to the full.” Shouldn’t that be the experience of her readers? Morrison almost gives them no choice. The essays “demand to be read before the novels they introduce, not least because they are positioned between the dedications/epigraphs and the work’s opening paragraphs.”

Morrison’s prefatory summary for Beloved is so sharp, so commanding that Roynon thinks it threatens to undermine the novel itself: “The heroine would represent the unapologetic acceptance of shame and terror; assume the consequences of choosing infanticide; claim her own freedom.” Morrison has articulated elsewhere her reasons for contributing to the discussion about her books, but the gravity of these forewords makes readers passive recipients. What if the reader experiences the novel slightly differently? Does Morrison’s foreword negate those other readings? As Roynon notes, Morrison’s earlier critical essays would elicit, rather than close, “controversy and discussion.” By focusing on the autobiographical and the contextual, rather than being self-analytical, Morrison’s best forewords treats her readers as participants in the artistic experience, rather than people who are waiting for lectures.

Roynon’s solution is both simple and eloquent:

Were I Morrison’s editor I would urge her to cut the most explicit of her interpretations, to bury the explanations at which we [readers] used to work so hard to arrive. And I would entreat her to move all of her accompanying observations from the beginning of her books to their ends. Turning all the forewords into afterwords would greatly reduce their problematic aspects. In metaphorical terms of which Morrison herself is so fond: we don’t need lobbies or front porches on the homes that she has so painstakingly built. But back gardens? They could work.

No matter whether it is called an introduction, foreword, or preface, the best front piece written by the book’s own author encourages a reader to turn the page and start, but respects her need to experience the work on her own. William Gass’s long preface to In the Heart of the Heart of the Country is an exemplary selection. Originally written in 1976 and revised in 1981, Gass’s preface works as a standalone essay, an inspiring speech for fellow writers, and a document of one artist’s continuing struggle.

No matter whether it is called an introduction, foreword, or preface, the best front piece written by the book’s own author encourages a reader to turn the page and start, but respects her need to experience the work on her own. William Gass’s long preface to In the Heart of the Heart of the Country is an exemplary selection. Originally written in 1976 and revised in 1981, Gass’s preface works as a standalone essay, an inspiring speech for fellow writers, and a document of one artist’s continuing struggle.

Gass reminds us that most stories never get told: “Even when the voice is there, and the tongue is limber as if with liquor or with love, where is that sensitive, admiring, other pair of ears?” His “litters of language” have been called “tales without plot or people.” Received well or not, they are his stories, the words of a boy who moved from North Dakota to Ohio, the son of a bigoted father without “a faith to embrace or an ideology to spurn.” “I won’t be like that,” Gass thought, but “naturally I grew in special hidden ways to be more like that than anyone could possibly imagine, or myself admit.”

Gass turned inward, moved in the direction of words. Lines like “I was forced to form myself from sounds and syllables” sound a bit sentimental if one is somewhat familiar with Gass, but he has always been, in the words of John Gardner, “a sneaky moralist.” Gass began writing stories because “in some dim way I wanted, myself, to have a soul, a special speech, a style…to make a sheet of steel from a flimsy page — something that would not soon weary itself out of shape as everything else I had known.” His earliest stories failed because they were written in the shadow and sound of the canon, leading Gass to wonder “from whose grip was it easier to escape — the graceless hack’s or the artful great’s?”

He broke free “by telling a story to entertain a toothache,” a story with “lots of incident, some excitement, much menace.” That story, the subject of constant revision and reworking for years, would become The Pedersen Kid, his seminal novella. Gass shares his personal “instructions” for the story: “The physical representation must be flowing and a bit repetitious; the dialogue realistic but musical. A ritual effect is needed.” Here one might think Gass is making the same sin of explanation as Morrison, but these are plans, not an exegesis of his work. These thematic plans soon eroded, and “during the actual writing, the management of microsyllables, the alteration of short and long sentences, the emotional integrity of the paragraph, the elevation of the most ordinary diction into some semblance of poetry, became my fanatical concern.” Only years and many rejections later did Gardner publish the story in MSS.

A great preface is a guide for other writers. While the biographical and contextual minutia might be of most interest to aficionados and scholars, working writers who find a great preface are in for a treat. At their best, these introductory essays are the exhales of years of work: years of failure, doubt, and sometimes despair. Gass’s preface for In the Heart of the Heart of the Country contains a handful of gems worthy of being pinned to a cork board above one’s desk:

The material that makes up a story must be placed under terrible compression, but it cannot simply release its meaning like a joke does. It must be epiphanous, yet remain an enigma. Its shortness must have a formal function: the deepening of the understanding, the darkening of the design.

All stories ought to end unsatisfactorily.

Though time may appear to pass within a story, the story itself must seem to have leaked like a blot from a single shake of the pen.

To a reader unhappy with his fiction: “I know which of us will be the greater fool, for your few cents spent on this book are a little loss from a small mistake; think of me and smile: I misspent a life.”

Gass ends with a description of his dream reader. She is “skilled and generous…forgiving of every error.” She is “a lover of lists, a twiddler of lines;” someone “given occasionally to mouthing a word aloud or wanting to read to a companion in a piercing library whisper.” Her “heartbeat alters with the tenses of the verbs.” She “will be a kind of slowpoke on the page, a sipper of sentences, full of reflective pauses.” She will “shadow the page like a palm.” In fact, the reader will “sink into the paper…become the print,” and “blossom on the other side with pleasure and sensation…from the touch of mind, and the love that lasts in language. Yes. Let’s imagine such a being, then. And begin. And then begin.”

A preface might begin as a cathartic act for the writer, but it should end as a love letter to readers. Books are built from sweat and blood, but without the forgiving eyes and hands of readers, books will gather dust on shelves: never touched, never opened, never begun.